Published n. 1: links and commentary

A new series on value to culture—writing for humans, by humans.

Welcome Fall/Indian Summer, and welcome new subscribers, especially those of you who chose the paid option. Thank you, grazie mille, Danke sehr, merci. Many thanks to those of you who’ve forwarded and shared On Value in Culture with your network.

I value your support for the work I do.

Meaning and depth are a long game and some days are easier than others. How we think, talk, and write about our lives has collective implications—for mental health as for the health of our organizations. Narrative identity is powerful.

Good writing for humans, by humans is the theme of the inaugural thread. Next week, I’m inaugurating a mini-series. See what you think of both, the links/comment thread, and the mini-series.

Published has root in (Lat.) publicare ‘make public,’ from publicus ‘public, pertaining to the people.’ Which then turned into ‘open to general observation,’ from Old French public (c. 1300.) The meaning ‘open to all in the community, to be shared or participated in by people at large’ is from 1540s in English.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

–Joan Didion

On Value in Culture is a reader-supported guide to framing in narrative, language, books, value & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by paid subscription.

1/12 the most read and shared articles from On Value in Culture:

How ‘Revenge’ Ruined Travel—We closed down just as the world started reopening up.

(🔒) How an engineering company defined ‘value’—And how the answer changed since Aristotle's 4th C BC definition.

Why we need cinema—Stories continue to ignite our imagination.

(🔒) Things begin to exist when we notice them—Michela Murgia—stating the obvious is important to democracy.

A more fulfilled life—Look beyond the myth, and you will find a fascinating hidden world of possibilities.

(🔒) Solitude gains value when we use it to reconsider—Rainer Maria Rilke is the most modern of poets from the last century.

A story about screens—How we've come to embrace factoids in place of knowledge.

2/12 On The Intrinsic Perspective, Erik Hoel says Culture is Downstream of Money:

“If I said, ‘Nerds are in’ what would your first reaction be? I think the almost knee-jerk response would be to disagree. Although this is strange, because the very word ‘nerd,’ once almost an accusation, seems to have lost all its bite compared to twenty years ago. So why does the phrase ‘nerds are in’ ring untrue?

Nerds can’t be ‘in’ because the entire culture is now one of nerds. There is no ‘out.’ Nerds so dominate the landscape they don’t even exist as a category anymore. They have triumphed so completely over their archetypal rival, the jock, that even the most athletic high school boy is now a Janus with two faces.

All to say, there are no nerds anymore, which is how you know they won.”

What’s your first reaction as you read this? The implication is that because the people high on the hierarchy are ‘nerds,’ right now it’s become a desirable thing—to be called a nerd.

The implication Erik makes is that whoever is getting insanely rich now will drive culture in the foreseeable future. In this scenario, the only political wind (and will) sides with wealth. A return to the past kings (and occasional queen)?

