The Most Important Speech

You can kill a person, but you cannot kill an idea. Especially when that idea means freedom.

On April 22 1924, a dapper Italian gets off the train in central London. He has no passport, the Italian government refused to grant him one. His mission is secret—to meet representatives of Britain’s ruling Labour party

He hopes to meet Ramsay MacDonald, the recently elected prime minister. Though the Labor party doesn’t hold a majority in the newly-elected British government, the man sees it as a beacon of hope.

The tireless defender of workers’ rights was being attacked at home—physically and verbally. Both fascist mobs and government-sympathizing newspapers shadow him looking for an opportunity, even in London.

At 38, Giacomo Matteotti1 made the trip as a last-ditch effort to stop Mussolini after his controversial election victory. Matteotti came from wealth. His family owned 385 acres in the Polesine region of north-eastern Italy. Yet in 1924 he was a refugee.

Declared enemy of the Italian state, the fascistis feared his exceptional eloquence. Matteotti expressed his opposition to Italy’s government both in parliament and in domestic and foreign newspapers.

Less than two months later, Matteotti was kidnapped and murdered while he walked to the parliament building in Rome. The crime shocked Italy and still leaves many questions unanswered more than a century later.

While the protagonists of his murder met with tragic and farcical destinies, Matteotti’s speech lives on as a beacon to freedom and decency. But I’m getting ahead of myself. There was a prequel to the most important speech.

The prequel

We have no idea whether Britain’s new prime minister and the co-founder and leader of the Italian Unitary Socialist Party met. What we do know is that Matteotti spoke to executive committees of the ruling Labour party and other workers’ organizations.

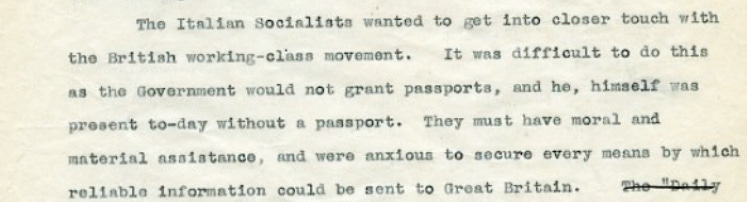

In the April 24 speech to those assembled he asked for “moral and material assistance” for Italian workers against fascist violence. His account of the troubles in Italy was so vivid that it got published in translation.2

“I remember what Matteotti told us during his visit to our country. He was talking about the suffering that was affecting the workers and socialist workers in Italy. The worst— he said— is what not even the strongest among us can bear: it is the fact that for two years now when you leave home in the morning you do not know if you will be able to return in the evening. He said this very calmly. And shortly after Matteotti returned to Italy, to die.”

Oskar Pollan, preface to The Fascists exposed; a year of Fascist Domination, 1924

Perhaps it was that speech and book to worry Mussolini.

Or perhaps it was the stop in London (Matteotti also went to Brussels and Paris.) Something else was going on. The American Sinclair Oil corporation had just signed an agreement with Mussolini.

In London Matteotti found time to deal with one of the issues closest to his heart—the defense of Parliament and its irreplaceable legislative and control function and the scandal of the so-called ‘dirty decrees’ on gambling dens and oil exploration.3

It seems that, in exchange for a bribe, Italy’s prime minister granted the company a monopoly on oil exploration and extraction in parts of Italy. Some suggested the Labour government might have provided Matteotti with proof.4

2 million USD (about 40 million in today’s dollars) was all it took.

After praising the courage and the intellectual and moral integrity of Giacomo Matteotti, party leader H. N. Brailsford5 established a correlation between the assassination and Matteotti’s denunciations:

Against the regulation of gambling houses, which allowed the Ministry of the Interior to open gambling dens under its direct control.

And the other campaign conducted by Matteotti against the decree (due to its obscure nature and damaging to national interests) which entrusted the Sinclair Exploration Company with the monopoly of oil research in Sicily and Emilia-Romagna.

The thoughts and ideas Matteotti and the English Labour Party exchanged on the relationship between executive and legislative power were particularly relevant.

“The fascist government intends that the Chamber only serves to approve what it does, indeed it believes that Parliament can only exist on condition that it never goes against the Government. And just as the fascists have declared that the Government is above the electoral response, so it believes itself to be above any vote of the Chamber.”

Giacomo Matteotti

Matteotti felt that bureaucracy, vested interests, and plutocratic groups had replaced the pre-eminent legislative function of Parliament. Oil and gambling dens demonstrated the regime’s business bent.

His appeal didn’t fall on deaf ears.

“Comrade Matteotti, secretary of the United Socialist Party, was well known in England. His recent visit here to London, in defiance of the Fascist authorities who tried to prevent it, certainly did not please Mussolini. In the meetings and discussions that Matteotti had had in London, in particular with A. A. Purcell, president of the General Council of the British Trade Unions Congress and with C.T Cramp, president of the Labour Executive, we had been struck by the good sense and moderation of his analysis, the rigor and knowledge of financial problems, the moral integrity of his personality, his courage and his great sense of justice.”

Daily Herald, June 16, 1924

But it didn’t spare the deputy member of Italian’s Parliament.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On Value in Culture with Valeria Maltoni to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.