Why the Curious will Win by Having a Universal Gaze

How I learned to stop worrying about terrible behaviors.

Everywhere we go, there we are. And nowhere that is in more obvious than when we travel. We get out of our usual routine (habits or rut, it depends on your outlook), and come into contact with ‘the other’—person and/or place.

Whether we bump into stuff, or integrate with it is up to us.

With social media, it’s all too easy to feel unencumbered by the past, to see only the ever-now. But we have it all backwards. It’s only when we can see more broadly that we start to appreciate the present.

On Value in Culture is a reader-supported guide to the role of narrative, language, and art in how we organize, perceive, and communicate about reality. Support my work with a paid subscription.

I’m just back from a long trip to the south of Italy. After 20 years of travel, I was not prepared to face the culture shock. I was born and raised in the North. Back then, the issue of migration was people from the south in search of opportunity.

There was a subtle, insidious prejudice in society, it’s still there in many ways. I was part of that, though unaware of my biases and assumptions. Then at some point during high school, our parents decided to go to Calabria on summer holiday.

After an 11-hour drive, we found a splendid, simpler place (if partially built) in Tropea, Capo Vaticano. The food was amazing, the white sandy beaches free, the company fun. So why didn’t I return to explore the south until this year?

Because I has learned too little about the past. And mostly about the past immediately around me.

Naples, Caserta, Apulia (Puglia) were part of this trip. But they were not just an itinerary, they were destinations—places where to soak up everything, meet as many local people as possible, learn the culture.

I was surprised at every turn at how much I had overlooked. Naples and Bari had the most cultural impact on me. You’ll have to discover for yourself, or become a founding supporter to get the full enchilada—with detailed itineraries.

My big ah-ha was that to see better the present, one has to dig far into the past. The Bourbon Tunnel in Naples—when you become disoriented you see more clearly—and St. Nicholas days in Bari—the power of rituals—are a good start.

Brindisi’s history was a total surprise. I learned a lot from our host whose grandfather was involved in the commercial route from London to Delhi. And about the wars and what happened there, or elsewhere (the crusaders left from its port.)

Here’s the important bit, speak to the locals. I know I have the home advantage here—I speak the language. But when you make the effort, you meet kind people happy to help you figure out stuff, get oriented.

I had history lessons from the taxi driver who took us to the train station. He even recommended a book, which I shall read even as I learned about its limitations. All the while, he kept the meter running in front of the station to finish the story. That’s Naples for you, and I say it with the utmost (newfound) respect. The art of negotiation.

These people have been through a lot over the centuries. Wars, fights, from poverty to splendor—the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, Maradona—to scraping for their livelihood. They’re ready for anything. It rains, they have umbrellas and ponchos to sell.

And in Naples, when it rains it pours. Imagine 15,000 people descending on the city from cruise ships every week in high season. And that’s only on Fridays. It’s high season most of the year.

Yet these are strong people. Time and time again, they find new ways to make life work—with the accent on ‘life.’ But try to stay away from the online hype. I had my worst pizza in Naples because I believed the articles (Google doesn’t know Naples.)

Instead, watch where the locals go. It may be out of the way. Tourists are not always on their best behavior—especially when it comes to trash, physical and metaphorical. So it’s a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy—we get what we give to a place.

In Naples, I recommend a restaurant that opened only June 2023, Pulcinella Bistro’. Giorgia from our inn eats there. I can attest to what they say about the quality of their ingredients, we ate there three times. Do try the local Aglianico red.

Back in Naples upon the return leg of our trip, the taxi driver who took us to the airport told us people live with little in the city—it’s a marvelous place to be, he said. Of course, he also complained about Uber taking business away from taxis.