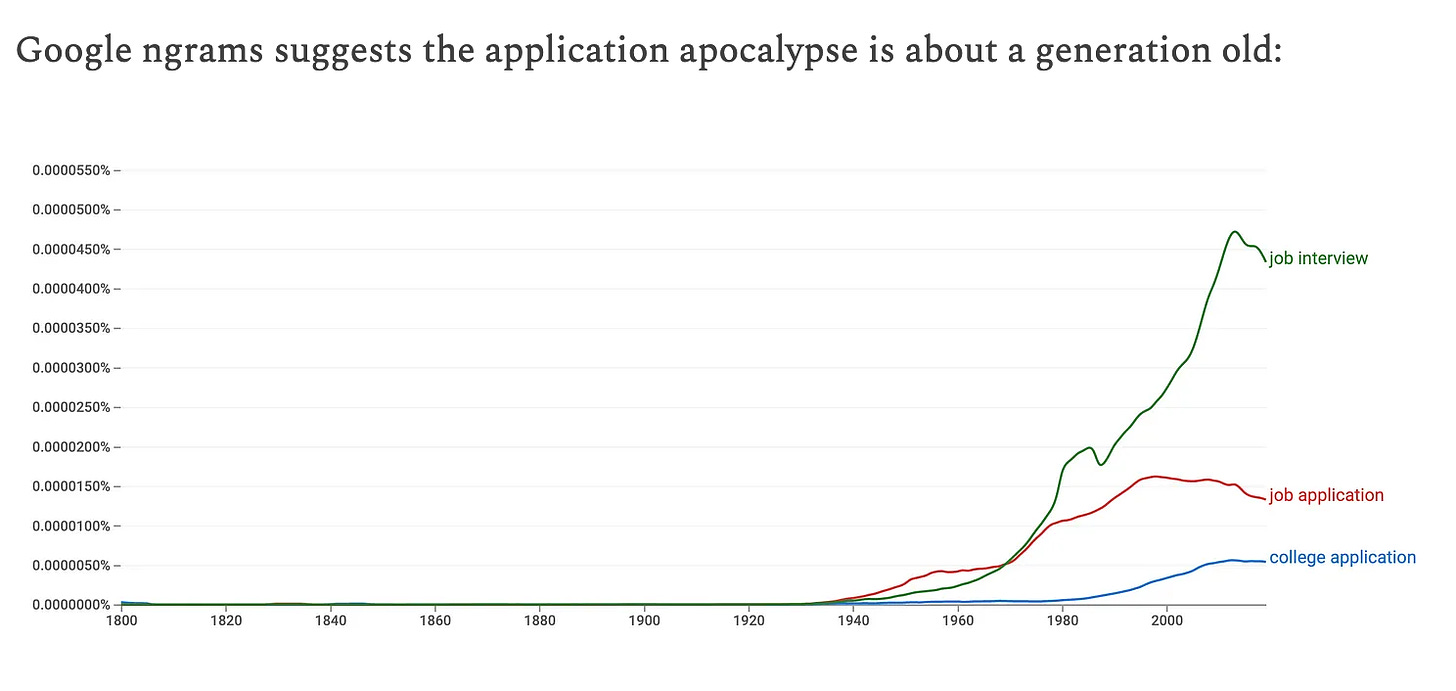

3/12 We need to imagine new ways of picking people. At Experimental History, Adam Mastroianni wrote about application culture:

“We apply for everything: scholarships, internships, jobs, promotions, apartments, loans, grants, clubs, conferences, prizes, and even dating apps. A kid today might apply for every school they ever attend, from preschool to graduate school. Even if they get in, they’ll find they’ve merely entered the lobby, and every room beyond requires another application. Want to join the student radio station, take a seminar, or work in a professor’s lab? You’ll have to apply. In undergrad, being unpaid tour guide required an application—and 50% of people were rejected!”

How much of your life do you spend applying for things? How much of your life do you spend sifting through the things other people apply for? Time, energy, and physical costs that could go to generate value doing something else.

Also, take a look at how the language we use changes (and changes us)—" relationships turn into connections, our passions become activities. Who wants their lives to be just a track record?

“If you reward people for lives that look good on paper, you’ll get lots of good-looking paper and lots of miserable lives.”

