On the Value of Unread Books

"Books are not made to be believed, but to be subjected to inquiry. When we consider a book, we mustn't ask ourselves what it says but what it means." Umberto Eco

The more we learn, the more we realize how much more we have not explored and understood. In the same way we have untapped potential, the books we haven't yet read represent our potential learning.

It’s a concept author Nicholas Nassim Taleb1 called an ‘antilibrary,’ with reference to Umberto Eco’s private library.

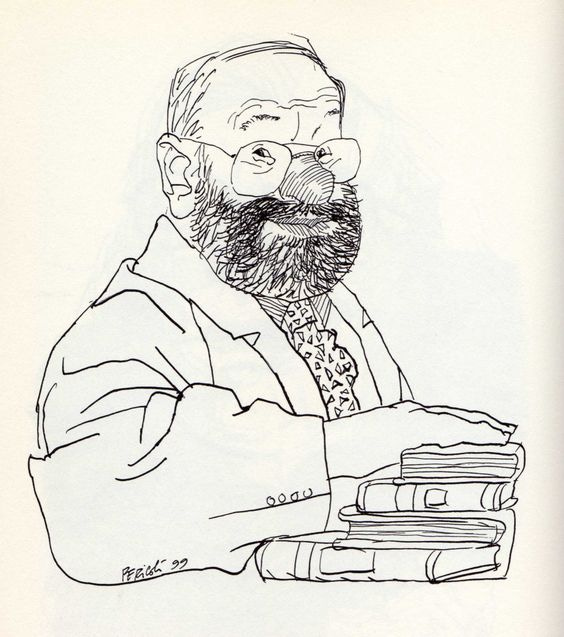

Eco was an Italian author and professor of semiotics2 whose first novel, The Name of the Rose, catapulted him to international fame, selling more than 50 million copies and counting.

A prolific writer, his works spanned stories for children, pieces of literary criticism, academic texts on semiotics, studies of everything from medieval aesthetics to modern media, and everything in between

From The History of Beauty where he explores the nature, the meaning, and the very history of the idea of beauty in Western culture to the witty and irreverent How to Travel with a Salmon, a collection of essays.

Writers are also prolific readers, and Eco was no exception. He was well-read in a number of disciplines, from literary to intellectual history, cultures, languages, and places—we find many of those references in his characters and stories.

“The problem with the Internet is that it gives you everything—reliable material and crazy material. So the problem becomes, how do you discriminate?” Eco’s idea was that we should be in relationship with books, and subject what we read to inquiry.

“Books are not meant to be believed, but to be subjected to inquiry. When we consider a book, we mustn’t ask ourselves what it says but what it means.”

With greater access comes greater responsibility. We need to separate bedrock from sand—to think critically about what we read is a good starting point. Many individuals and organizations may have forgotten how to create shared understanding.

Books provide context around a topic, which no number of links will ever give you. Context is what gives you value. And I would be remiss if I didn’t provide some to help make sense of why Eco believed in unread books.

The truth of signs

Now think back to 1327, the year Adso of Melk finds himself in a remote monastery with Brother William of Baskerville. The powers that be suspected heresy has taken root among the monks.3

It was a time of profound transformation—the rulers of the time feared what imagination, curiosity, and new ideas would bring about.

The more things change, the more they stay the same, eh? When it comes to human nature there are two main movers—love and fear, mostly fear. Imagine you overheard the conversation Adso and Brother Williams had on the seventh Day and night.

BW—“I have never doubted the truth of signs, Adso; they are the only things man has with which to orient himself in the world. What I did not understand is the relation among signs . . . I behaved stubbornly, pursuing a semblance of order, when I should have known well that there is no order in the universe.”

A—“But in imagining an erroneous order you still found something. . . ”

BW—“What you say is very fine, Adso, and I thank you. The order that our mind imagines is like a net, or like a ladder, built to attain something. But afterward you must throw the ladder away, because you discover that, even if it was useful, it was meaningless . . . The only truths that are useful are instruments to be thrown away.”

While you listen, think of our propensity in business to fall in love with our ladders. Brother Williams tells Adso that many hypotheses, false though they may be, can still lead one to a correct solution.

“The only truth lies in learning to free ourselves from the insane passion for the truth.”

Though we might not like to admit it, we do know all too well that power doesn’t come from truth. There are all kinds of others means to get it. In fact, the closer we get to something that feels truthful, the faster we seem to run.

“Because learning does not consist only of knowing what we must or we can do, but also of knowing what we could do and perhaps should not do.”

Yet, so much is done ‘because we can,’ and so little ‘because we must.’ And so while certainty remains an impossibility, we can rely on our imagination, curiosity, and the ability to create new things.

“Love is wiser than wisdom.”

Alas, instead we fall in love with the organizing symbols. We’ve all read case study after case study of companies and people who have excelled— they figured out innovation, growth, leadership... measured in the hard currency of material wealth.

Many have written on and extrapolated the lessons we can learn from these people and companies. They’re fascinating stories of achievement and often examples of intelligence, courage, determination, magnanimity, and other human qualities.

It’s tempting to want to imitate and emulate our heroes of the day. We’re like children who have had an exhilarating experience (in our minds) and want to recreate it. The problem with that thinking is that we’re not exactly in the same conditions.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On Value in Culture with Valeria Maltoni to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.