How an engineering company defined 'value'

And how the answer changed since Aristotle's 4th C BC definition.

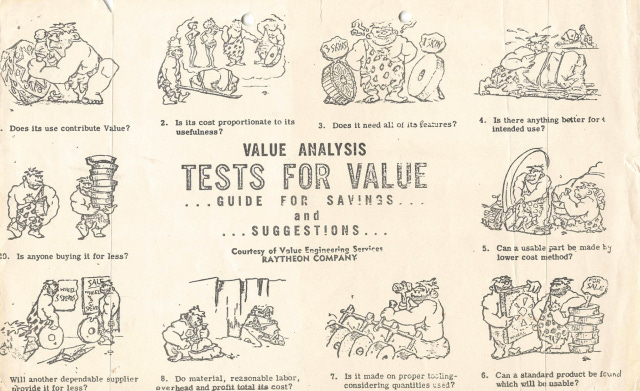

The Raytheon Company is a major U.S. defense contractor founded in 1922. In the 1950s, it began manufacturing transistors, including the CK722, priced and marketed to hobbyists. Was the one-pager below from around that time?

You may notice the list presupposes a shared understanding of the meaning of ‘value.’

Are the questions leading?

A lot on the value analysis list might seem like common sense. Then again, an entire lucrative management consulting industry built processes that should help companies answer these questions:

Does this contribute value?

Is its cost proportional to its usefulness?

Does it need all of its features?

Is there anything better for this intended use?

Can a usable part be made by a lower cost method?

Can a standard product be found which will be usable?

Is it made with proper tooling - considering quantities used?

Do material, reasonable labor, overhead, and profit total its costs?

Will another dependable supplier provide it for less?

Is anyone buying it for less?

Value engineering became a big movement in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The movement heralded a systematic method to improve the ‘value’ of goods or products and services by using an examination of function.

In the sequence the sheet presents, the questions seem to lead toward lean and ‘less is more.’

But the evolution of work seems to point in another direction.

Simple math in search of exponential growth

Quite often, when referring to ‘value’ today, people seem to be adding it. Research confirms that people favor adding over subtracting in problem solving.

An example of loss aversion? It’s literally the default. People don’t think about other options. Sunk-cost bias could be at play. Or perhaps a clue to the need for significance? I add, ergo I am. And companies may consider “adding” more creative. Subtracting just doesn't occur to people.

Adding has thus claimed a seat next to value in the modern psyche. Features, things, options, models, uses, size... everyone keeps adding and adding. And we lose sight of the value equation. Enlarging expectations, growing for the sake of growth, and so on.

We’re at the point where more is just more, without adding any value. In fact, a few things have run away from us, becoming unsustainable. Simple math in search of exponential growth gave us both, and that is not always a good thing.

Attention and incentives can help:

Adams and colleagues’ work points to a way of avoiding these pitfalls in the future — policymakers and organizational leaders could explicitly solicit and value proposals that reduce rather than add.

But the idea is not ‘less is more.’ Of course, nobody needs more of the things that are not useful, or valuable. We just need the right things at the right time.

To know right, figure out value

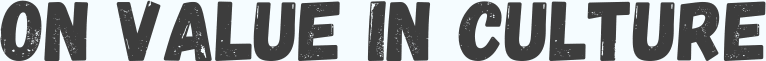

The test consists of reframing concepts (and words). What does value mean in different contexts? I found some useful definitions in a paper about value management for the construction industry.

Aristotle (4th century BC) distinguished between two meanings: ‘use-value’ and ‘exchange value.’ This is useful in industrial economics and manufacturing. But what's interesting is that ‘exchange value’ took off, and we overlooked ‘use-value.’

In the middle of the 18th Century, Adam Smith:

focused on “productive” activities that contributed to exchange value through the manufacturing and distribution of tangible goods.

And here’s where the exchange happens through money. Exchange value all the way down. You fix a price, the buyer needs to be willing to pay it.

In the last century, the focus has been on defining the ‘productive activities’ that create value for customers. Streamlining processes to increase profit has been part of the conversation. Hence the Raytheon Company one-pager.

But what about customers?

The context switches to consumer economics and marketing. You won’t be shocked to learn that there are different models and definitions. Value is more of a protagonist in service marketing. And here’s where it gets interesting: the value concept appears in relation to pricing.

Once again, we follow the money.

Price-based studies cite “... cognitive trade-off between perceptions of quality and sacrifice” and “benefit/cost ratio models.” The conversation is about perceived value and its proxies: low price; quality/price; what you get/what you sacrifice; what you want in a product/service. These read like a scale to me, from lower to higher perception.

Then there is the means-end theory.

If you try to understand value only by attributes like quality, worth, benefit, and utility you go down the rabbit hole of defining each alone—and in the situation in which you find them. The assumption is that people buy things only to achieve favorable ends.