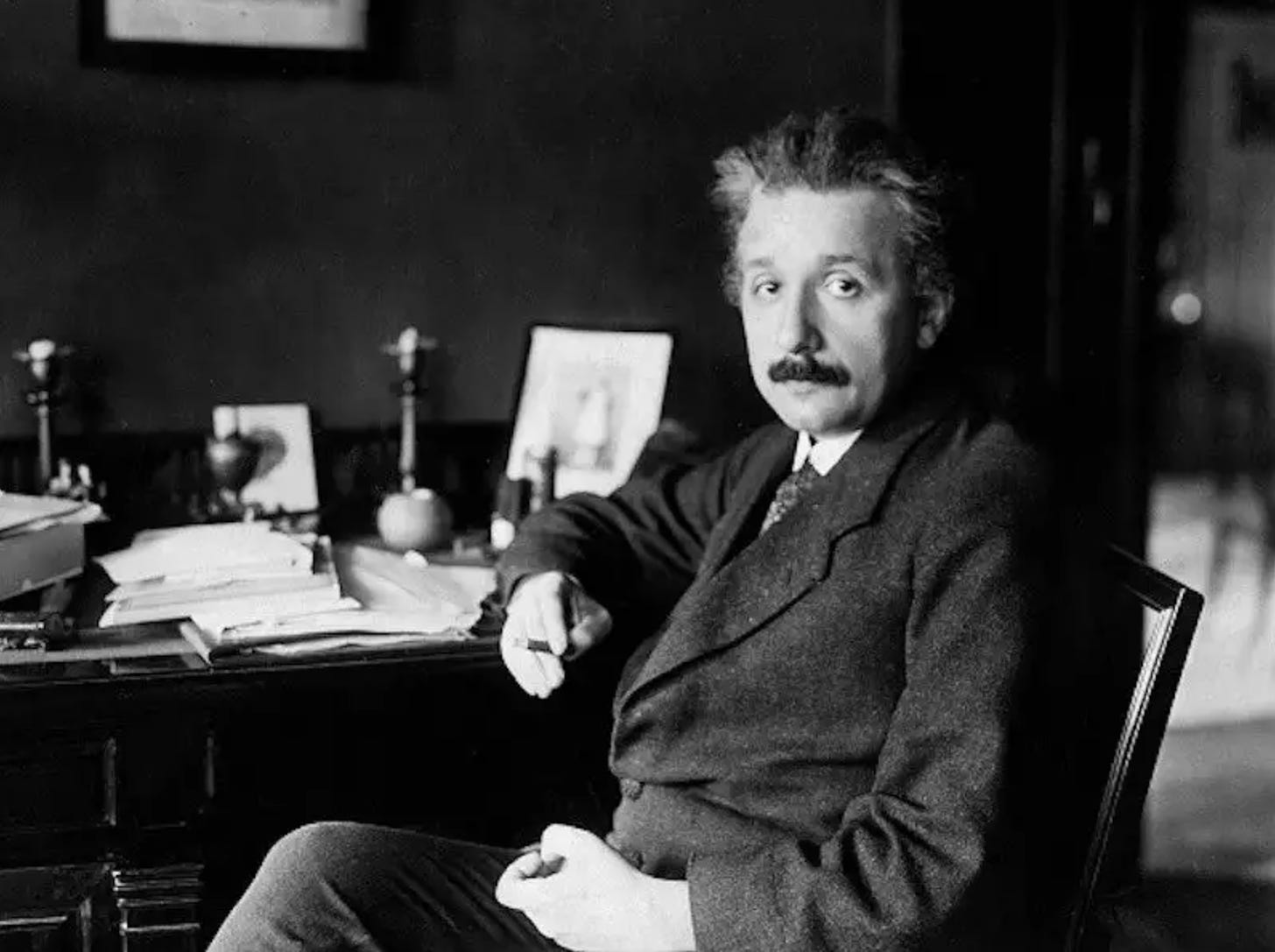

4/12 In Rest at Strange Loop Canon, Rohit Krishnan makes the case for sabbaticals:

“Today, it’s nearly impossible for most professionals to enjoy such intellectual freedom. In the always-on economy, taking months or a year for unstructured exploration has become extinct. Two weeks of hurried vacation is the norm, if you’re lucky. Sabbaticals are a quaint relic, reserved for tenured academics. Yet history reveals the immense value of this ‘long time.’”

And we’re paying the price. Creativity has stagnated across industries. The few who escape enjoy epiphanies like Einstein in 1905. The always-on economy has robbed most professionals of this gift.”

Do look at the history of genius, and you’ll find that in addition to private tutors, many did travel, often to Italy, to recharge, change perspective and see things in a new light.

We undervalue thought in favor of action. But if you don’t invest in mind wandering, you’re endlessly body-wandering.

5/12 And talking about body-wandering, The New Yorker on people of the Fall:

As opposed to people of August, via Liza Donnelly of Seeing Things, writer, journalist, cartoonist for The New Yorker.

6/12 Sam Atis at All That is Solid says Most Advice is Pretty Bad. You’ll find many of the usual tropes in the article. “I think sometimes the problem is that bad advice gets a lot of hits and attention because it can be enjoyable to read, and it can also be motivational.”

To be good, advice needs three main components—being not obvious, actionable, and based on true insight. On behalf of many of the specialists among you, it’s worth pointing out that (Ben Kuhn’s article example):

“The last thing this helped me realize is that specialists have a lot of non-specialized problems. In one sense, this is so well known it’s become a cliché—the engineer who just wants to crank out code all day, the philosophy professor with their head in the clouds. But the cliché doesn’t really describe me or most engineers or philosophers I know, who are broad-minded enough to be happy thinking about things outside our assigned specialty. Even for us, though, we can often increase our impact a lot by improving our generalized effectiveness.”

