“Fahrenheit 451” came out in 1966. François Truffaut directed the British dystopian science fiction film—his only not in French language and first in color. Based on the 1953 novel of the same name by Ray Bradbury, it showcased Truffaut’s love of books.

The film, which depicts a controlled society in an oppressive future, was a commercial failure. In this alt-future, the job of firefighters is to track down books and burn them. I remember feeling repulsed by the premise when I watched it.

Anyone who’s read the book or watched the film may remember that books were banned and burned to prevent thinking and revolution. However there’s deeper significance in both the book and the film—screens turn us into morons.

Reminder: You can get extra insights—in-depth information, ideas, and interviews on the value of culture.

Join the premium list to access new series, topic break-downs, and The Vault.

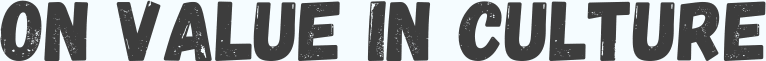

Oskar Werner, an actor difficult to work-with, ended up playing Guy Montag, one of the firemen in the leading role. Truffaut had a terrible time making the film, which he had first planned for 1962 in New York with Paul Newman as the protagonist.

The director documented the travails in his journal of the shoot published in two parts in Cahiers du Cinéma.1 Truffaut’s plans included making the film in French, with Jean-Paul Belmondo or Charles Aznavour as the protagonist.

To make the film in English, he thought of Peter O’Toole, then Terence Stamp. To cope with his loneliness as he worked in a country where he didn’t speak the language he started writing a journal. Besides Warner, he had problems dealing with the studio. (It was a larger-scale production. Until then, he had worked only with small crews and budgets.)

In the plot, firefighter Montag meets one of his neighbors, Clarisse. She’s a young schoolteacher who may be fired due to her unorthodox views. The two have a discussion about his job. She asks whether he ever reads the books he burns.

Curious, Montag starts hiding away some of the books, so he can read them. Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield is his first. His reading changes him, which leads to conflict with his wife Linda (in the film.)

