Panettone

The true story of the Italian Christmas cake, from simple origins and legends to cult dessert.

I don’t know about you, but I could use a sweet story with a surprising twist as the year wraps. There are reasons to be cheerful, to appreciate reality and its difficulties, but also the value of resistance to doom and gloom.

This is my last post before the holidays—see you all in the new year!

Two decades ago, I could hardly find panettone anywhere in my neck of the woods—even in New York city. Things have changed. Over the last decade, the panettone craze has taken hold in many parts of America.

To give you an idea of the scope, Brazil1 produces and sells 200 million per year.2 Peru, where they eat panettone year-around, comes in second.3 Italy is (only) third in the world at 50 million—around 10 million shy of one per citizen.

Since 2017, sales have gone up also in the U.S. In fact, if you wait to order, by November you’ll have a hard time finding the most popular brands. Sicily’s Fiasconaro, Veronese Borsari, Vicenza’s Filippi, and some of the Milanese.

The use of natural yeast and high-quality ingredients sets these products apart. In addition to natural yeast, I personally favor the vegan versions, made with extra-virgin olive oil (EVOO.)

Trader Joe’s now stocks a small one (3.5 oz), and the over 1 lb. This year, I also saw a chocolate chip version. Those who’ve compared the list of ingredients say Ferrara is the company that makes it4—excellent for French toast.

Last year, the turnover of panettone exports worldwide reached nearly 525 million dollars. Within that number, the share of artisanal versions has grown (recipe for the brave at the bottom.) There are many stories tied to the rise of panettone.

Reminder: You can support my work and get extra insights—in-depth series, ideas borrowed from other countries, and interviews on the value of culture.

Join the premium list to access new series, topic break-downs, and The Vault.

Three engineers and a marketing pro get together to make panettone—it almost reads like the premise of a bar joke, doesn’t it? Before I tell you the story, though, I’d like to ask you—pretty please, not to call it a fruitcake (I saw that somewhere online.)

Perhaps the work of artificial intelligence (AI.) Because any sane person who’s even seen the Italian Christmas delight would be hard-pressed to confuse Milan’s soft cake with the spicy loaf brought to us by ancient Rome.5

Panettone has become the must-have Christmas dessert on Italian tables—from the Alps to the coasts of Sicily. And increasingly around the world. But to understand the fortunes of a dessert born in the Milanese fog fully, we need to know its history.

Legend has it that panettone was created by mistake during Ludovico il Moro’s Christmas lunch. The cook forgot the cake in the oven, so it burned. Scullery boy Toni, then combined what he could salvage with butter, raisins and candied fruit

Et voila’— ‘Pan di Toni,’ which later became panettone. Maybe.

Or maybe the reality is a bit more pedestrian. Those who look closely also find that it’s much older. Panettone means ‘large bread’ and falls into the category of late medieval sweet Christmas breads.

Dark age it was not, though sugar at the time was a luxury good. They used it only to sweeten common bread on holidays and important days.

Hence, Valtellina’s panun, Genoa’s pandolce, Siena’s panforte, Lazio’s pangiallo—were all simple sweetened breads. The list is long throughout Italy. But only Milan’s Christmas sweet bread went beyond the city’s borders to become an institution.

Already in the second half of the 19th century, many Milanese pastry chefs were churning out panettone in near industrial quantities. Cova, Tre Marie, Biffi and Marchesi are historic pastry shops that had just opened at the time.

For Christmas, one of the most appreciated gifts was a panettone from those prestigious brands. Nothing said you cared like an expensive, finely packaged sweet made with high-quality ingredients.

It was the dessert of the upper middle class and the highest cultural classes. Giuseppe Verdi and Gioacchino Rossini both thanked publisher Ricordi in a letter for having received a panettone as a gift. Composers Giacomo Puccini and Arturo Toscanini argued because of a panettone.

The story goes that during a period of intense disagreement, Puccini discovered, to his chagrin, that Toscanini’s name had not been dropped from his Christmas gift list of panettone. He then telegraphed Toscanini—“Panettone sent by mistake, Puccini.” He received the telegraphed reply—“Panettone eaten by mistake, Toscanini.”

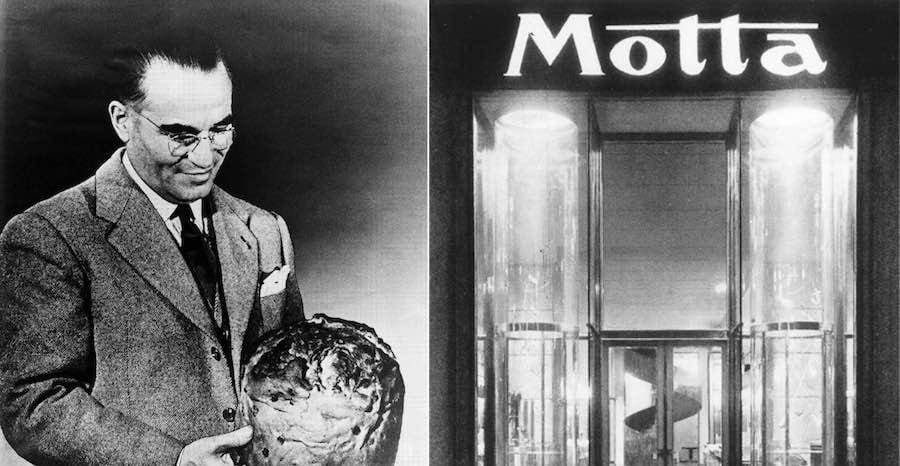

Until 1919, panettone was a low affair.6 1919 is the date when enterprising Milanese entrepreneur Angelo Motta decided to add more butter, eggs, sugar and candied fruit, and increase the leavening.

To reach the volume and shape we know today, with the air pockets and the intense yellow coloring, he needed a lot of soft dough on top of a support. Motta’s genius was the paper mold and crown.

“He increased the doses of butter, eggs, sugar and candied fruit considerably, modified and increased the leavening and cooking time and, because the pasta, so treated, becomes softer, to support it he used the ingenious and simple solution of wrapping in a crown of paper—this is how Motta’s panettone was born.”

Orio Vergani, Italian journalist, photographer and writer

As these things go, Motta’s inspiration for the additional ingredients was not flour of his bag (‘farina del suo sacco,’ Italian saying.)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On Value in Culture with Valeria Maltoni to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.