How to read fiction - Part 3 of 4

Many layers, depth of characters, valuable dialogue, and beautiful writing—Tana French’s Dublin Murder Squad series.

I’ve planned a mini-series for supporters. Free subscribers will continue receiving post previews. Supporters will receive the full articles and (re)sources. Thank you for supporting this work.

If you’re interested in how to read fiction and its cultural value, consider becoming a supporter. This is 4-part mini-series.

I love the puzzles I find in mystery fiction. They draw me in one clue at a time, until I suspend belief to see what happens. Human beings are the most extraordinary mystery of all. How we work, but also, what makes us who we are.

There’s a wonderful, generous, expansive side to a person. The friend, the confidant, the comrade, the mate, the partner, the person who’s got your back. They’re the one who takes your call, whose shoulder you can cry on, the listener who doesn’t judge.

There’s also a frightening part.

We’re inscrutable to others. When we become mysterious to ourselves, we could be in for a wonderful adventure of discovery. We’re capable of so much more. For the same reason we could also be terrifying. The manipulator, the detractor, the delusional.

Time and again, we’re caught in the tensions between order and chaos, detachment and empathy, fast and slow, thoughtful and thoughtless, love and hate. In the grip of our daily pressures the smallest thing could take a life of its own.

Compelling writers notice the little things and imagine the ‘what ifs.’ They’re archeologists of human nature—they brush away the clay all the way to the bone. And there we are, bare at last.

“I have always been caught by the pull of the unremarkable, by the easily missed, infinitely nourishing beauty of the mundane.”

Tana French, interview

Perhaps that’s why the crime novel—more than any other genre—has become the social document of our time. Murder is as old as humankind, but just when the plot thickens, we’ve lost patience with solutions that are not immediate.

I should know. I’ve been writing about topics that don’t have an easy answer for nearly eighteen years. I notice people are dismissive of things that don’t fit into simple explanations—less and less willing to put in the time and thought.

Yet crime has a complex genesis. One that requires patience and willingness to delve into the past, to sift through the mundane, to stay with the details and the boring, to confront resistance and find dissonance.

The ‘charge, indictment, accusation’ (Latin crimen, genitive criminis) generally comes after the ‘crime, fault, offense,’ yet they’re both at root of the word crime. Over the centuries, no doubt due to the influence of the Church, the idea of sin came into it.

Old French crimne associated crime with ‘mortal sin’ (12th C.) We went through ‘sinfulness, infraction of the laws of God’ (13th C) before we got to ‘offense punishable by law, act or omission which the law punishes in the name of the state’ in the late 14th C.

