What you can Learn from Dante's Inferno and its 9 Circles

He wrote the book in 1307—his exploration of human themes still applies more than 700 tears later.

I consider myself fortunate to have had the opportunity to read each of the books in the Divina Commedia1 several times over with famous researchers and scholars. Dante’s is by far the trilogy I’d take with me anywhere.

The story of how Inferno formed is relevant right now.

This is how it went down. One day, Lucifer—once one of the most beautiful angels in the firmament (maybe except this part)—leads a revolt against God driven by pride. The revolt fails miserably and this angel, now damned, is thrown down from heaven.

Falling to Earth, the ground is so horrified that it moves aside. An immense chasm opens up which will be Hell, Inferno. Dante’s analysis of human themes here is the scariest.

Strap in, this will be quite the adventure.

Reminder: You can get extra insights—in-depth information, ideas, and interviews on the value of culture.

Join the premium list to access new series, topic break-downs, and The Vault.

The chasm in which the Inferno of the Divine Comedy is located is not merely a ditch. It’s an entire underground world with its own precise geography that Dante, canto after canto, describes in detail.

Dante Alighieri was a man of his time—a Catholic of minor nobility status in 13th-century Italy living in the shadow of the Crusades. This influenced his viewpoint and how he wrote his masterpiece.

The poet envisioned Inferno as nine concentric circles, each designated for a specific category of sinner.

As one descends, the sins become progressively more serious, starting with the sins of incontinence (lust, gluttony, greed, and anger) in the higher circles and ending with the sins of heresy, violence, fraud (a grave sin indeed), and treason in the lower circles.

Jerusalem is the city that provides access to Inferno—there’s a door with a threatening inscription carved above it. The inscription in first person adds a frightful sense of solemnity and mystery, as though it literally speaks for itself.

It’s the single most powerful statement in the book. One that clarifies the finality and importance of the place.

(Paraphrased by me)

Through this door, you’re entering a place of sorrow, eternal pain, and lost people. Justice, Power, Wisdom, and Love are the powerful virtues that made this place. The irony is that the people here perverted all of them, in one way or another. I’m an eternal place, and all things here are eternal. Abandon all hope when you enter.

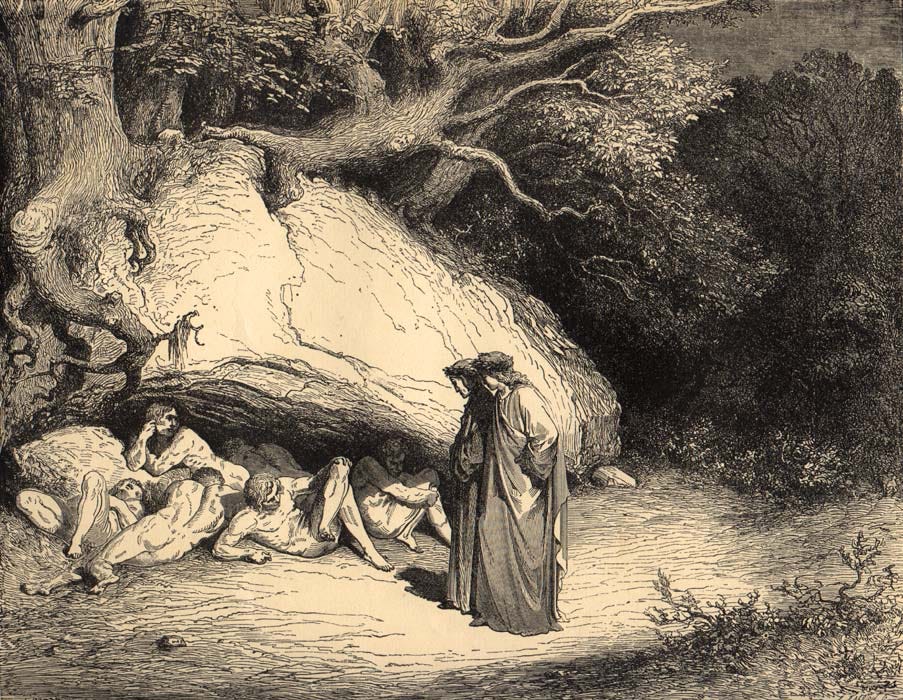

After the door, an area called Anteinferno opens up where the ignavi2 are found, that is, the souls of those who sat on their hands in life. In the case of the Divine Comedy, we are not referring so much to physical activity as to social laziness.

Dante was the first writer to openly denounce indifference. But others followed.3

However, today, we seem to have reached a real reversal of the problem. An army of sofa partisans and professional activists have replaced the indifferent. With social media, everyone has the obligation to have an instant opinion on everything.

