The ‘published’ series is a regular roundup of links and thoughts for all with a wrap on the theme and additional notes for paid supporters. I plan to turn this into an open thread and ongoing Ask Me Anything in the comments.

She’s the Greek goddess of the soul—Ψυχή, which means life, Latin prefix ‘psych’—a beautiful woman with butterfly wings. Once a mortal princess of extraordinary beauty, she turned heads.1

Psyche is the word for the 2024 festivalfilosofia. For three days, the philosophy festival changes the face of the cities of Modena, Carpi and Sassuolo by setting up open, common and widespread spaces for learning and conversation.

Fifty master classes by protagonists of the Italian and international cultural scene articulate a key word. The word at each edition refers to fundamental questions of philosophical discussion and crucial experiences of the contemporary condition.

The creative program is broad and includes exhibitions and installations, live performances and concerts, games and workshops, films and philosophical dinners. All designed to highlight the virtuous connections between the forms of reflection and those of artistic creation.

Squares and courtyards, historic centers and monumental sites return to their old role of places to listen and participate—where residents and visitors can share access to knowledge and situations of dense relationships.

A trade of ideas, which builds social energy.

The cities as a whole contribute to the success of the event. Not only the cultural partners— museums and galleries, libraries and associations—but also post offices and businesses, restaurants, hotels, and the volunteers are all part of the project.

Admission is free to all the events in the program, including lectures and exhibitions. I cannot think of a more inclusive initiative. One that energizes the entire population in mid-September, just as students get ready to go back to school.

This week’s round up of culture is related to some of the main themes of this year’s festival.

On Value in Culture is a guide to the role of narrative, language, and art in how we organize, perceive, and communicate about reality. To support my work, take out a paid subscription.

1/8 Since the last round-up, On Value in Culture published:

The Greatest Speech—In 431 BC, the Athenian statesman Pericles delivered one of the most influential speeches of all time—a funeral oration.

(🔒) On the Value of Unread Books—“Books are not made to be believed, but to be subjected to inquiry. When we consider a book, we mustn't ask ourselves what it says but what it means.” Umberto Eco

August 15—On the value of dates.

(🔒) The Most Important Speech—You can kill a person, but you cannot kill an idea. Especially when that idea means freedom.

Deep Truths—Why isn’t the tech industry regulated? And other things you've always wanted to know.

(🔒) Cinema Rediscovered—Five films that capture the zeitgeist of their times.

To Think Different, Read Different—Take the most subscribed ‘Substacks’ on culture—they feel like a version of the same popular topics.

(🔒) The Face of Heroism—Ancient Greece had two heroes—Odysseus and Achilles. Greek culture had a preference, and so does ours.

A reminder for supporters that they can access full articles and commentary at The Vault (🔒). Thank you for supporting my work on value.

2/8 Though sometimes it’s hard to see it, there’s a place for everyone. It just may not be the physical place where you are. We’re creative machines, humans have a drive to express talent. Yet so much of the current narrative discourages us.

Amidst abundance, there’s scarcity of hits. When social networks first emerged, we were supposed to have more channels for opportunity. The long tail never happened, or did it? I found Adam Mastroianni’s essay uplifting.

“The globalization of attention is a damn shame for many reasons, and the biggest is that it leaves lots of local niches neglected. If everyone’s trying to be an Instagram relationship advice influencer, nobody’s trying to be their friendly neighborhood Breakup Whisperer. Plus, everybody, no matter how much of a nobody they are, has at least a few people who are counting on them, whose lives they can ruin or enrich, and it’s hard to do much enriching when you’re fretting full-time about who’s gonna be the next president.

Local niches are important because they can pack a lot of meaning into a tiny space; they make it so that more people can matter.”

Instead, what happened with social, is that networks became media and hits turned to be the same on every channel. Winners take all. Have we forgotten about in person presence?

Places have a local component and there bodies are ‘somebody.’

3/8 Our ancestors knew that art is one of our gateways to the divine—and that’s brought in starker relief by the exquisite marble statues we can still admire today. Culture about representations of Mary and Muhammad shifted over the ages.