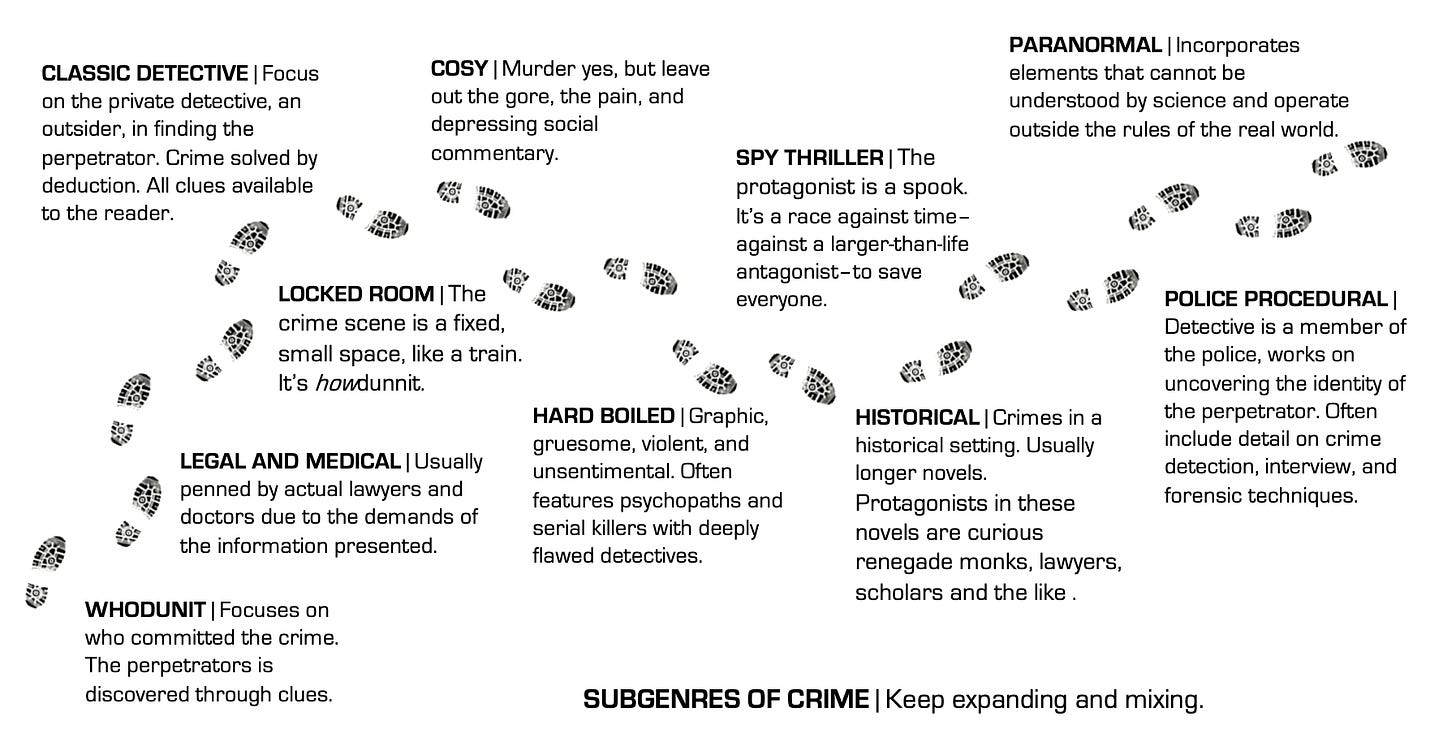

Mystery crime is a strong preference for readers of fiction in most sub-genres. However, the lines are starting to blur between them. There’s even a hint of genres blending—like mystery and science fiction.

In Part 1, I included a brief review of the history and benefits of fiction, and the role of specific genres in culture—with a more detailed outline of the value of mystery/crime and historical fiction in society.

For Part 2, I switched more firmly onto the cultural value of historical fiction—with an exploration of C.S. Harris’ Sebastian St. Cyr novels in Regency-era England.

Part 3 is a review of how we brand a market mystery and crime—along with a review of characters and plot in Tana French’s Dublin Murder Squad series.

Finally, in Part 4, I outline the value of place as the context—by analyzing how the characters in Canadian author Louise Penny’s Armand Gamache’s series relate to each other and their environment.

The blending of sub-genres an interesting challenge for agents and publishers who have a specific focus. How do you design the cover to appeal to readers of both genres? Branding and marketing are often as (if not more) important than the writing.

If only all good writers could find their readers!

You and I know that’s not the case. Discovery is still a big question mark. And because people have only so many hours in a day, it’s very much left to ‘best of’ and books everyone’s talking about. Good old public relations has a big role in the promotion of fiction works.

We’re more distracted and busier than ever. Visual appeal is critical for a book to stand out.