Talking to people regularly about your work and what you’re doing can be very helpful—even when they don’t knows a lot about the kind of work you do.

7/12 Angela Nagle frames the cultural valence of Unremarkable Clothes:

“Interestingly today, bold fashion statements do live on but in designated zones and on the internet. The time and energy poured into the production of online self portraits in striking outfits is in total contrast to the expression on the street level. Is it that we don’t feel the people in real life are real enough to be worth dressing up for?

It is a gender neutral and also a classless non-style, which has developed with greater economic inequality but more abundant cheap goods, along with the disappearance of the aspirational working class and elite styles of the mid-century. It is also an ageless style and not in the way that a little black dress is.”

Has subculture disappeared along with counterculture? I’m in favor of style as a form of self-expression, with a nod to aesthetics, beauty, and taste. Is the question we’re tacitly asking ourselves the one Angela proposes—who would we be dressing up for?

We’re at camouflage. Mass-produced for mass-worn. Is it acquiescence to perceived lack of agency? Perhaps, if “we don’t truly know who we are and what we want to be known as, it is best to become one with the crowd,” as Shifra says in the comments.

I’ve noticed the baggy jackets, formless shirts, wide-legged pants, leisurewear and well-worn apparel are in. What’s on offer is itself unremarkable. Except for specific, designated areas where people go to ‘see and be seen,’ like street fashion (with long tail on Instagram.) High fashion still offers colors, materials, textures, and lines.

Perhaps it’s the desire to belong in the absence of a cohesive sense of community, to have a feeling of connection.

On a side note, in the rare instances in which I buy apparel, I buy in Italy (and Europe.) Being in Italy is a permission to upgrade style—at any age. While in Lucca I crossed paths with a British woman. She was flawless casual chic and in her '60s. Effortlessly feminine, without making any statements. My clue that she lived there was a comment she volunteered about her neighborhood.

8/12 George Lakoff on Why is empathy central to democracy? on FrameLab:

“Empathy is the central component of a healthy and functioning democracy. That’s because democracy is based on the principle of equal representation. Empathy is necessary to understand and respect the perspectives and experiences of diverse individuals and communities.

In a democracy, empathy can help foster social cohesion and build bridges between groups with different interests and beliefs. It can also encourage citizens to engage in civic activities and to work together towards common goals.”

It’s not sufficient, we also need “a robust legal system, freedom of speech and assembly, and an engaged and informed citizenry.” But how we define and frame concepts determines what happens to the other requirements.

9/12 Carissa Potter is Bad at Keeping Secrets. She asks How do you know when to give up?

Can we change our patterns?

10/12 Elizabeth Held writes three book picks based on the news, pop culture, reader requests, and her own whims in What to Read If… You Recently Watched Eight Seasons of ‘Suits’ and (not related) attended a state fair or celebrated India’s moon landing.

I love this concept of pairing what’s going on in culture with readings. There’s a certain magic in reading the right book at the right time. Elizabeth goes beyond the bestseller lists and the books already earning buzz.