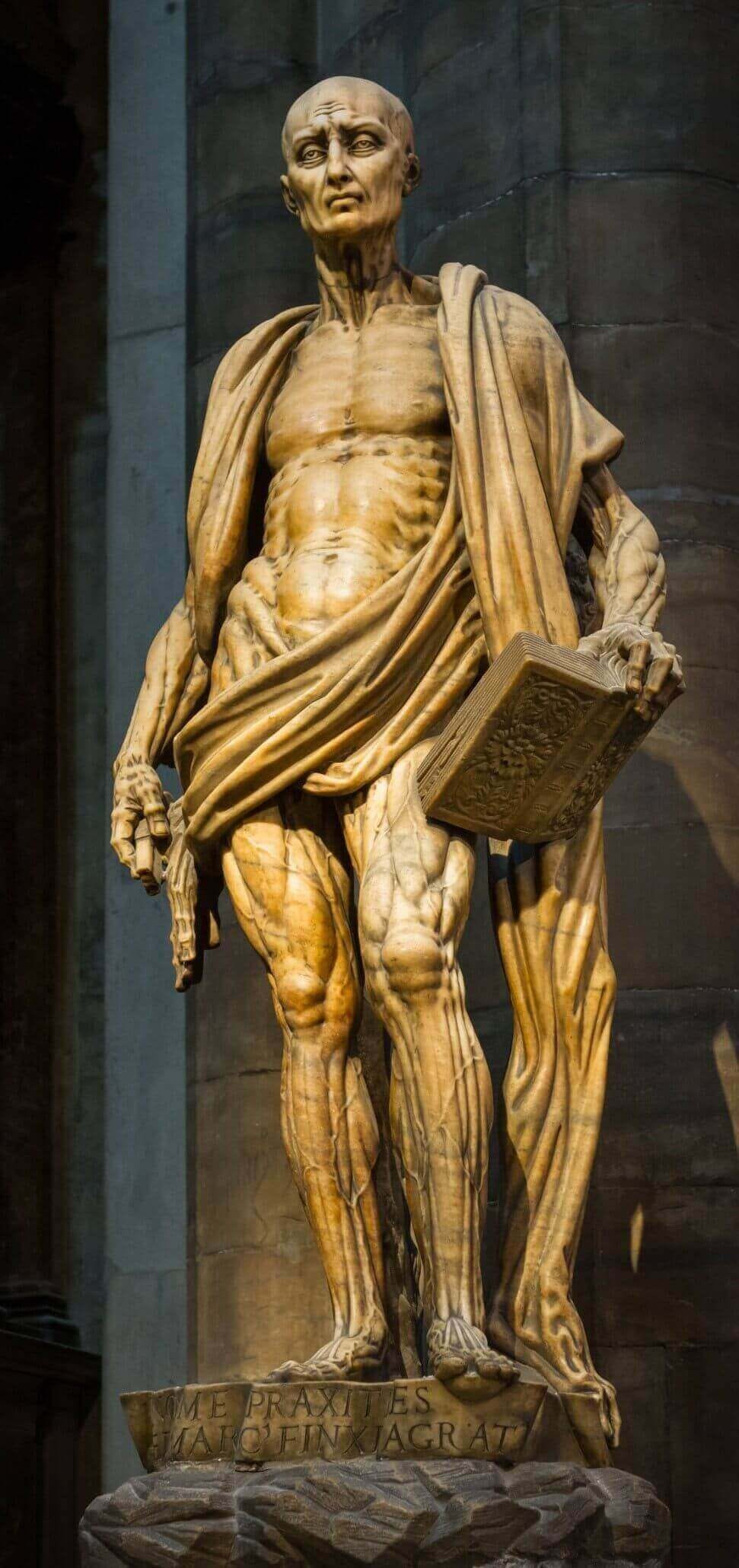

More than 3,500 statues adorn the Duomo in Milano. They represent images from everyday life, but also hidden surprises. But the most impressive piece of art is the stunning statue of Saint Bartholomew, which. you can find inside the church.

“As punishment for converting the king of Armenia to Christianity, Bartholomew was martyred by being skinned alive. To depict this, Renaissance sculptor Marco d’Agrate produced a rare example of an écorché (a figure showing the muscles of the body without skin) in marble. His incredible anatomical precision makes it all the more haunting.

Yet true to the spirit of martyrdom, Saint Bartholomew is not shown as a man in the painful throes of death. He instead stands brave, defiant, and resilient in the face of tribulation.

Bartholomew proudly wears his own skin like a ‘cloak,’ draped over him in regal, senatorial fashion. In his hand he clutches the knife that flayed him — the weapon wielded against him is made powerless. According to legend, Bartholomew continued preaching to a rapt audience after his executors had flayed him.”

Check out the anatomy and by the emphasis on the martyr’s body, without skin, which is draped over him as a tunic. The macabre detail represents the fisherman Bartholomew, one of Christ’s Apostles.

Earthly torture contrasts divine ecstasy—and is a testimony to the endurance of faith.