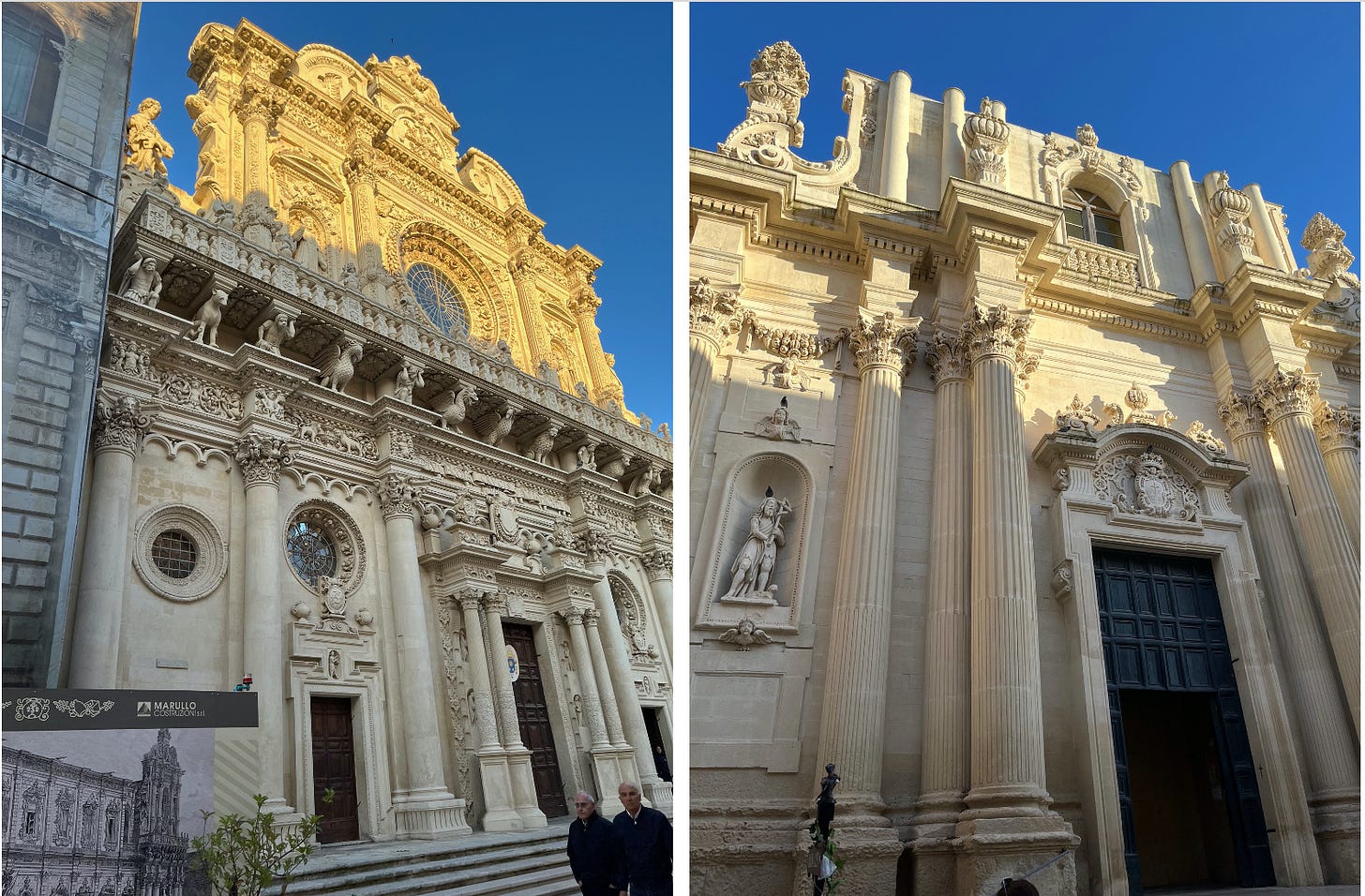

Lecce is one Baroque church after the other—each more splendid than the next. People in the south frequent churches more than in the north. Different history and influences (e.g., Papal state.)

One evening I listened to a sermon outside a church in old Bari—standing room only inside, speakers outside for those with kids in strollers. I’m a lapsed Catholic, but it was a magical experience—communal, in the broadest sense of the term.