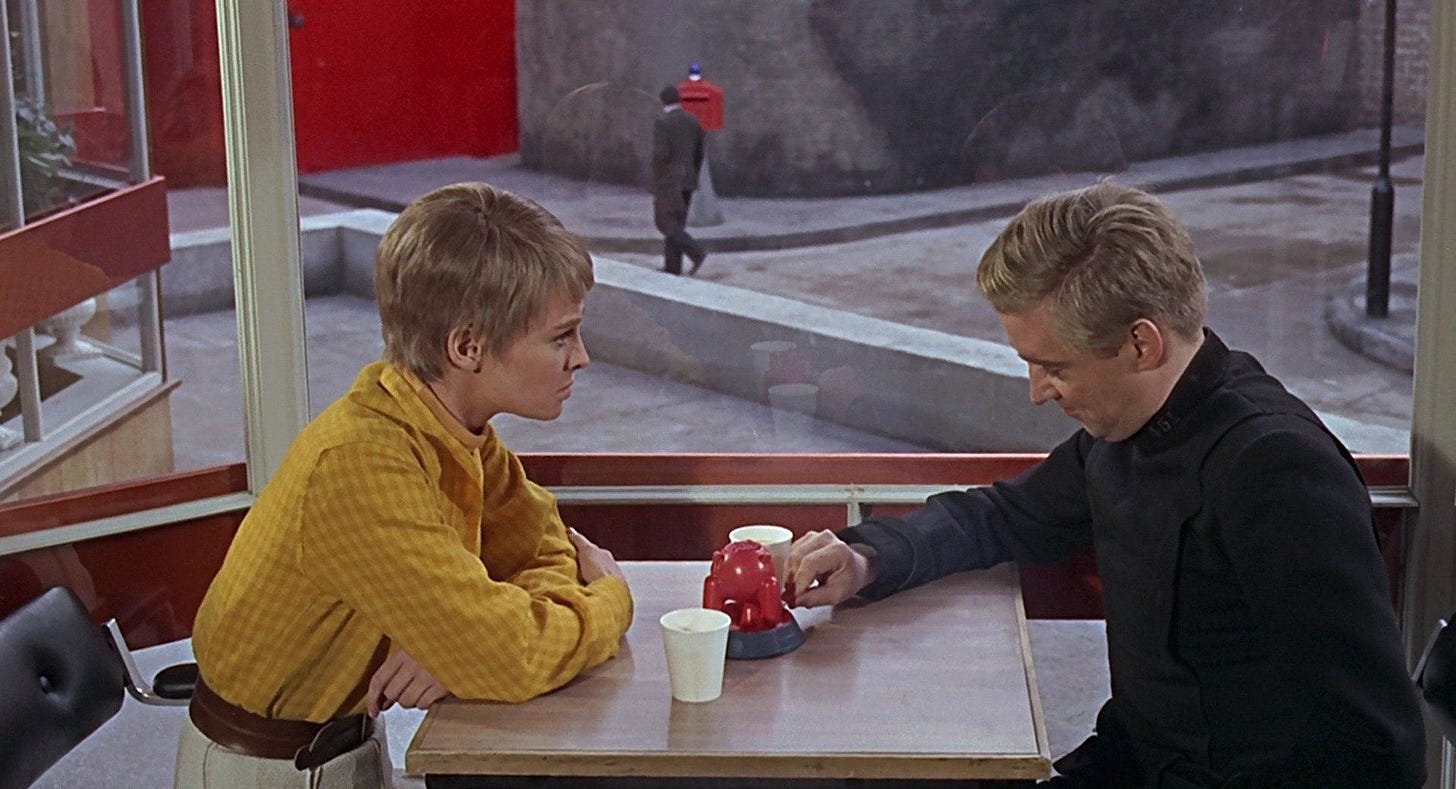

Linda is more concerned with being popular enough to be a member of “The Family,” an interactive television program that refers to its viewers as ‘cousins.’ In the book, Bradbury describes the screen as ‘parlor walls.’

The film came out a year after “Alphaville” by Jean Luc Godard. In a letter he sent his friend, Truffaut said, “You mustn’t think that ‘Alphaville’ will do any harm whatsoever to ‘Fahrenheit.’” But it did, because Godard’s was far more radical and critical.

While Godard used language, attitude, and Eddie Constantine to create a future that looks very 1960, Truffaut had the upper hand in artistic quality. Richard Brody in The New Yorker says:

from an artistic point of view, “Fahrenheit 451” is one of Truffaut’s wildest films, a coldly flamboyant outpouring of visual invention in the service of literary passion and artistic memory as well as a repudiation of a world of uniform convenience and comfortable conformity, in favor of the ramshackle cell of culturally devout outsiders, resistance fighters in the name of art.

The wildness of the film represented a sort of ideal, one that he recaptured only intermittently, albeit gloriously, in the films that followed (most fully, in such films as “A Gorgeous Girl Like Me,” “The Man Who Loved Women,” and “The Woman Next Door”); “Fahrenheit 451” marks a break with the low-budget, street-level cinema; it’s tinged with regret, with a retrospective wistfulness that would mark the rest of his films.

In a world where technology was warping interpersonal contact, “Alphaville” was also about the importance of love and human connection. After a particularly harrowing book burning that ended up burning the collector with her books, Montag tries to tell Linda and her friends about the woman who martyred herself in the name of books.

At the house of an illegal book collector earlier in the day, fire captain Beatty tells Montag how books make people unhappy and make them want to think that they are better than others, which is considered anti-social.

The book collector was an old woman Montag saw with Clarisse a few times during his rides to and from work. She refused to leave her house, opting to burn herself and the house to die with her books.

At home, Montag confronts his wife and her friends about knowing anything about what’s going on in the world. He calls them zombies and tells them that they’re just killing time instead of living life. He then forces them to sit and hear him read a novel passage. One of Linda’s friends breaks down and cries over repressed feelings.

Ray Bradbury himself said that Fahrenheit 451 is not, mainly, a searing indictment of government censorship. In 2007, Bradbury said neither it was a response to Senator Joseph McCarthy, whose investigations had (in 1953) already instilled fear and stifled the creativity of thousands.2

“Television gives you the dates of Napoleon, but not who he was.” Bradbury says, summarizing TV’s content with a single word that he spits out as an epithet: “factoids.”

“Useless,” Bradbury says. “They stuff you with so much useless information, you feel full.”

In the book, Bradbury refers to televisions as ‘walls’ and its actors as ‘family.’ The author imagined a democratic society whose diverse population turns against books— whites reject Uncle Tom’s Cabin and blacks disapprove of Little Black Sambo.

He imagined not just political correctness, but a society so diverse that all groups were ‘minorities.’ People at first condensed the books, they stripped out more and more offending passages. Then all that remained were footnotes hardly anyone read.

It was only after people stopped reading that the state employed firemen to burn books. The flat screens used in the book as television broadcasted meaningless drivel to divert attention, and thought, away from an impending war.