In a world divided between followers and haters, it is increasingly difficult to be neutral. We’re thus equipped to reach the comfort of indifference, without losing the purity of partisanship.

Today we have the survival of sins and the disappearance of sinners.

The obligation to take a stand has annihilated the power of doubt. The duty to take a stand ‘for’ or ‘against’ has flattened complexities. To choose a flag to fight under without ‘ifs’ or ‘buts’ may create the opposite effect—it nullifies the power of critical distance and encourages intolerance.

Perhaps we need the indifferent after all, because seemingly today no one stands in front of the gates of hell.

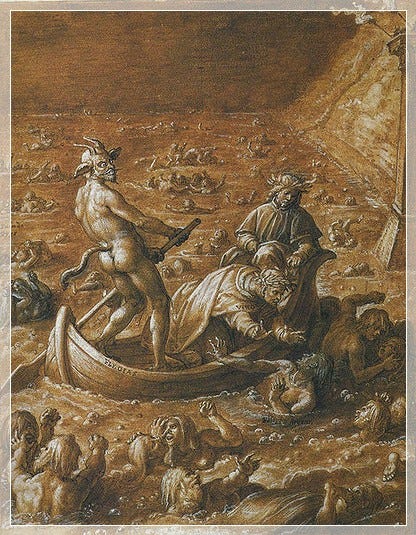

After the gates with the inscription, we come to a river—the Acheron—where Charon the ferryman takes the souls of the damned to the opposite bank on his boat. Here we find the first of the nine circles.

1. Limbo

Limbo was born to answer a problem that ordinary people felt, which is also why the Purgatory was born (recent invention in Dante’s time.) Where do the souls of those who could not free themselves from original sin in time—through baptism—go?

This is the place where those who have never known Christ exist and it’s split into two locations. On one side is the Limbo of infants and of the anonymous crowd of men and women lacking the objective conditions necessary for salvation.

On the other is the Limbo of the illustrious (Limbus famae.) Illustrious for various titles and merits, listed almost haphazardly according to the reconciliation or fusion of different systems or beliefs typical of medieval culture. They’re characters of various origins—many already named in the Aeneid—and true wise men.

It’s a crowded place.

Philosophers, poets, doctors, astronomers, commanders (Dante meets Julius Caesar), heroes. All the great souls of the ancient world are here—the megalopsychoi (Greek), the magnanimous (Latin.) Plato, Seneca, Thales, Anaxagoras, Democritus, Empedocles are among them. Dante meets Aristotle and Socrates.

The ancient poets who welcome Dante into their circle are Homer, Horace, Ovid, and Lucan who, with Virgil, represent a literary ideal and a model to refer to.

As he describes the scenes, his tone is serious and the melancholic. A nearly humble mood allows us to delve into the intimacy of Dante’s thought as he asks himself what is the purpose of wisdom and study, of poetry and philosophy.

While the ignavi are insipid souls, the souls in limbo are good, magnanimous, even great. They’ve done the most they could in their lives. They’re sad, but don’t suffer; theyre at peace, but aren’t happy; they sigh, but they’re calm in their state of apparent imperturbability.

At this point, we leave the company of these learned humans to descend into the Inferno proper.