The trains were another cultural surprise. Though there are fewer than in the north (at some point they stop altogether—we saw abandoned train stations throughout the Salento area), they were on time, cleaner, and less noisy than in the north.

There were also fewer tourists on trains. Perhaps car rental for the duration is the way most go. Because these cities—Bari, Brindisi, Lecce—were literally besieged. If you want to meet people from all over the world, go to Naples and Apulia.

I could not live in a place like that. Where hordes of people descend on the city daily and leave stuff in their wake (physical and emotional.) Yet, our hosts seemed to take things in stride.

We got to Lecce by train the day of the official Anniversary of Italy’s liberation (WWII)—April 25. It was mayhem. People everywhere. The energy from locals was palpable, even as they commingled with groups that followed the umbrella/flag around the city.

Why the curious will win

If I’m honest, the crowds bothered me a lot at first.1 It was the first time I traveled to places filled with tourists (and it was ‘low’ season.) But after I talked to a few local people, I forgot all about them and went about my business (as they do.)

While leading with what I wanted to do got me anxious, the connection and conversations with locals engaged my curiosity. It had a calming effect. And when I relaxed and accepted what was, time expanded.

As we’re actively interested and want to know more about something, we become more open to unfamiliar experiences. Which means we create greater opportunities to experience discovery, joy, and delight even in everyday chores.

Researchers at UC Davis Center for Neuroscience have found that piquing our curiosity changes our brains. Investigators found that it increases activity in the brain circuit related to reward.

“Curiosity may put the brain in a state that allows it to learn and retain any kind of information, like a vortex that sucks in what you are motivated to learn, and also everything around it. We showed that intrinsic motivation actually recruits some of the same brain areas that are heavily involved in tangible, extrinsic motivation.”

Matthias Gruber, a postdoctoral researcher

When we’re curious, we see things differently, we become more observant and immersed in the present moment. That’s because it engages our intrinsic motivation, even affects memory, which is why everything seems to be more vivid.

I did much better when I shifted my perspective from that of someone who lives in one of the places I visited.

Philosopher Ilaria Gaspari says that “Many past events have taught me that culture is a very male-dominated sector.”2 There’s still an assumption that women don’t have a universal gaze.

Yet, everyone wonders about human desires in ways big and small.

Backpack ‘off’ when you board a plane

Or a bus (or a country.) I say that figuratively and literally—what you carry on your back ends up slammed in someone’s face. And that’s not a good way to start a conversation. (People do turn and forget they have it there. Some are really heavy.)

Replace assumptions and whatever weighs you down with curiosity, instead. Take for example the question: How could I have a more fulfilled life? Every person I’ve met thinks about that—maybe not in the exact words.

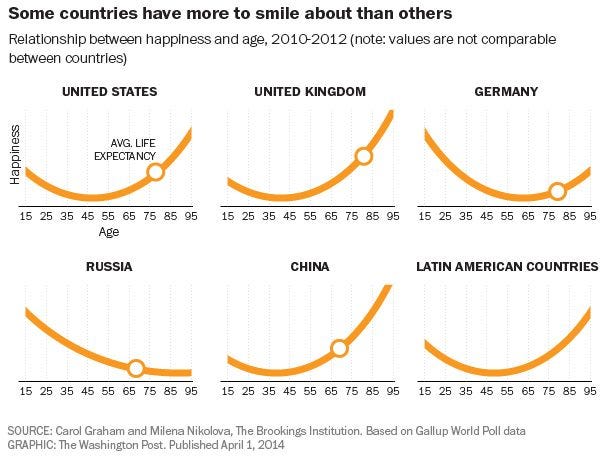

People are complex beings. If you conduct any form of customer research, you’ll see how it’s not a straight line. It’s more like a curve that dips in middle age—circa 35-40+ years of age—then smiles again.

When you find and own your worldview, that’s when you start on the satisfied side of life curve. A process by elimination—labor limae, the filing work every artist performs after sketching the work (writers included.)