Bradbury was worried about people being turned into morons by TV. In the film, there are ‘book people,’ a hidden sect of people who flout the law, each of whom has memorized a book to keep it alive.

Truffaut’s adaptation is differed from the novel. He portrays Montag and Clarisse falling in love. Julie Christie plays two characters—Clarisse and Montag’s wife Mildred (Linda in the adaptation.) Bradbury said it was a casting mistake.3

The author was pleased with the film, despite its flaws. He was particularly fond of the film’s climax, where the Book People walk through a snowy countryside, reciting the poetry and prose they’ve memorized, set to Bernard Herrmann’s melodious score.

It’s the temperature at which books burn. “The only difference between historians and novelists is that the novelists can invent,” said Alessandro Barbero (who talked about the history of book-burning.)

Bradbury, has written more than fifty books. He studied Eudora Welty for her “remarkable ability to give you atmosphere, character, and motion in a single line.” Growing up, his favorite writers included Katherine Anne Porter, Edith Wharton and Jessamyn West.4

“My stories run up and bite me in the leg—I respond by writing them down—everything that goes on during the bite. When I finish, the idea lets go and runs off.”

The author didn’t consider science critical to his writing, but ‘incidental’ to it. He claimed to not be over-interested in the development of science, but hoped to use it as a form of social commentary and an allegorical technique.

“In writing the short novel Fahrenheit 451 I thought I was describing a world that might evolve in four or five decades. But only a few weeks ago, in Beverly Hills one night, a husband and wife passed me, walking their dog. I stood staring after them, absolutely stunned. The woman held in one hand a small cigarette-package-sized radio, its antenna quivering. From this sprang tiny copper wires which ended in a dainty cone plugged into her right ear. There she was, oblivious to man and dog, listening to far winds and whispers and soap opera cries, sleep walking, helped up and down curbs by a husband who might just as well not have been there. This was not fiction.”5

You could easily replace the small radio with a large smartphone, and you’d have the same scene. Even worse when instead of walking, it’s driving. Bradbury’s book also contained a critique of political correctedness.

“How does the story of Fahrenheit 451 stand up in 1994?

R.B.: It works even better because we have political correctness now. Political correctness is the real enemy these days. The black groups want to control our thinking and you can’t say certain things. The homosexual groups don’t want you to criticize them. It’s thought control and freedom of speech control.”6

In a 1982 essay, he wrote, “People ask me to predict the Future, when all I want to do is prevent it.” Montag’s wife Mildred (the name was changed to Linda in the film) takes sleeping pills to separate herself from her parlor walls at night.

Mildred’s overdose opens the book. She doesn’t even realize how serious that is. Because medicine is within reach to help people deal with the side effects of screen attachment—it eliminates memories and increases the checked out state of everyone.

Screens in the book are the product of poor political choices. Today, they’re the things that drive the proliferation of disturbing narratives. Censorship is part of both scenarios.7

Fahrenheit 451 illuminates the flaws at structural level. Its a world designed to prevent people from thinking, connecting, questioning, and being physically engaged. Clarisse is the only character who appears to have preserved the characteristics of the child.

Clarisse explains to Montag how to see the world differently. She invites him to open his eyes, to ask questions, to engage with the physical world, and to challenge the social order. She’s the only character who criticizes the status quo.

While Montag’s boss is fully aware of how society needs to function. To ban books reinforces political control. As a firefighter, his job is to repress and restrict. Captain Beatty enables the structural conditions that support repression.

If you want to be revolutionary, it looks like preserving knowledge and developing critical thinking are part of it. There was a time when people saw education as a way forward. The ‘book people’ embody that reverence for embracing, saving, and sharing knowledge from books.

“I get letters from teachers all the time saying my books have been banned temporarily,” says Bradbury in the clip. “I say, don’t worry about it, put ’em back on the shelves. You keep putting them back and they keep taking them off, and you finally win.”

“You do the job. You’re the librarian. You’re the teacher. Stand firm and you’ll win. And they always do.”

It started small, with people giving up certain parts. Soon enough they were reduced to footnotes they didn’t even read. Then the books got banned, and burned. And finally, they got burned with their books.

That’s how we got to a world filled with limits and barriers. Our culture judges people incessantly. People joined in the judging and limiting—don’t do this if you want to publish, don’t do these things if you want a job, etc. You cannot make a living writing (well, that one is true for most of us.)

But, you and I are part of that culture. We can change things. In the same ways Clarisse and the ‘book people’ remained curious, and taking initiative to explore a different way like Montag.

I can tell you from experience that when you don’t ‘fit in’ you face challenges.