But we know we’re on shaky ground here. Your ‘customer value hierarchy’ is likely unlike mine.

Finally, we get to multi-component/multi-dimensional models.

Where perceived value is made of several components. You may be familiar with these. Want, worth, need—where want is the esteem value, worth is the exchange value, and need is the utility value.

Another multi-dimensional model considers utilitarian and hedonic value. Utilitarian satisfies the rational, task-oriented, cognitive, instrumental and means-end related type of value. Hedonic describes the experimental and affective value, reflecting the entertainment and emotional worth of shopping.

There is something to be said for the experience. And you can design environments to provide that kind of value, as I explained in the connection between rituals and commerce.

Consumption value is actually 5 values: Functional, Social, Emotional, Epistemic, and Conditional. Most of these are fairly self-explanatory. You create epistemic value when your product has the ability to arouse curiosity, provide novelty, and/or satisfy a desire for knowledge. Conditional value depends on circumstances.

Holbrook’s dimensions of value is another multi-dimensional model: a) Extrinsic vs. intrinsic, b) Self-oriented vs. other-oriented, c) Active vs. reactive. This seems to be the most comprehensive of all the marketing models. It captures all economic, social, hedonic, and altruistic components of perceived value.

But it has limitations. Its complexity doesn’t include ethical and spiritual considerations. We are complex, ever-changing beings. Which is why the paper turns to psychology and sociology next. The context is spatial behavior:

The interaction models between individual and environment are gathering on analyses of social variables (individual and group, personality, culture, part, organization, social-economic environmental processing, sphere and frequencies characteristics) considering the influence of physical facts and variable’s analyses of nature and shaped environment (characteristics of architecture and landscape, characteristics of the processes).

As we’re rethinking the role of the office in business context, this part could be instructive. For example, the role of objects in our space and what they enable or prevent.

Make it possible to make high value work

“What you don’t know about women is a lot” is a line Olympia Dukakis delivers to perfection (2:21) in a restaurant scene of Moonstruck. (Every man needs a speech from Dukakis.)

It’s fitting with the study on “The Concept of Value for Owners and Users of Buildings” because it followed a progression from most materialistic to most nuanced. We’re square in the nuance space there.

The study left out value in ethics. So, I looked it up:

In ethics, value denotes the degree of importance of some thing or action, with the aim of determining what actions are best to do or what way is best to live, or to describe the significance of different actions.

Today, we refer to this meaning by using the word values.