Lombard sculptor Marco d’Agrate sculpted the statue in 1562.

4/8 Fairy tales are the places where humans first measure themselves with the strange and unordered. Charles Dickens thought them they’re critical to our growth and development. And with good reasons.

“It is very important to Dickens that fairy tales be preserved and transmitted in all their strangeness, all their oddity, and in everything that might offend. The practice of editing fairy tales to make them more pleasing to the Modern Sensibility appalls him.”

Dickens himself transmits some of the virtues we absorb when we read. If we still read.

“Forbearance, courtesy, consideration for poor and aged, kind treatment of animals, love of nature, abhorrence of tyranny and brute force.”

5/8 Rory Sutherland is the master of reframing—he reveals how we can see things differently just with a simple change of reference. We’re not used to grand narratives anymore. Instead, we labor in small tweaks.

But if we did grasp the role narrative, language, and art play in how we organize, perceive, and communicate about reality (my mantra with this project) we could and would be able to do the work of change. Because people and ideas are prime movers.

Which comes to bear as we question the bias toward speed humanity has developed. How we design everything is how we end up living it. And right now, it seems that faster is better. Is it, though?

Why have we allowed the urgent to drown out the important?

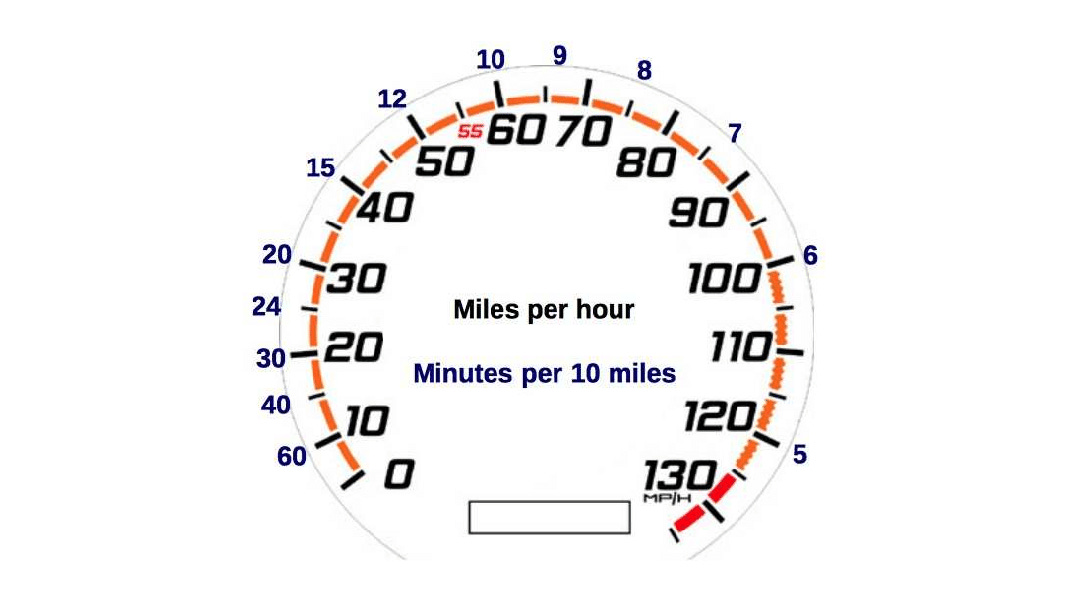

You may or may not be familiar with a speedometer—that circle of numbers that tells you how long it will take you to cover ten miles based on your speed. Perhaps you have noticed that the numbers of the outside are not as neatly spaced.

That’s because their value is irregular. In other words, beyond a certain speed, your gain drops. After 60/70 miles per hour, the gain from acceleration decreases.

“Some of you may have noticed this if you’ve got a GPS in your car. You’re driving on the motorway at 60, you realize you’re going to be five minutes late for an appointment, so you welly it. And after driving at an insanely fast and dangerous speed for about eight minutes, you suddenly realize your arrival time has only improved by one minute.

This is fascinating. Because to a physicist, they’re exactly the same. But when I present the information about time and distance in a different way, your reaction is now completely different. What it effectively says is: going quite a bit faster when you’re going slowly is a really big gain. Going very fast when you’re already going fast is the action of a dickhead.”

So that’s an interesting example to become aware that the risk/reward ratio has a threshold. There might be a good reason to have certain speed limits on the highway, after all. One example of how design tries to save us.

Train tickets is another example. If you’ve been to Europe and traveled by rail, you’ll be familiar with the machines at train stations. They’re awesome because they’re configured so you can search by destination. So you can choose whether to save time or money as you select your options.