Books and their covers

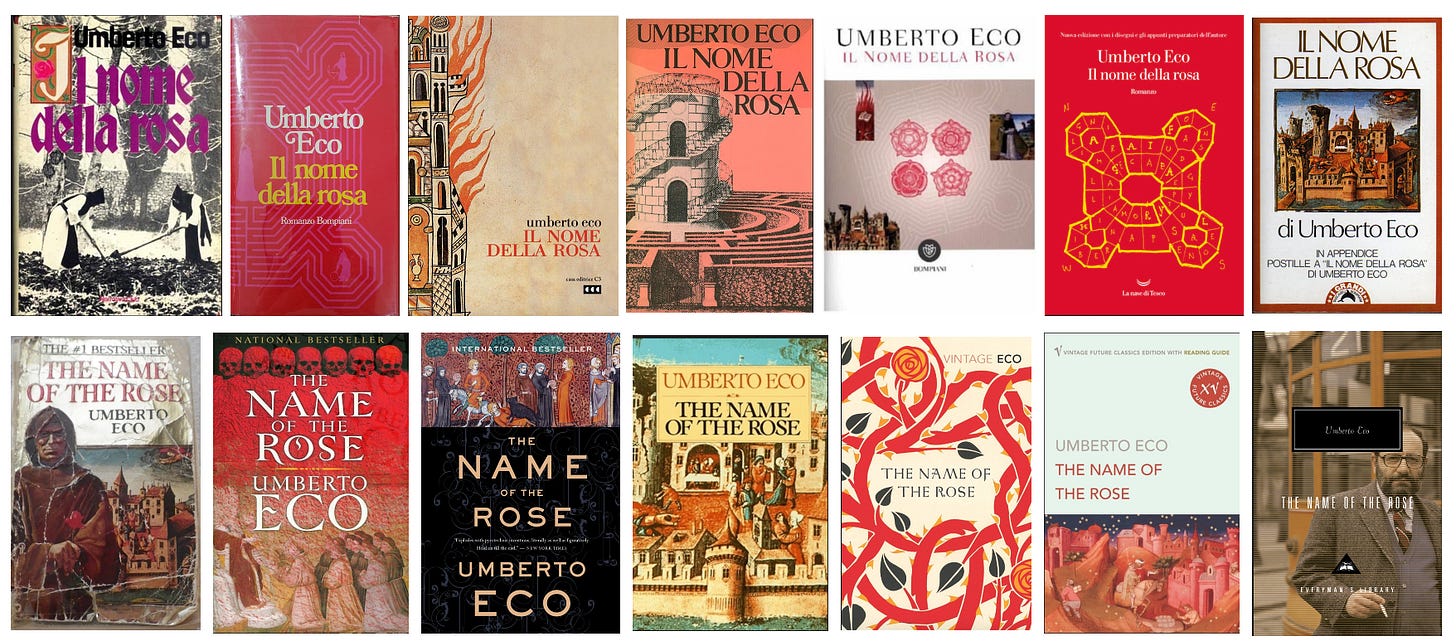

We’ve seen good examples of covers for historical mysteries in Part 2 of this four-part series with C.S. Harris. Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose is in this category. Hardboiled and detective crime feature symbolic images and typeface.

Hardbacks and paperbacks have different covers. The cover designs for international editions are based on cultural interpretations. Australia, England, and America have different covers, in case you were wondering. Separated by the same language.

Cozy mysteries may have an animal or a group of people on the cover. Lilian Jackson Braun’s The Cat Who Mysteries feature Jim Qwilleran and his sleuthing cat Koko, and Laura Childs’ A Tea Shop Mystery series are two examples.

Procedural crime mysteries feature places or symbols on the cover. The story angle is based on the protagonist’s skills—Jeffery Deaver’s Lincoln Rhyme is a forensic consultant, Kathy Reichs’ Temperance Brennan is a forensic anthropologist, Ian Rankin’s John Rebus is a detective.