Companies work along a similar curve and process, but many don’t make it to middle age. Which is a shame, because the best from there is typically yet to come.

You wouldn't tie apples to a dead tree

Yet, companies are tempted to operate this way. They come up with fancy mission, vision, and value statements that try to dictate how people should operate to attain a position (fruit) that comes from lessons (seeds) that have not been planted in those same companies.

They may sneak this ‘fraudulent fruit’ into first impressions with prospects and employee interviews without a second thought. But they it all comes to light in due time with customers and employees (the people who matter to business health, long term.)

I used a similar concept to illustrate the difference between flash-in-the-pan and long-lived ideas. It’s a perfect illustration of how culture works. Quality products and results still come from quality thinking, doing—and commitment.

Thus, culture is the byproduct of consistent behavior.

Many things contribute to culture that have become invisible in modern-day accounting. So we leave a lot of value on the table.

The cities and towns I visited have been there for a very long time. In some cases, as in the Salento area, which is the heel proper piece of the boot, the Greeks and the Ottoman armies came in and left signs of their culture—along with a wake of death.

As the great synthesizers they were, the Romans integrated everything. So much so, that a Greek theater that was built in Lecce is now called a Roman theater.

We got this bit from a young man who returned to his native city after living in Trentino. Our paths crossed by chance at a construction site in the old city. He explained how anywhere you dig in old parts of Italy, you may find layers of artifacts. But I love that they build with them as part of the new iteration.

Culture has power over our behaviors. And the people in the south have learned to go with the flow.

