Time Travel - Part 1 of 2

Why we can't see the past for what it was and imagine the future for what it could be.

With mini-series, free subscribers receive post previews and have the ability to claim a free essay. Supporters receive the full articles and (re)sources. Thank you for supporting this work.

Part 1 of time travel—Why we can't see the past for what it was and imagine the future for what it could be.

Part 2 of time travel—Literary works clue us into influence and agency of the past; trends and predictions illustrate the difficulty to imagine the future.

As I travel more, I’ve been reflecting upon the nature of time in relation to space.

The excellent Carlo Rovelli talked about it in The Order of Time. From which I surmised that when we see the universe as a series of events, rather than objects interacting with each other, a whole new conception of the world opens up.

Objects are a logical outcome of events and quite possibly so is time—a result of a change of entropy rather than something which passes by objects. This understanding of time is at the center of a widely successful series of books adapted to television.1

Is this spatial movement—aided (or hampered) by memory—what we call ‘time travel’?

If it is, when we move into the past we overlook the very same daily occurrences that seem to mean so much to us today. We travel into the future with a similar forma mentis—a mind set that struggles to imagine new worlds.

What we need in both cases is to step away from our rational selves and into a more undifferentiated dimension. But how can we safely step away from our rituals and customs that keep us rooted to our current place in society and the world?

Reminder: You can get extra insights—in-depth information, ideas, and interviews on the value of culture.

Join the premium list to access new series, topic break-downs, and The Vault.

This conundrum is at the root of much dissatisfaction with life. And the fact that we’re constantly comparing and keeping score doesn’t help. If we are to succeed and bring back value from time travel into the past or the future, our imagination needs fertile ground to till new culture.

Fiction is one such place. I’ve become fascinated with the idea of travel through time when I read Audrey Niffenegger’s The Time Traveler’s Wife.2 The novel is controversial and in parts confusing, but original.

Bare-bones, it’s a story about romance and adventure. Two points of view and experiences switch back and forth between wealthy Clare Anne Abshire and Henry DeTamble, a librarian. He’s the involuntary time-traveler.

Henry is affected by what we later learn is Chrono-Impairment, a rare genetic disorder. Stress is a major factor that makes him jump forward and backward on his life’s timeline. Nothing can go with him into the future or the past.

Imagine the logistics—he arrives naked, and has to find clothing, shelter, and food to survive. It’s akin to how we arrive into the world. But note that, unlike us at birth, he can travel forward and back.