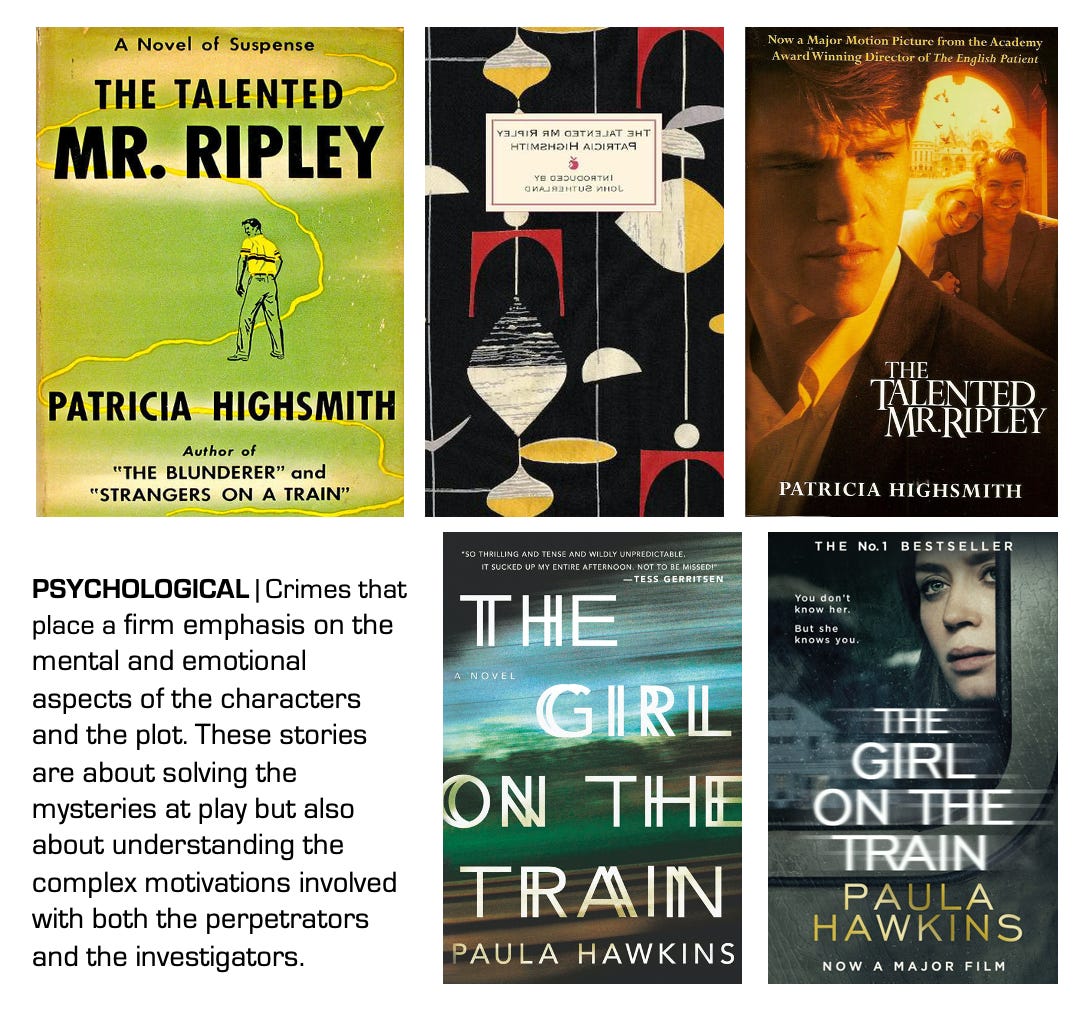

Psychological crime thrillers feature people and places. Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley cover had different designs over the years. Eventually, it featured Matt Damon from the film. Paula Hawkins’ The Girl On The Train featured the blurred landscape, then the film’s protagonist.

While fewer people enjoy sitting down with a procedural book, you can see the growing popularity of psychological crime mysteries. Tana French blends the two. To get her stories straight, she has long conversations with a retired detective.

“He’s a really lovely man, a genuinely sound guy who’s been so generous with his time and so friendly. And he turned on a dime. Suddenly he was this unstoppable force. I’m not talking mean, I’m not talking aggressive. Just unstoppable. He was coming for some information and nothing was going to stop him. Nothing.”

[…]

“But you have no idea. You’ve never practiced being interviewed by a detective. And suddenly you’re in somebody else’s world and in somebody else’s hands. That’s a very different experience, even just a five-minute-phone-call hypothetical [interrogation]. And that stuck with me, what would that feel like.”

Tana French, interview

Her books are long, the plots complex. Passionate followers enjoy both. The characters and relationships in the novels ask a lot of readers. Tana French doesn’t write typical mystery and crime books. They’re more literary thrillers.

Yet more than 5 million people have made the Dublin Squad Murders bestsellers.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On Value in Culture with Valeria Maltoni to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.