2. Lust

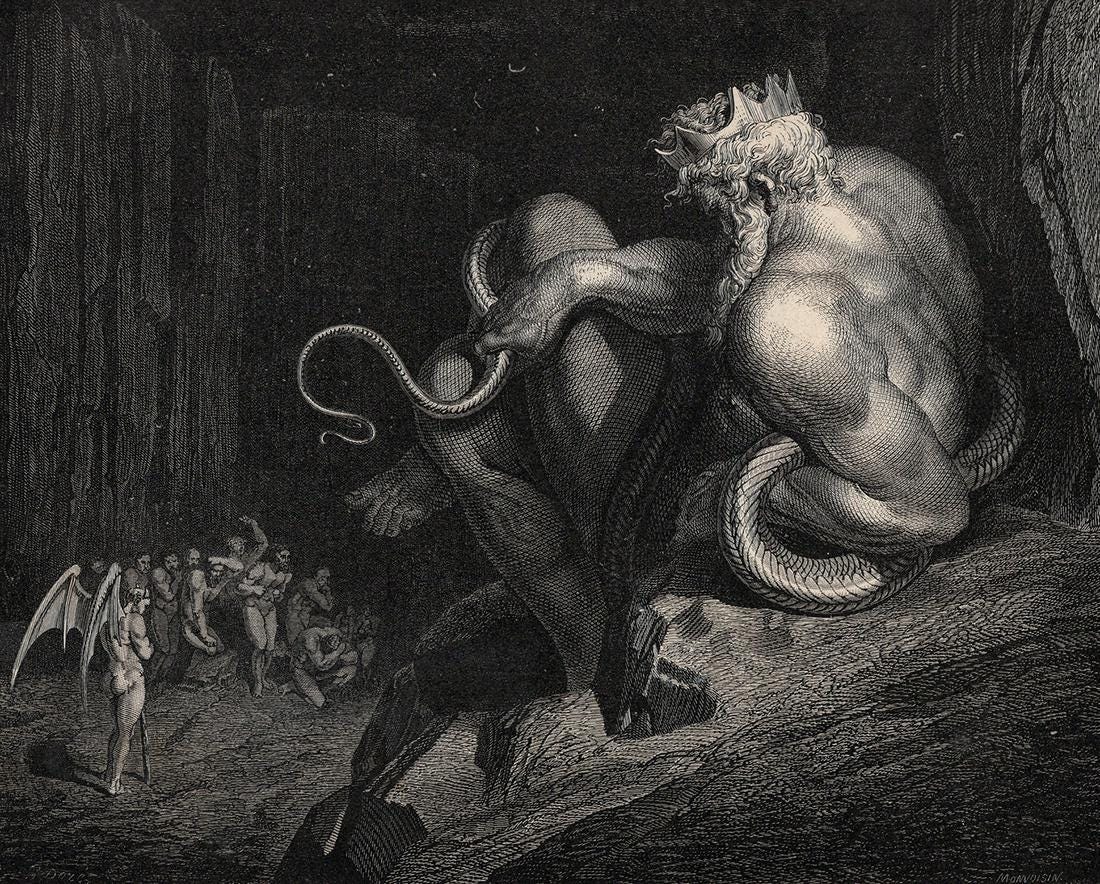

The Second Circle is where Hell itself begins. Here a monstrous character makes his appearance—Minos. After describing his role, the scene shifts to the punishment of the lustful, tormented by a relentless storm.

Damned souls are terrified by Minos' appearance and by his judgment.

Minos only needs to look at them to know what punishment to inflict. He communicates his sentence by rolling his tail as many times as the circles of Hell to which the soul is destined.

There’s no light, the air is dark and shaken by a very strong storm of wind to toss and beat the souls of the damned. The wind represents lack of lucidity and order, the absence of rationality and the abandonment of the body to instincts and sexual passion.

In this storm, souls do not wander haphazardly but are divided into groups based on the type of love they had. The group that attracts Dante’s attention is that of those damned who died for love.

Among them are two lovers who, unlike the others, are shaken by the storm while remaining embraced and firm to each other. They’re the souls of Paolo Malatesta and Francesca da Rimini who remind us of Lancelot and Guinevere.

We could say the two are crime news of his time, contemporary history. They’re in-laws killed by her husband (and therefore by his brother) only a few years before Dante’s descent into Hell.

Gianciotto Malatesta, the killer, is still alive. But the area of Hell called Caina—one of the four areas of Dante’s ninth circle—awaits his death to welcome him and make him serve his sentence.

Other souls Dante meets here are those of Achilles, Paris, Tristan, Cleopatra, and Dido.

3. Gluttony

Dante and Virgil then descend into the third circle where there are the gluttons, tormented by an incessant rain of cold and dirty water, snow and hail. The rain mixes with the ground, creating a disgusting, smelly mud.

The guardian of this place is Cerberus, a character from pagan mythology who has the appearance of a three-headed dog—a gigantic and bloodthirsty mastiff whose terrible barking echoes in the air, deafening the spirits.

Here Dante meets ordinary people. Sinners lie supine in the stinking mud, under a rain of hail, filthy water and snow, and are deafened by the barking of Cerberus as he greedily tears them apart.

As in life they indulged their gluttony too much, loving refined and fragrant food and drink, so now they’re forced to satiate themselves with a filthy and stinking filth. Because they ate greedily, breaking the food, now they are greedily torn to pieces by Cerberus.

From the mud rises the figure of the Florentine Ciacco, with whom Dante begins a long conversation on the political events of the city. Ciacco prophesies the outbreak of civil war and the bloody alternation of power between the White Guelphs and the Black Guelphs.

Politics and ethics intertwine in their conversation. Giovanni Boccaccio later incorporated Ciacco into his 14th-century collection of short stories, The Decameron.