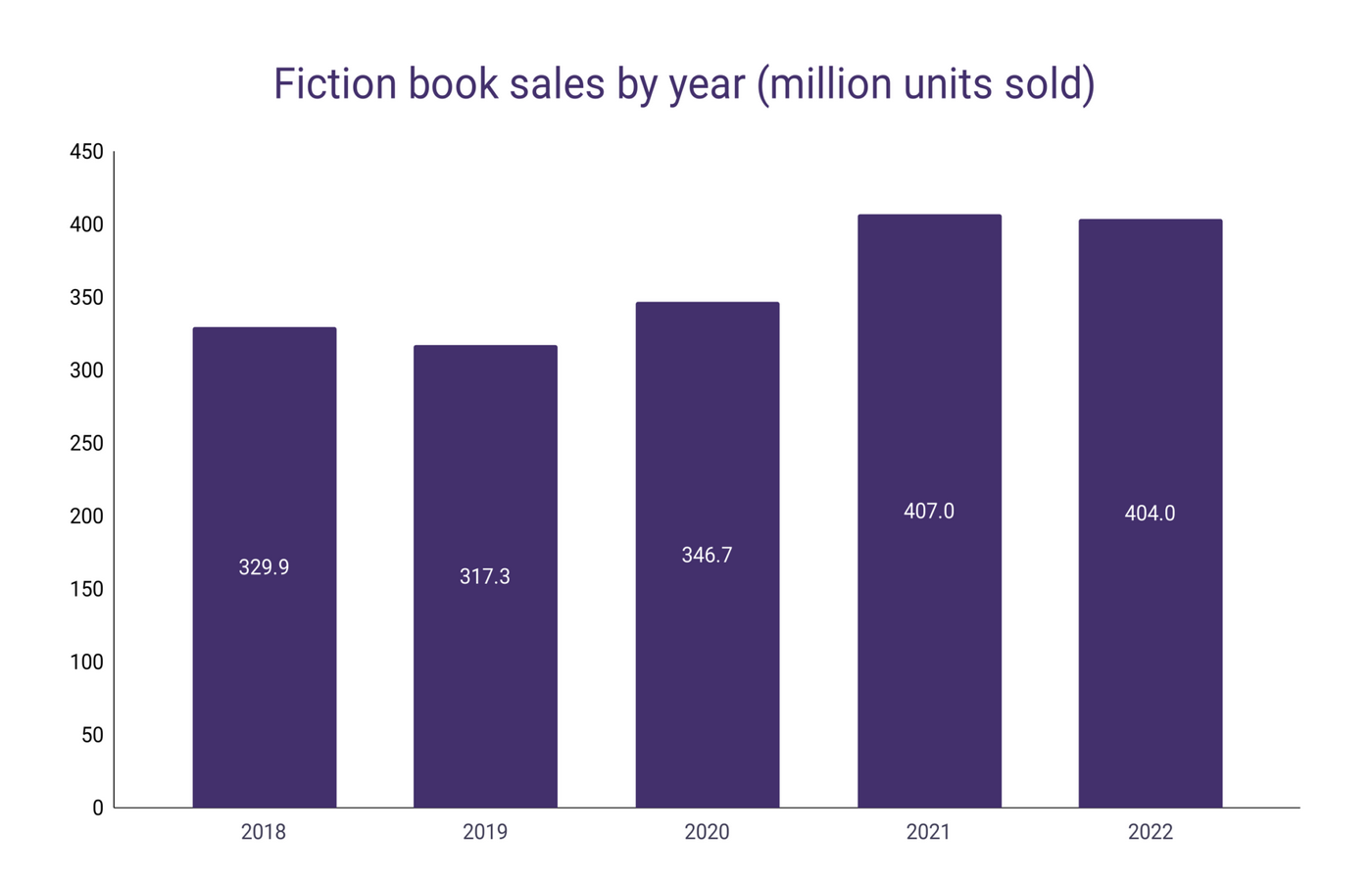

The sci-fi genre deals with the futuristic and imaginative. An there’s a thriving market for business predictions. We don’t seem to get enough of trends and projections. I’m more for historical fiction, but I see the appeal and value of imagining future worlds.

Because where thought and intention go, so do our actions.

Related mini-series: How to read fiction

Part 1 of 4—The cultural value of mystery and historical narrative.

Part 2 of 4—C.S. Harris’ Sebastian St. Cyr novels explore the social tensions, intellectual and creative developments, and political and military events of Regency-era England.

Part 3 of 4—Many layers, depth of characters, valuable dialogue, and beautiful writing—Tana French’s Dublin Murder Squad series.

Part 4 of 4—A sense of place in Louise Penny’s Armand Gamache's Series—Three Pines as a stage and refuge, a sanctuary found by people who are lost.

Many of us would probably like to travel back to happy moments in our lives that didn’t include things like climate change, or to correct major mistakes. We have an idea that a change in the past might impact the future.

Could we act on our knowledge of the future to change the past?

If we had that kind of agency over details of the past, would we try to change outcomes?

That’s one of the themes in Outlander, which begins its chronology in post-war 1945, quickly shifts back by two hundred years—to 1743—and moves forward on both timelines back and forth. Displacement occurs in the beautiful Scottish Highlands.

For example, we learn later that some of the events that seemed inevitable during Clare’s life in the 18th century didn’t happen as she assumed at the time. Was it because of her presence in a time and place that didn’t belong to her?

Her self in 1968 thinks back about what would become the efficient mass murder of the Highlander clans at the Battle of Culloden3 (a destiny she tried to change first in France, then on Scottish soil) by the British, to then discover that her husband Jamie had survived.

A pregnant fellow time-traveler who had been convinced to burn at the stake for witchcraft also mysteriously survives. While Clare had entered the past in 1945, the ‘sorcerer’ did so in 1968—they nearly cross paths during Clare’s visit to Scotland.

To note that Clare’s double life extends to the two marriages—the one to Frank who she admires and respects in present day, and the one she had to make with Jamie to avoid the British gallows.

Luck would have it that Jamie is open-minded, as Clare brings her whole emancipated self to the past. In fact, I found it interesting that society treated women with much more condescension in 1954 Boston than it did in 1745 Scotland. Frank is more concerned about his career than Jamie his life, and Clare would love him more because of it.