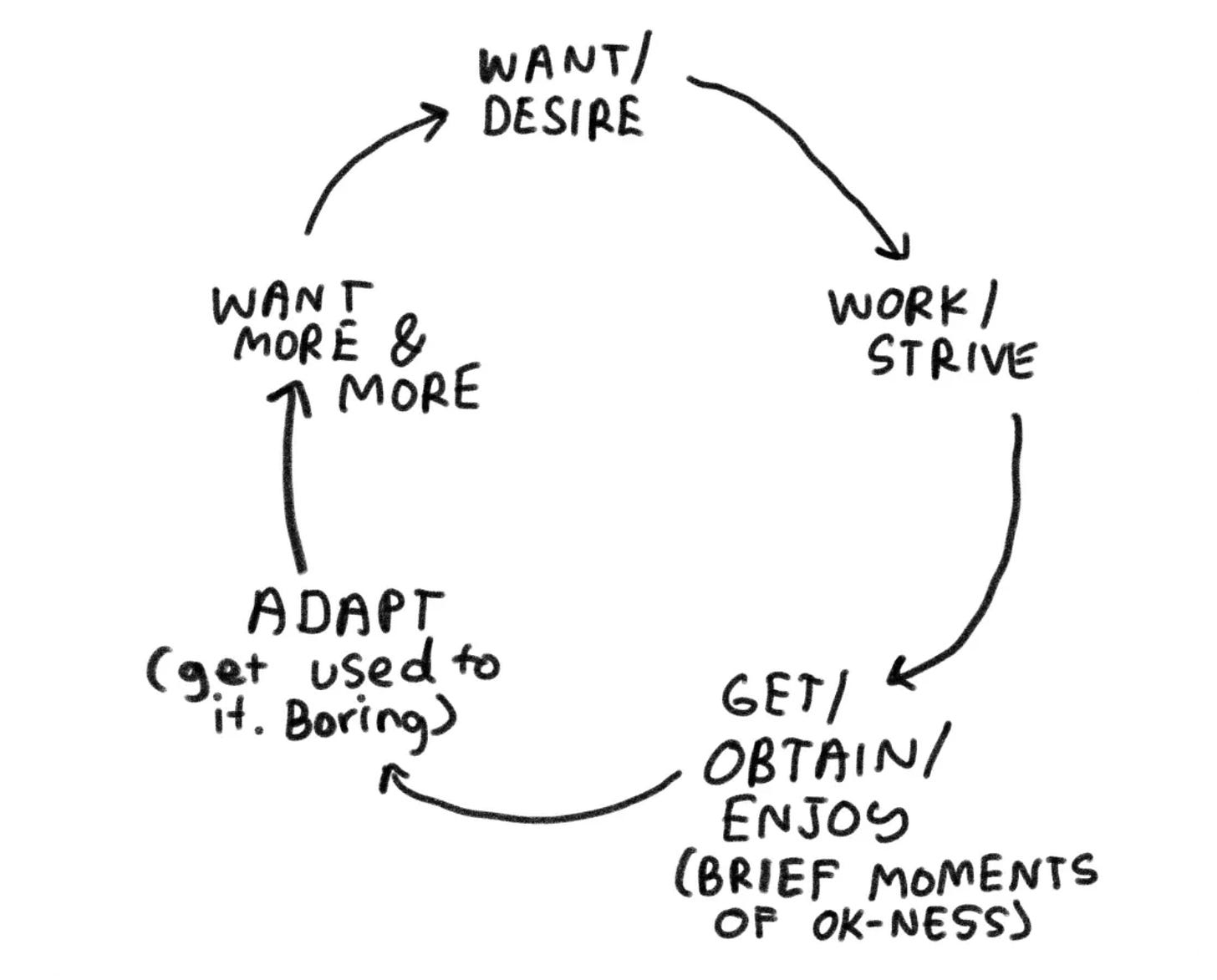

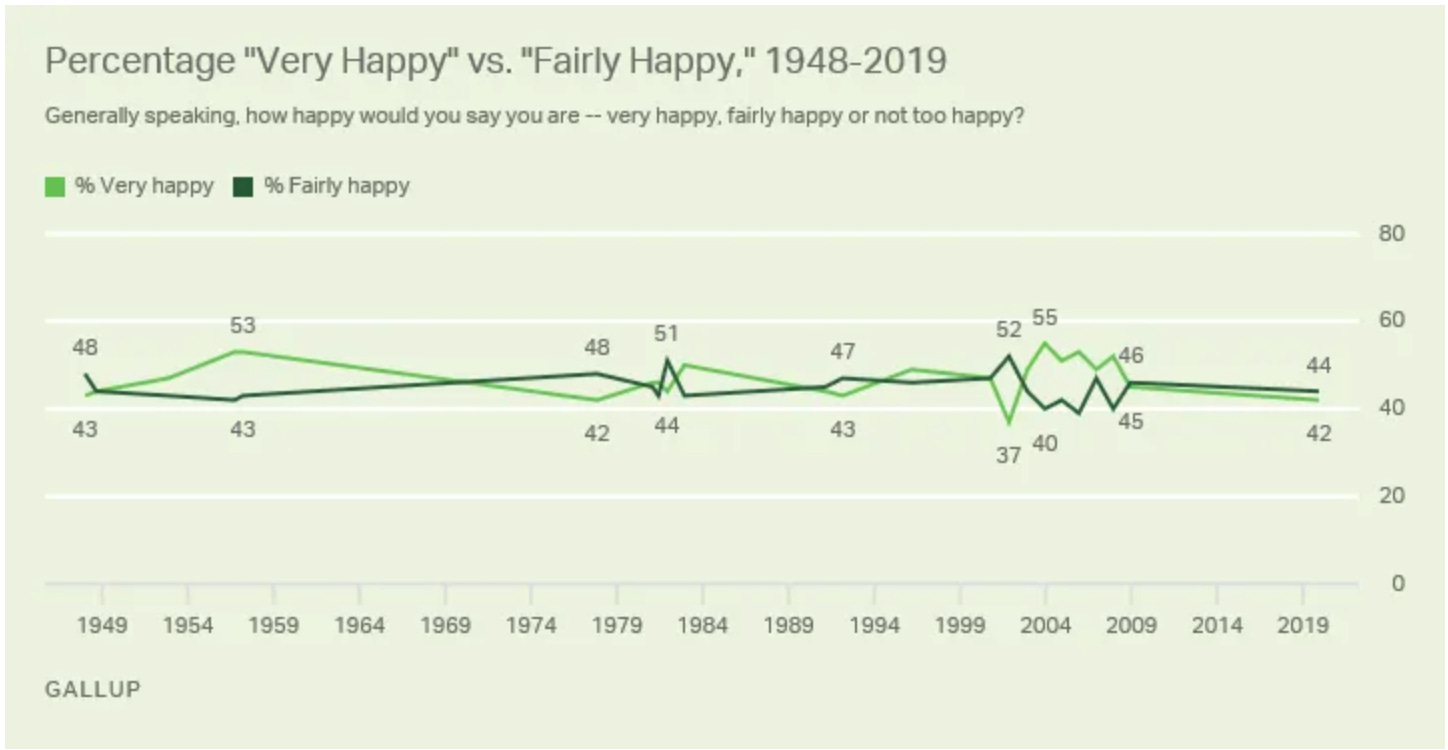

11/12 I’m sharing another article by Adam Mastroianni because it attempts to answer a question I’d wager you and I have asked ourselves often—Why aren’t smart people happier?

“Spearman was right that people differ in their ability to solve well-defined problems. But he was wrong that well-defined problems are the only kind of problems. ‘Why can’t I find someone to spend my life with?’ ‘Should I be a dentist or a dancer?’ and ‘How do I get my child to stop crying?’ are all important but poorly defined problems. ‘How can we all get along?’ is not a multiple-choice question. Neither is ‘What do I do when my parents get old?’ And getting better at rotating shapes or remembering state capitols is not going to help you solve them.”

Other poorly defined problems that get people in trouble— ‘maintain a basic grip on reality,’ ‘be a good person,’ and ‘don’t make any life-altering blunders.’ These are the kinds of questions we need to ask—and answer as best we can—more and more.

All the progress we’ve made on solving well-defined problems, and we’re not happy. Being alive is a poorly defined problem. We haven’t yet defined the problem of ‘living a happy life.’

Adam makes the argument in a few ways—looking at it from different angles. Which is how I’d like to think about any questions. Is the problem one of definition? Define intelligence by dividing it based on solving well-defined and poorly defined problems and you open up a new line in inquiry.

The ancient thinkers did ponder more about what makes a good life. They distinguished between sophia and phronesis. Sophia is timeless true knowledge, like the speed of light in a vacuum. Phronesis is contingent, high-context knowledge like how to solve a social problem or motivate warriors.

In the Ethics, Aristotle says that phronesis is “what is suitable is . . . relative to the person, the circumstances, and the object” (1122a25-6), while sophia “will study none of the things that make a man happy” (1143b119). Humans are good at ‘close-reading.’

Without going all the way back to ancient times, my grandmother (and great-grandmother) were a wonderful reference for answering ‘what makes a good life.’ I also like to expand the question of happiness to a broader perspective.