As a writer who wants to get published, I face rejection daily. But I don’t throw my books in the trash (Stephen King did that with his first novel), I simply bide my time. The market uses a narrow and incomplete method for measuring value.

In the current system, value is mostly subjective, it depends on commercial (and approved) attention:

Orwell called this the ‘prevention of literature.’8 “In our age, the idea of intellectual liberty is under attack from two directions. On the one side are its theoretical enemies, the apologists of totalitarianism, and on the other its immediate, practical enemies, monopoly and bureaucracy.”

What has become known as ‘cancel culture.’9 “Six Dr Seuss books will no longer be published because of racially insensitive imagery, the company that preserves the author's legacy has said.”

Aging badly for books means ‘pulping.’10 “The context of this book is that it’s aimed at boys, young boys, when they’re forming their opinions about women. It was worrying that this kind of passage was out there.”

“The marketplace doesn’t test talent. It tests timing.”11 How many works have seen the light of day decades after the author (and her timing) were safely dead? How many writers had to flee hostile political regimes?

Mikhail Afanasyevich Bulgakov was a Ukrainian writer, medical doctor, and playwright is known for his novel The Master and Margarita, published posthumously, which has been called one of the masterpieces of the 20th century. Some of his works were banned by the Soviet government, and personally by Joseph Stalin, after it was decided by them that they ‘glorified emigration and White generals.’12

Anna Achmatova was one of the most significant poets of 20th century. She was shortlisted for the Nobel Prize in 1965, and received the second-most (three) nominations for the award the following year. Her work was condemned and censored by Stalinist authorities, and she is notable for choosing not to emigrate and remaining in the Soviet Union, acting as witness to the events around her.13

Iosif Aleksandrovich Brodsky was a Russian and American poet and essayist. Born in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg), Soviet Union, in 1940, Brodsky ran afoul of Soviet authorities and was expelled (‘strongly advised’ to emigrate) from the Soviet Union in 1972, settling in the United States with the help of W. H. Auden and other supporters.14

The internet is filled with advice on reading more.

I say, read better, more diverse—poetry, literature, fiction, short stories, research abstracts, and yes, footnotes! Read from different ages and writers of different ages.

A few years ago, I discovered I was reading crime/mystery fiction mostly written by American men. Mostly by accident by picking the best sellers. You know how it is, you’re in the library and look at the recent releases for names that resonate.

As a teen I used to love Agatha Christie’s detective novels, which I read serially at the beach. So I started researching crime/mystery fiction written by British women. Then I expanded to Irish, Scottish, European women. I reserve the books in advance online.

I’ve been delighted to discover many Australian, Canadian, and other women authors, too. For one, I find the plots are more interesting rooted in different cultures. Women also use more nuance in the story line.

Their endings are harder to guess, so a better challenge to my imagination. I also started reading the acknowledgment and historical notes along with bibliographies, which my father taught young me were important. The knowledge part.

But this is a story about how screens change us.

Thus we need to talk about Fiji. As Elena Rossini says, “What happened in Fiji with the arrival of television is a harbinger of the monumental changes that happened around the world with the introduction of smartphones and social platforms.”

I’ve been making a lot of content “for free” for a long time. When someone switches to paid—it feels like they’re excited to make a gesture of gratitude. I appreciate it like a nice big hug.

In English here. You will see Truffaut’s entry in the first batch.

“Ray Bradbury: Fahrenheit 451 Misinterpreted,” L.A. Times (2007)

“The mistake they made with the first one was to cast Julie Christie as both the revolutionary and the bored wife,” L.A. Times (2009)

“Ray Bradbury, The Art of Fiction No. 203,” The Paris Review (2010)

Quoted by Kingsley Amis in New Maps of Hell: A Survey of Science Fiction (1960)

“Conversations with Ray Bradbury,” Steven Louis Angelis, Florida State University (oh, the Irony!) (2003)

ALA documented 1,269 demands to censor library books and resources in 2022, the highest number of attempted book bans since ALA began compiling data about censorship in libraries more than 20 years ago.

Marche, Stephen, On Writing and Failure: Or, On the Peculiar Perseverance Required to Endure the Life of a Writer (Field Notes) (Biblioasis, 2023)

Mikahil Bulgakov was the topic of the first master class (Italian) Alessandro Barbero gave at Festival della Mente in 2022.

Anna Achmatova’s work was the topic of the second master class (italian) Alessandro Barbero gave at Festival della Mente in 2022.

Iosif Brodskij was the topic of the third master class (Italian) Alessandro Barbero gave at Festival della Mente in 2022.