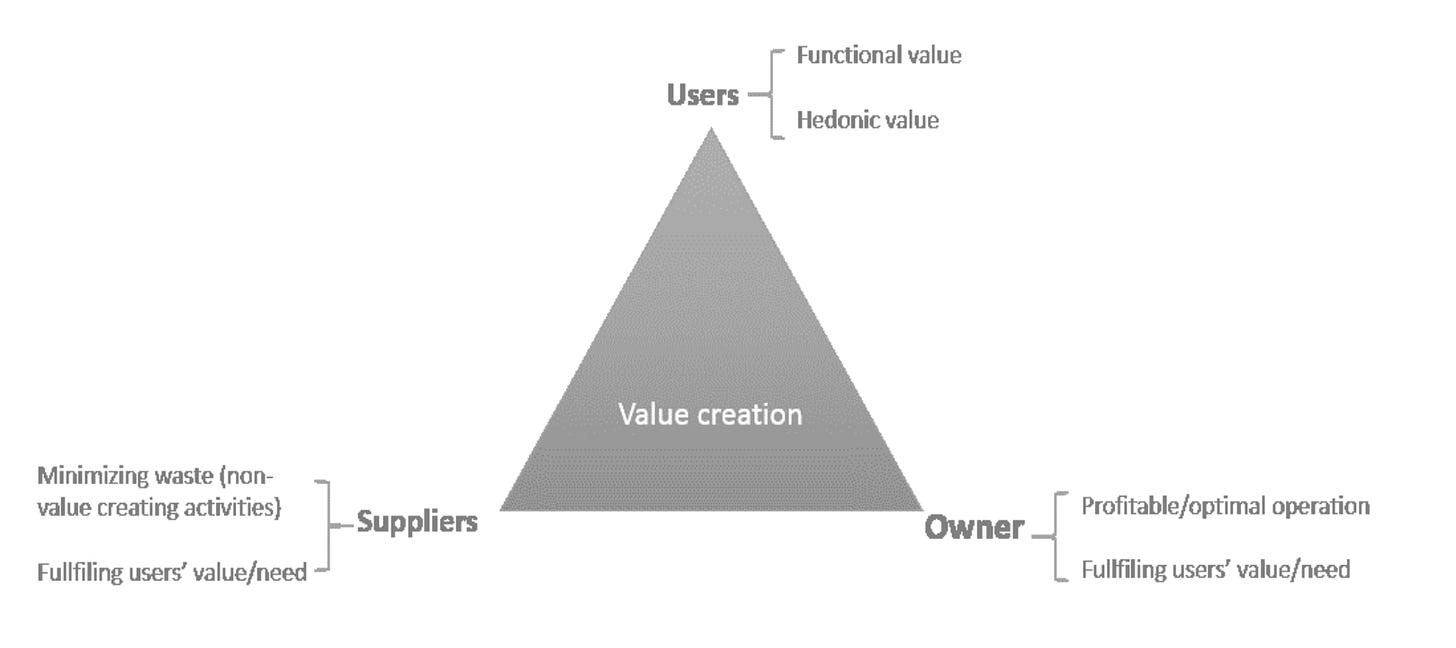

Legendary coach John Wooden has talked eloquently about values. Faith and patience are the virtues that hold his system of thinking together. Enthusiasm is a values cornerstone, along with industriousness. He makes the case for aligning value and values.

Values spread through culture. I wonder what percentage absorption happens through example vs. through one-pagers and notes. My hunch says mostly through example—watching what the boss, parent, peer, community, etc. does—and practice.

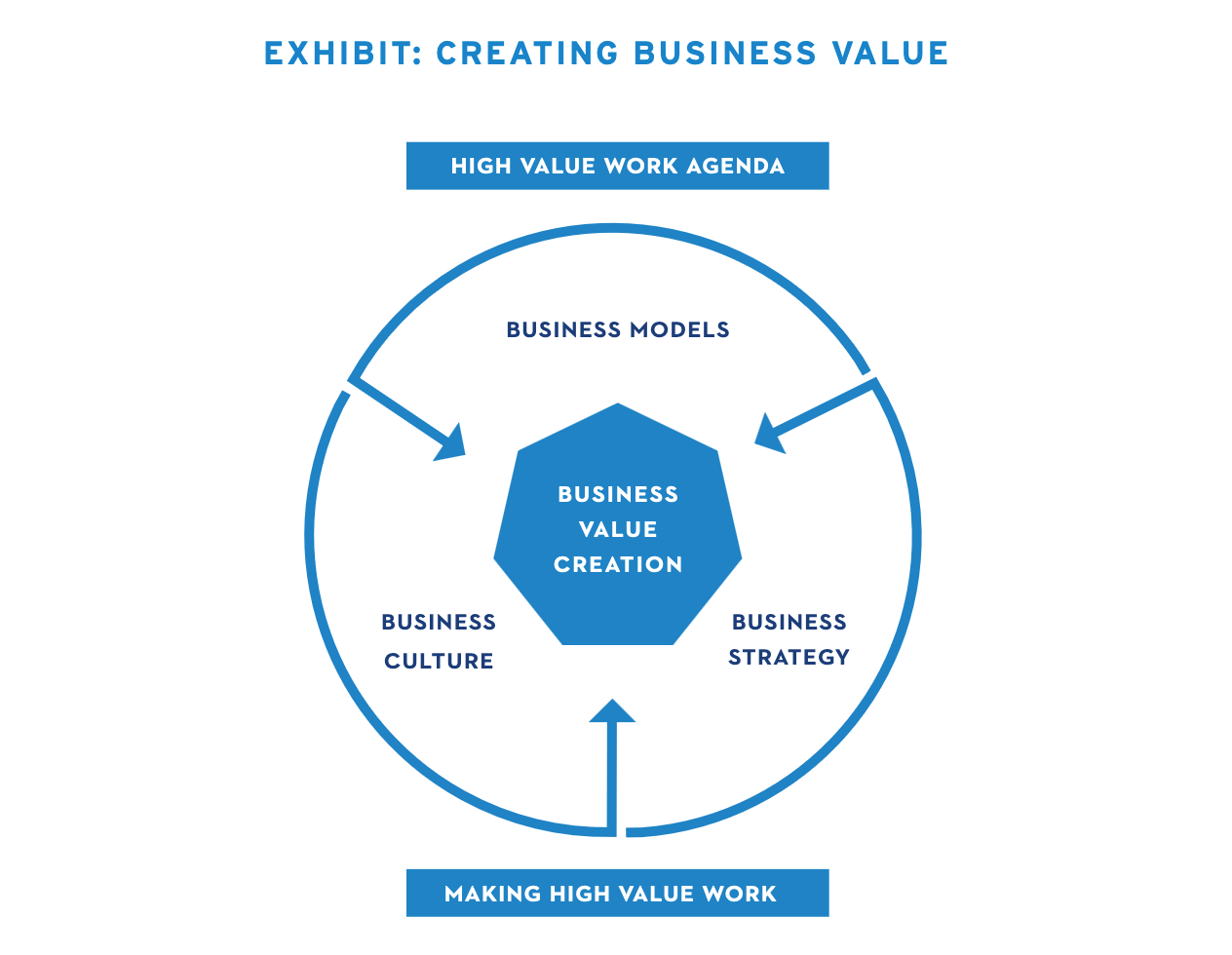

A few years ago, The Futures Company created a report on Making High Value Work for the Association for Finnish Work.

