How to read fiction - Part 2 of 4

C.S. Harris’ Sebastian St. Cyr novels explore the social tensions, intellectual and creative developments, and political and military events of Regency-era England.

I’ve planned a mini-series for supporters. Free subscribers will continue receiving post previews. Supporters will receive the full articles and (re)sources. Thank you for supporting this work.

If you’re interested in how to read fiction and its cultural value, consider becoming a supporter. This 4-part mini-series will run in the next few weeks.

As we fret over whether artificial intelligence will replace (and/or do away) with us, I’d like to put forth that imagination is the most deeply human faculty. Properly trained and disciplined, imagination can kick ChatGPT’s metal behind any time.

Fiction—in all its forms and genres—is nourishment for our imagination. It’s the fertilizer that helps us make sense of our emotions, sort out our relationships, and understand situations in the real world.

Because though fiction isn’t factual (or data-driven), it’s true.

Most of us know that when we pick up a book and immerse ourselves in its world, we’re the opposite of idle. We face true challenges—whether they’re moral and ethical or emotional—they take us to a truth.

And that’s how we build our knowledge.

Let me ask you something, would you rather imagine the Bubonic Plague from a group of seven young women and three young men who tell each other stories while sheltered in a secluded villa just outside Florence, or from a list of statistics?

In Part 1, I included a brief review of the history and benefits of fiction, and the role of specific genres in culture—with a more detailed outline of the value of mystery/crime and historical fiction in society.

For Part 2, I’m switching more firmly onto the cultural value of historical fiction— with an exploration of C.S. Harris’ Sebastian St. Cyr novels in Regency-era England.

Part 3 is a review of how we brand a market mystery and crime—along with a review of characters and plot in Tana French’s Dublin Murder Squad series.

Finally, in Part 4, I outline the value of place as the context—by analyzing how the characters in Canadian author Louise Penny’s Armand Gamache’s series relate to each other and their environment.

Boccaccio’s Decameron is an incredible document of life at the time (likely 1348.) I found it reassuring that he chose most narrators as women. Prencipe Galeotto was the book’s subtitle.

Boccaccio dedicated the narrative to single women who had no diversions in life. While men had things like hunting, fishing, and falconry, women were forced to conceal their amorous passions and stay idle and concealed in their rooms.

The Decameron inspired another great literary work—Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.

Cultural value of historical fiction

Through literature I learned a great deal about history. The textbook stuff was too filled with names and dates to remember. But give me a good story, and I’ll know the historical circumstances that surrounded it, including the names and dates.

History didn’t just happen in the instant textbooks record. There were people who lived and worked and loved and hoped. There were pain and joy, and mundane things behind decisions and events.

For example, some of the themes the young group discussed in Boccaccio’s Decameron are both a product of the times and timeless. They included:

misfortunes that unexpectedly bring a person to happiness

people who achieve an object of their desire

people who have recovered something previously lost

unhappily and happily ended love stories

tricks lovers play on one another

those who have avoided danger

Historical fiction allows us to step into the minds of the people who came before us. We can see what their world was like, perhaps compare it to ours, but always to imagine what it was like to live like them.

“We write to taste life twice, in the moment and in retrospect.”

Anaïs Nin, essayist and diarist

A lot of research goes into writing a historical novel. The story itself includes many details of the time period, things like social norms, manners, customs, and traditions. The context includes things that really happened and people who were really there.

Popular writers in the historical fiction genre include: Philippa Gregory, Margaret Atwood, Charles Dickens, Leo Tolstoy, Umberto Eco, Jane Austen, Isabel Allende, and Alexander Dumas.

Historical series are cast against the backdrop of history. I recommend reading them in order.

