How to read fiction - Part 1 of 4

The cultural value of mystery and historical narrative.

I’ve planned a mini-series for supporters. Free subscribers will continue receiving post previews. Supporters will receive the full articles and (re)sources. Thank you for supporting this work.

If you’re interested in how to read fiction and its cultural value, consider becoming a supporter. This 4-part mini-series will run in the next few weeks.

I read a lot of fiction, always have since I started to read. We all read fantasy books as children, our parents read them to us. Pinocchio was a favorite. Published in Il Giornale per Bambini, the first Italian publication for children, between 1880-1881, the moral tale is a good read for children and adults.

Then I graduated to mystery and crime books as a teenager. I kept Agatha Christie’s1 Hercule Poirot series for the beach. It was the perfect companion to lazy summer days under the shade surrounded by sand; the sounds of other people receded.

Literary fiction was must-read in school, a staple of my education—from elementary all the way to University. Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio, then Chaucer, Auden, James, Eliot, Shakespeare, Hesse, Stendhal, Proust and many more.

Throughout our younger years, we read quite a lot of stories for pleasure and/or duty. But then we fall out of reading fiction. It’s a mistake we make, because somehow we think fiction is not for leaders.

Humans have used books, poetry and other written words as a form of therapy for centuries. We yearn for believable worlds that at least feel realistic even if they aren’t. That’s why we read fiction.

I promised I’d write more about books. And I cannot think of a more valuable topic than fiction for our first four-part series of the year.

But first, a short poll with an incomplete list of genres to get you thinking about how we group fictional stories. There are between 35 and 50 main genres, and potentially even more, depending on who you ask. Most stories fit into a genre.

Yet, most books are a mix of genres. The Iliad, is a fantastic, long form, arch-plot liteary story with war as the plot for education. Publishers and book critics look at it this way.

Readers pick it up either because they have to for school, or want to for themselves. We read fiction because we enjoy it. But it also increases social acuity and improves our ability to understand other people’s motivations.

We develop empathy—a far more elusive goal. Fiction is the ultimate multitasker.

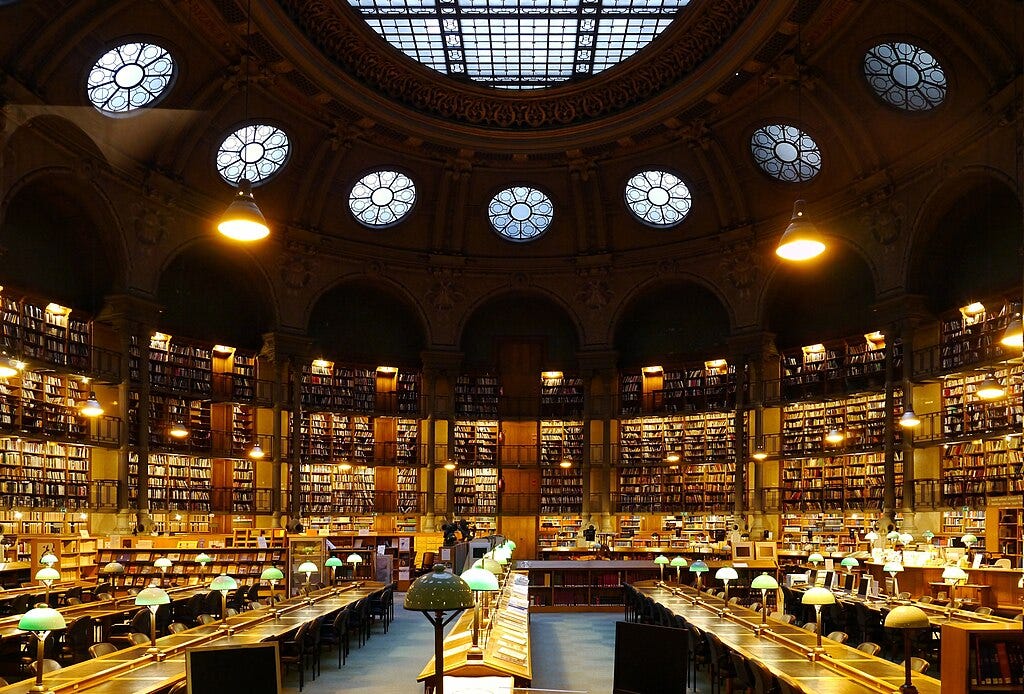

Our stories have transmitted culture from one generation to another, an era to the next. Before we had the written form, our memory did the hard work. With the written word, libraries had a vital role in the storage and transmission of culture.

While all genres help, I’ve picked the two I read both because I’m most familiar with them, and because I believe they work the hardest as a social document.

In Part 1, I’m including a brief review of the history and benefits of fiction, and the role of specific genres in culture—with a more detailed outline of the value of mystery/crime and historical fiction in society.

Then, in Part 2, I’ll switch more firmly onto the cultural value of historical fiction— with an exploration of C.S. Harris’ Sebastian St. Cyr novels in Regency-era England.

Part 3 is a review of how we brand a market mystery and crime—along with a review of characters and plot in Tana French’s Dublin Murder Squad series.

Finally, in Part 4, I outline the value of place as the context—by analyzing how the characters in Canadian author Louise Penny’s Armand Gamache’s series relate to each other and their environment.

Access to inner structure of society

While stories are as old as humankind—myths, epic poetry of heroes and monsters, fables and songs—fiction is a specific kind of storytelling. It emerged in 12th century England as an offshoot of a multilingual literary culture.

In a technical sense, fiction is a mode of writing in which both writer and reader know that what’s described cannot have happened. They each know, and know that the other knows. This is an important contract.

Fiction is about the unknowable. The account is not verifiable. However, it doesn’t mean that the account cannot be set in the author’s world and follow all the rules of that world.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On Value in Culture with Valeria Maltoni to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.