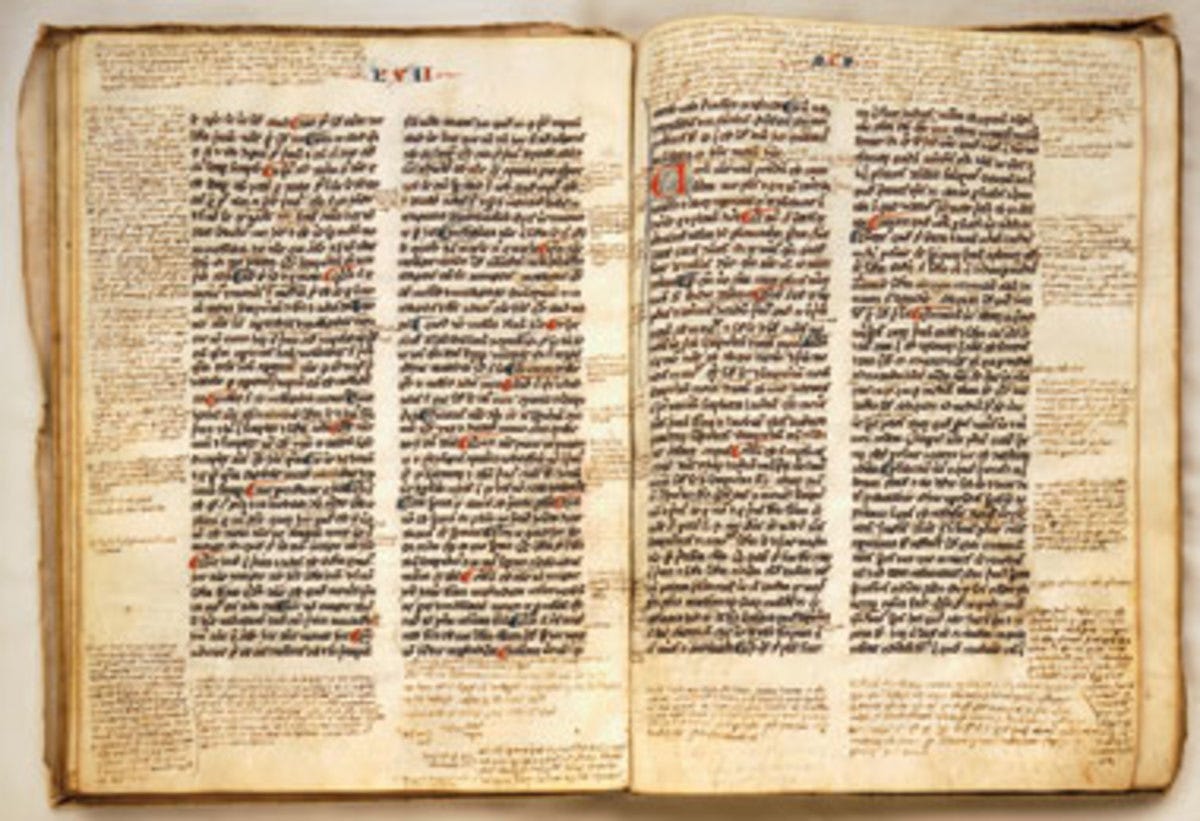

12/12 Writing in Atlas of Wonders and Monsters Étienne Fortier-Dubois examines what distinguishes the two main branches of knowledge, a topic I explore often. The Difference Between Science and the Humanities is Reading the Classics:

“But while the STEM students do more math, there’s one thing that the humanities students spend far more time on than the science types: they read old texts.

If you’re interested in philosophy, you have to read Plato and Aristotle — and Kant, and Nietzsche, and Sartre, and so on and so forth. If you’re interested in English literature, you have to read Shakespeare and many others.

If you’re interested in religion, you have to read the old sacred texts as well as theologians from centuries ago. It’s fine to read about all these famous philosophers and poets and thinkers, but it’s no substitute for the real thing.”

Note that science means knowledge (Lat.)

Today, you need to decide which path to take. Universities have very different faculties for each. The norms of what makes for good intellectual work differ between the two. Academics who identify with one may mock the other.