They propose that companies can use five practices to build high value cultures:

1. One Step Beyond (business context, external challenges)

2. Running Towards the Problem (business context, external challenges)

3. Human Centered (design, run the business in the smartest, most inclusive way)

4. Lean in the Right Places (design, run the business in the smartest, most inclusive way)

5. Living the Story (communicate a distinctive purpose and identity inside/outside)

The fifth practice is also an active agent in making the other four happen. So we have the conversation agent, the levers, but still an imprecise grasp on the concept of value. “I know it when I see it” is not quite helpful here.

My work is mostly in and around the fifth practice. But it touches all five. So what about use-value? I keep going back to the relationship between energy, value, and work.

Tests for value

So far, I’ve touched upon several qualitative and otherwise complex paths to measuring value.

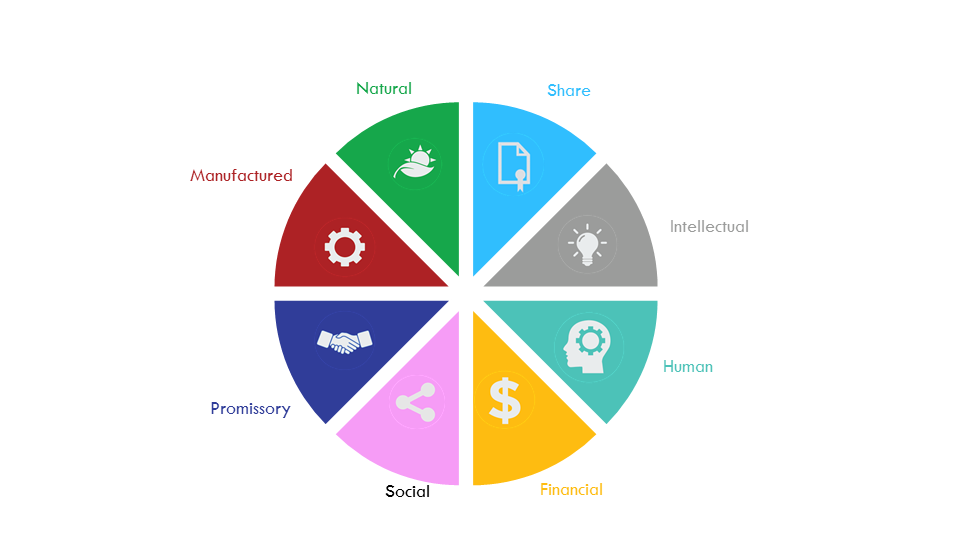

But what if there was a quantitative path? Peter Tunjic and I have been discussing a more objective method to evaluate value. For example, the reason why to build a company is a worthy endeavor. TL; DR: to capitalize on the value of many capitals.

The problem with converting to or measuring everything with money is:

money can’t buy love. This is just another way of saying money can’t be transformed into all forms of capital. A subjective theory of value that uses money as the measure of equivalence was a dead end.

What do all forms of capital have in common? Was the next step in Peter’s research.

It led to the idea that value is energy in its social form.

At its most basic, value is equality of a form of a capital to do work. For example, I can use my financial capital and pay someone to walk my dog or I could use my social capital and ask a neighbor. Either way, Sooty gets walked.

From here came the work on Capital Dynamics: the relationship between value, work, the forms of capital in which value accumulates, the entropic and other qualities of each form of capital, and the conversion of value between different forms.

Here’s the thought process in more detail (I took notes as we talked, any mistakes are mine):

Value is a quantitative property of a capital that is transferred to perform work or bring about change.

Value accumulates and is stored in various capitals.

The amount of value stored in a given capital is dependent upon the unique properties of that capital.

Value can be exchanged between capitals (though not all capitals are interchangeable).

Value is created or lost when one form of capital is exchanged, transformed or converted into another form of capital.

Capitals do no spontaneously change form. Business systems (prime movers) must be interposed between capitals

The processes of transforming capitals involve transaction costs.

Business models are prime movers.

Thus, the properties that bring about positive change form the core concept of value. Rather than being a subjective thing, value can be tested. Reliable tests for value will include the right capitals and engines.

How do you define value in culture?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On Value in Culture with Valeria Maltoni to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.