Apparently not so in the UK (Rory’s example.) Are we too impatient to be intelligent? (He’s right in that open-ended questions are uncomfortable to business.)

And no, time is not a commodity, but because of the ‘time is money’ metaphor, it has become one. Thus we miss all kinds of opportunities to create value—in business and society—because that’s become ingrained in how we think (when we do at all.)

Here’s where culture comes in—and some clever time-saver goes ahead and turns an option, something we all love to have, into an obligation, that which we all must do and adopt.

“when one person does something, it’s an option. It’s something that somebody does. When these things become more widespread, they morph from being alternative options to being social norms, conventions from which you have no escape.”

Are we better off with technology adopted wholesale? If people and ideas are social prime movers, then we should know which parts to slow down.

“There are things in life where the value is precisely in the inefficiency, in the time spent, in the pain endured, in the effort you have to invest.”

Rory Sutherland

6/8 The magnitude of change we experience in the rhythms of earth is already wreaking havoc. Part of the problem is our inability to grasp it fully. How can we prepare for something we don’t understand?

Andri Snær Magnason’s on time and water explains.

“when you talk about the future, it becomes vague because, of course, the future doesn’t have anything. The future doesn’t have smell, texture, emotions. Like when you hear a word like ‘ocean acidification,’ it’s not connected to anything. It has no cultural significance. It’s just “ocean acid-i-fi-ca-tion.” What is that? It’s not connected to the Beatles. It’s not connected to any president. It’s not connected to any experience that we have. It’s not connected to Hitler. It’s not connected to the Second World War. It’s the biggest word in the world, because it’s about the biggest change that has happened chemically to the planet for the last fifty million years. It should be so loaded that we should cry when we hear it, because it should almost be a taboo to say it, if you don’t want to spoil the party.

It’s out there, but it doesn’t have any connections.”

Magnason uses mythology, storytelling, and history rather than just hard data and statistics.

The times we live in, he says, are most easily comparable to the ones you find in creation myths. He brings the issue down to human speed—we’re much better at stories than data—because things are not moving on geological speed anymore.

7/8 At home we get our different perspective in news by reading media in several languages. But many don’t have what Barbara Serra calls that ‘privilege.’ I knew since the age of six that I would speak English and it was a long road to get there.

Hence the majority of Americans, Australians, and Brits—we’re talking lots of people—read international news that are really anglophone news. The perspective or point of view of a culture and its language drives coverage.

“linguistic barriers (which are also national and cultural barriers) are real and have a huge impact on the careers of second-language English journalists. It’s part of a wider issue around diversity and representation that extends beyond journalism, but in this post I’ll focus specifically on the media and the impact the lack of diversity of voices has on which stories are highlighted and how they’re told.”

There’s no such thing as international news.

The accent thing in news broadcasting is an interesting issue. I write here, so you can’t hear mine. It’s there. Though I’ve done a lot of public speaking all over the world and recorded podcasts. Focus on clarity, and the accent fades into the background.

First-world voice, whatever that means, determines what we hear.

“That’s why this lack of diversity in international journalism dictates which stories are told, how they are told and who tells them. The world sees itself through the eyes of the anglophone media.”

8/8 Culture is the force that coordinates our actions. But, as Olivier Roy says, rather than it being a set of norms and codes we use to play together, it’s become a tool people use to position against each other.

Much of culture has become a game of signalling. I’ve also noticed it through my travels. Places that used to have a certain identity, special ways of doing (and thus ‘being’ when on the ground) have lost their sharp traits.

“Many houses in my neighborhood, for instance, fly variations of the American flag—rainbow flags, Blue Lives Matter flags, Thin Red Line flags, and so on. The flags are part of the culture wars. But, going by Roy’s account, they also reflect how much the ‘sociological grounding’ of common culture has eroded. Less and less in our culture is self-evident—the phrase ‘our culture’ might even seem suspect—and so the American flag, which should have some intrinsic, unchanging, obvious meaning (isn’t that the point of a flag?), has become a more fungible outward-facing sign, perhaps not too different from the campaign placards that we put in our yards. Flags are just vocabulary. Why not let them multiply?”

It’s not just the variations, it’s the size. As if, somehow, it could make up for courage sans community. The quantity of flags that show up for certain occasions an attempt to compensate for the lack of unity with the multiplicity. We lack a shared narrative.

Is culture dying? Is the tokenization of everything turning value into commodity?

Interesting questions for next year’s edition of festivalfilosofia, perhaps.

To get back to psyche.