4. Greed

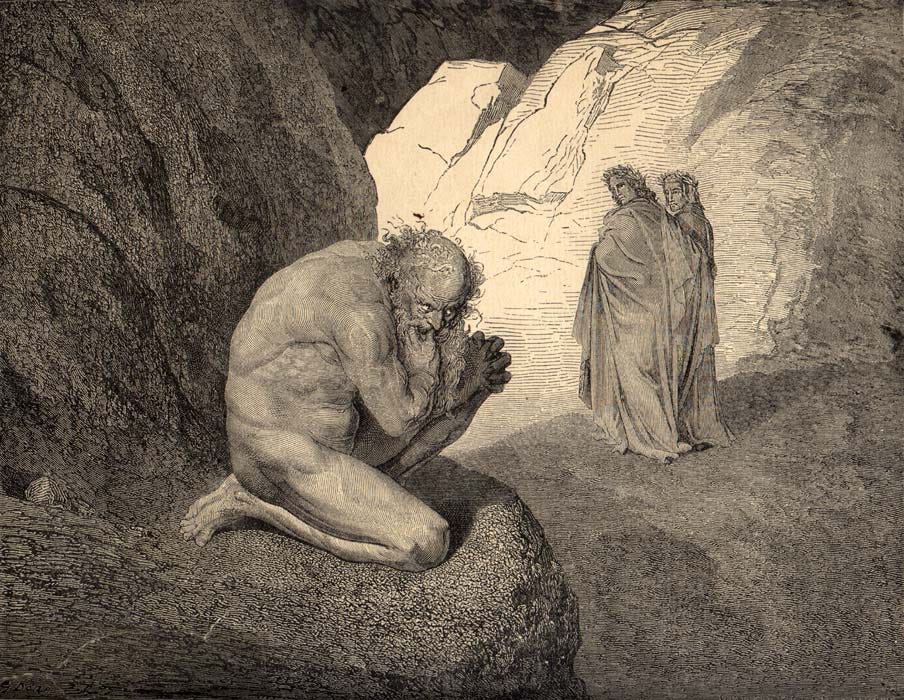

“Papé Satàn, papé Satàn aleppe!” Pluto began to shout with a hoarse voice with words that have no meaning referable to a human language. An example of the incomprehensible language of the devils, a sound devoid of any meaning, the expression of a confused and brutalized mind.

Pluto, the circle’s guardian, is the the mythological king of the Underworld. Here Dante meets more ordinary people. This circle is reserved for people who have hoarded or squandered their money.

The damned push enormous weights with their chests around the edge of the circle. They’re divided into two groups—the avaricious travel their half of the circle in one direction, the prodigal in the opposite direction.

In life these sinners toiled to accumulate or squander riches for the love of money and luxury. Now they’ll toil for eternity to push with their chests boulders of different sizes, the size of which varies according to the quantity of goods accumulated or squandered.

When avaricious and prodigal meet, they reproach each other for their guilt. Many are men of the Church, but Dante cannot recognize them because their guilt has deformed them to the point of making them unrecognizable.

Dante and Virgil don’t interact directly with any of the circle’s inhabitants. This is the first time they pass through without speaking to anyone—a commentary on Dante’s view of greed as a high sin indeed.

5. Anger

After they get around Pluto, the two poets arrive on the banks of a river called Styx. In the fifth circle, a moat of dark waters boils that forms the Styx swamp, where naked and mud-stained people are immersed.

They all appear angry and are intent on hitting and biting each other ferociously. Just as in life the wrathful attacked others with their words and their blows, now they are forced to hit and bite each other for eternity in a disgusting mud.

In the midst of them, but completely buried in the muddy water, are the slothful, those who outwardly restrained their anger, clenching their grudges within themselves. They sigh deeply continually, as can be seen from the boiling of the swampy water.

Flames appear on top of a high tower, to which another flame responds in the distance, like an alarm. They’re signals that the devils exchange to call one of them who’s arriving, very quickly, on a boat, already threatening from afar.

It’s Phlegyas. Virgil addresses him harshly and forces him to take them on board. Halfway across the ford, a sinner tries to attack the boat, but Dante, recognizing him as Filippo Argenti, an angry and violent Florentine (Black Guelph), repels him.

Immediately the souls of the other damned hurl themselves upon him and torment him. The wrathful, who in life beat and tore others, now beat and bite each other; the slothful, who in life did not know how to free their anger and kept it buried within, are now immersed in the boggy ground and have neither free speech nor free sight.

Dante and Virgil are then threatened by the Furies when they attempt to enter through the walls of Dis (Satan), the deepest hell, from which flashes of fire project. A messenger from heaven intervenes to allow the two poets to enter the city.

This is a further progression in Dante’s assessment of the nature of sin. The poet begins to question himself and his life, realizing that his actions and nature could lead to this lifelong torture.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On Value in Culture with Valeria Maltoni to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.