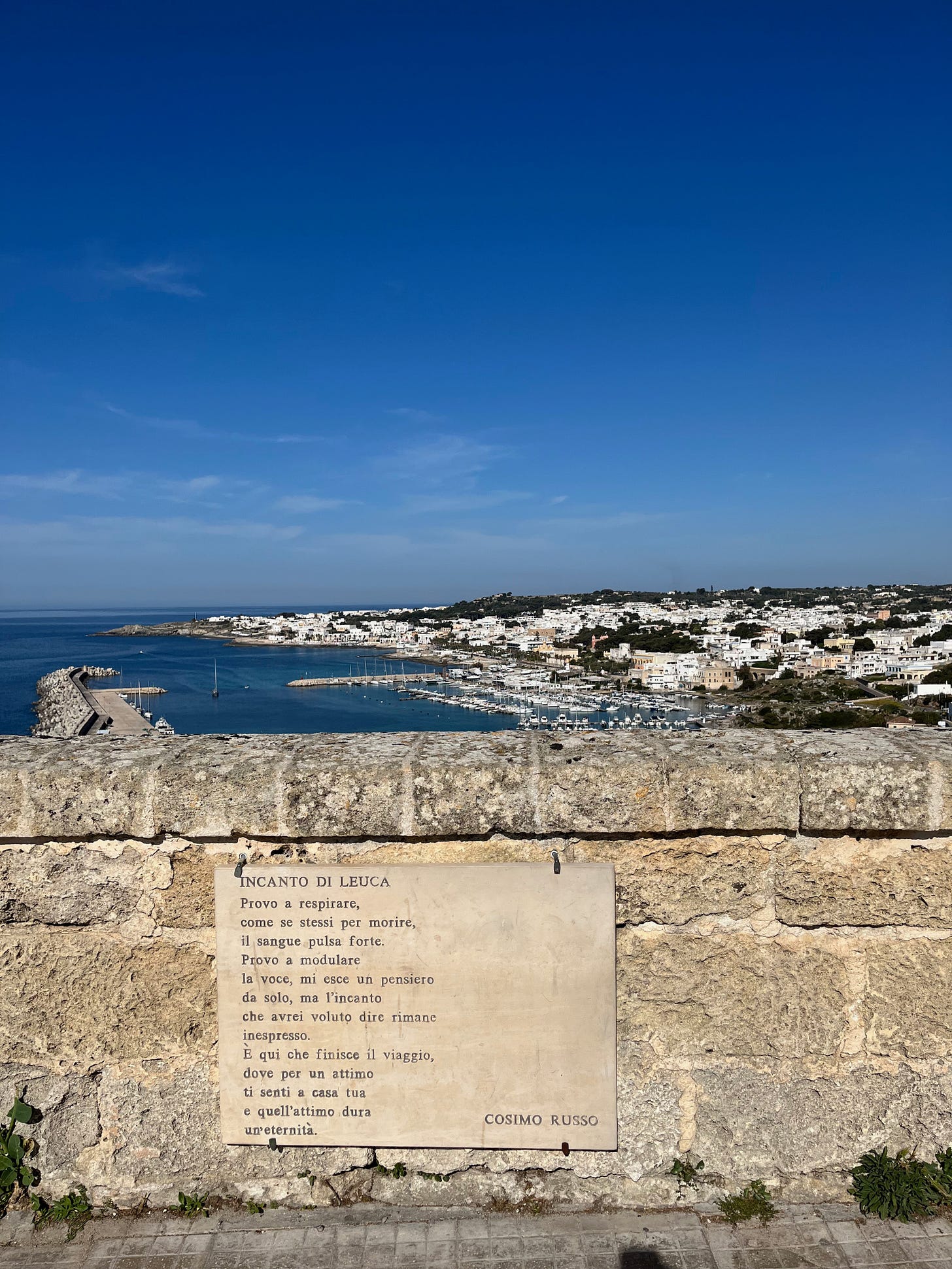

De finibus terrae is the end of the earth

That’s what you find on top of a promontory in Santa Maria di Leuca—the very tip of the heel in Italy. A quiet town of 1,000 people who don’t even have to lock their doors at night in the winter, it adds 30-40,000 people in the summer.

While we traveled to Otranto on the Adriatic coast—a jewel of a town with a dark past: 600 young men lost their heads when they refused to convert to Islam in 1408—Gallipoli, Santa Caterina, and Nardo’ on the Ionian side, Santa Maria di Leuca was our ultimate destination.

(We also went north to Alberobello to see the Trulli and Ostuni, the white city, where we got a parking ticket—and an opportunity to get help at the post office to pay it. Everyone was super nice about it.)

Santa Maria di Leuca is where the Adriatic and the Ionian seas meet—a mix of currents, winds, and cultures. You can see the very end of Italy. It looks like an alligator from a certain perspective. It’s not possible to take one step further on earth.

My sister’s final resting place. She had chosen it as the place for her retirement. Now, instead of just being in a house, she’s everywhere. And us with her for one glorious day of guided exploration.

And to think that we almost blew off the unassuming guy who asked us if we wanted to see the caves on the sea. Our culture has become so saturated with sales pitches that we’re on guard even with the things we want to do.

(I instituted a new policy for my email address. Any random solicitation I receive gets a free subscription to On Value in Culture. There are better pathways to value.)

‘At the end of the day’ is an overused expression in business, probably because it expresses a universal—the end point. I’ve learned to stop worrying about terrible behaviors and to make the most out of encounters—we never know our ends.

This to me is what it means to have a universal gaze.

Leuca Enchantment

I try to breathe

as if I were about to die,

the blood pulsates strongly.

I try to modulate

the voice, a thought comes to me

unbidden, but the enchantment

which I would have liked to say remains

unexpressed.

This is where the journey ends,

where for a moment

you feel at home

and this moment lasts

an eternity.

References:

Kabat-Zinn, Jon, Wherever You Go, There You Are (Hachette Books; 10th edition, 2005)

See also, how ‘revenge’ killed travel for a commentary on the close-minded attitude that many take to other places—the people who live there are ‘other’ in their eyes.

From a 2020 interview in Rolling Stone, ‘Ilaria Gaspari è l’astro nascente della filosofia italiana’ (Ilaria Gaspari is the rising star of Italian philosophy.)