Politics of Regency-era England

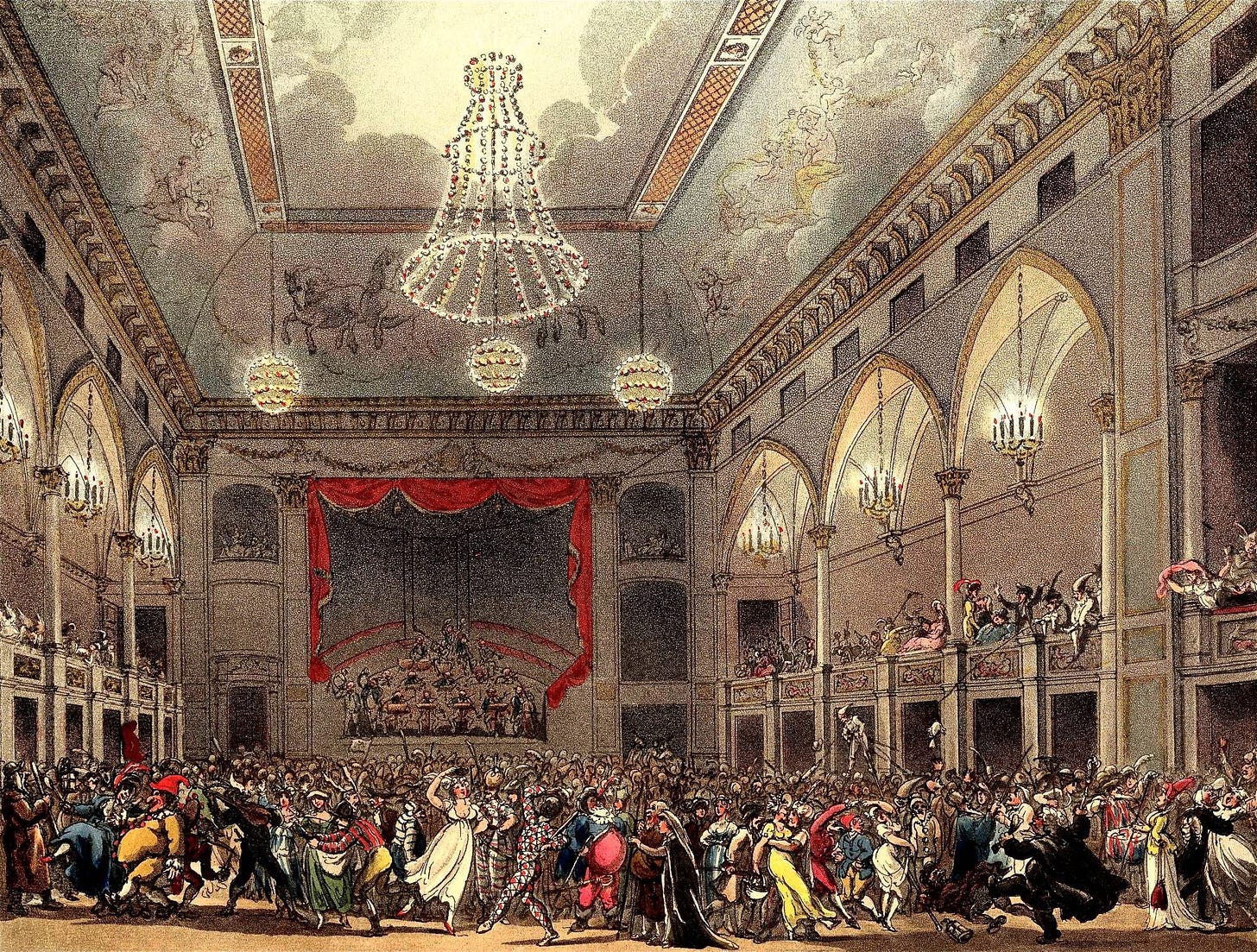

Regency England marked the beginning of Britain’s consolidating its hegemony in Europe and beyond. The French Revolution had come to a close and the Napoleonic wars had just ended. The powers in England were wary of the egalitarian ideas in France spreading to its shores. Hints of this tension are present throughout the series.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On Value in Culture to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.