Published n. 6: Neglect for useful things

Demand wins, which is problematic because supply matters.

Below is my latest on the recent stories and articles where culture and value collide. The loose theme of this week’s briefing is about walking in someone else’s shoes. This video of the making of the LoMer shoes is incredible.

It’s one of the two Italian brands I favor—the other one is Scarpana. Because they’re well made, comfortable, last a long time, and are beautiful. We underestimate the value of beauty in supply.

On Value in Culture is a reader-supported guide to the role of narrative, language, and art in how we organize, perceive, and communicate about reality. Support my work with a paid subscription.

1/7 Since the last round-up, On Value in Culture published:

(🔒) Change in habits, behaviors, attitudes—From bias, to change, to heartfelt priorities: how do we learn what sticks long-term?

Agency—The part where you go off-script, that’s agency.

Why the Curious will Win by Having a Universal Gaze—How I learned to stop worrying about terrible behaviors.

(🔒) Why it’s become harder to keep promises—A framework to understand what's going on.

A reminder for supporters that they can access full articles and commentary at The Vault (🔒). Thank you for supporting the work on value.

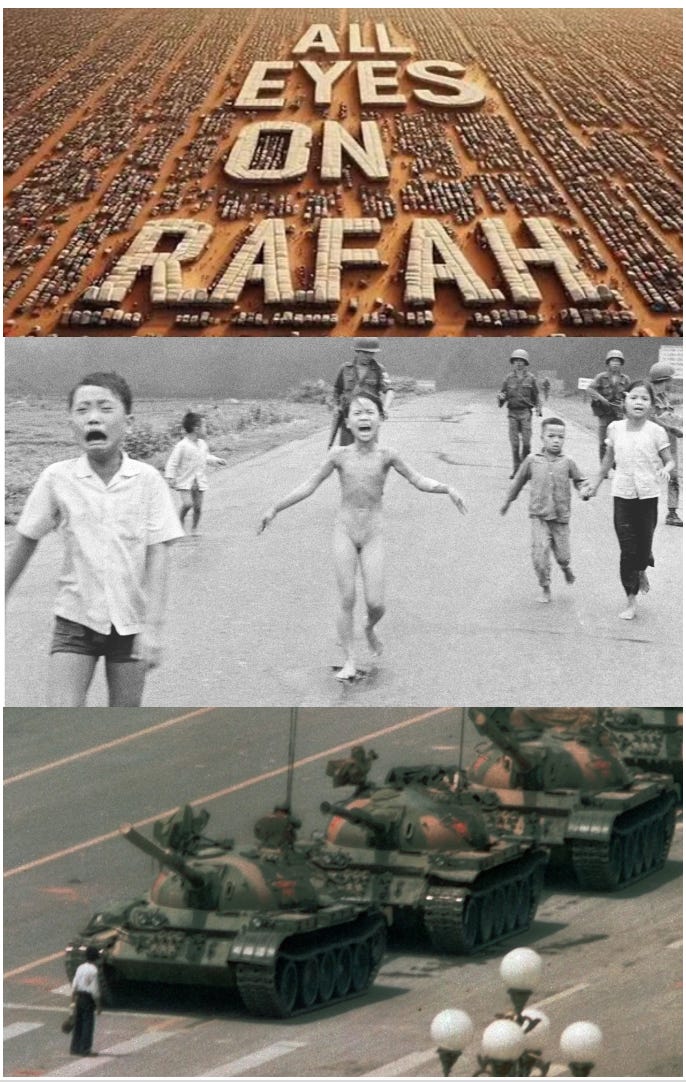

2/7 Paolo Ibichino is an independent copywriter and creative director. This week he shared an image composite many of you may recognize.

With it, he noted how:

There was a time when photographs served to undermine power, a dominant idea, or to build a collective imagination that based its reasons on an assumption of truth that the shot made somehow unbearable.

The assumption of truth in the new images built by platforms and artificial intelligence has abdicated its function. Because it’s no longer the time and there’s no longer time to ‘read’ the photographs. The scroll wins. Of the images on our feeds we are left with surface pixels, they make us feel part of a whole.

To avoid being left out of the great global conversation, all you need is your thumb, because digital activism has convinced us that we don’t have the tools to stop a war.

When activism was done through politics, the image disturbed the imagination and millions of disturbed individuals used the streets, the vote, the meetings, the clashes, to shake the power, or a dominant idea.

There was an assumption of truth, which digital platforms and artificial intelligence have made increasingly vulnerable, and our collective consciences no longer have to do with politics, with what we believe in, but only with computing power of algorithms, working to make us feel less alone. And more and more helpless.

His statement mixes many threads.

But the main thought seems to be that there was power in a photograph—as witness account and testimonial, it moved us to action—while the ease of AI-generated images keeps us scrolling.

Perhaps the image/slogan comes after the action in this case. To bring visibility to the images we’re not seeing. And I would venture to say that photography—professional and amateur—stands in even starker contrast to the cloned and airbrushed.

However, the better question is of the narrative we associate with an image and the situation it represents.

Digital platforms and artificial intelligence have moved the conversation from what is true when examined by reason (aletheia) to what is true because I trust (veritas.)

Is our trust well-placed?

3/7 AI changes the narrative, and also the scope of professions—from shifts in degree to shifts in kind. Bruce Schneier has a few plausible ideas that may well shift democracy.

He starts with what AI is good for:

First, it is really good as a summarizer. Second, AI is good at explaining things, teaching with infinite patience. Third, and related, AI can persuade. Propaganda is an offshoot of this. Fourth, AI is fundamentally a prediction technology. Predictions about whether turning left or right will get you to your destination faster. Predictions about whether a tumor is cancerous might improve medical diagnoses. Predictions about which word is likely to come next can help compose an email. Fifth, AI can assess. Assessing requires outside context and criteria. AI is less good at assessing, but it’s getting better. Sixth, AI can decide. A decision is a prediction plus an assessment. We are already using AI to make all sorts of decisions.

To translate the above competences to actual useful AI systems the details matter. How far and how soon are useful questions here. For our purposes, the value of his talk is in the second-order social effects.

Will the change distribute or consolidate power? Will it make people more or less personally involved in democracy? What needs to happen before people will trust AI in this context? What could go wrong if a bad actor subverted the AI in this context? And what can we do, as security technologists, to help?

A definition of democracy—“a system for distributing decisions evenly across a population. It’s a way of converting individual preferences into group decisions. And that includes bureaucratic decisions.”

Schneier brings up some interesting points for politics, the law, administrative stuff, and citizens. Can we provide confidentiality, integrity and availability where it’s needed? What would be in the way?

Incentives, risks and types of risk, environment, power, and the big one—trust—all matter. However, before we get to that, the current AI systems are ‘based on bias, theft, and noise,’ which are never a viable set of foundations for competence.

4/7 I’m not in love with the word ‘ordinary’ because in the current narrative everything must be so ‘exceptional.’ But if we hold to the meaning of the word, it would be ‘normal.’

It helps to explain further.

In the context of this article about business survival, it means not special, without expert knowledge. Ian Cassell relates a story of how Arthur B. Farquhar learned the most important lesson from Andrew Carnegie.

“No man will make a great leader who wants to do it all himself, or to get all the credit for doing it.”

Andrew Carnegie

It’s the human capital that can build nimble, sustainable organizations hard to replicate.

An exceptional business is one that can endure over a long period of time.

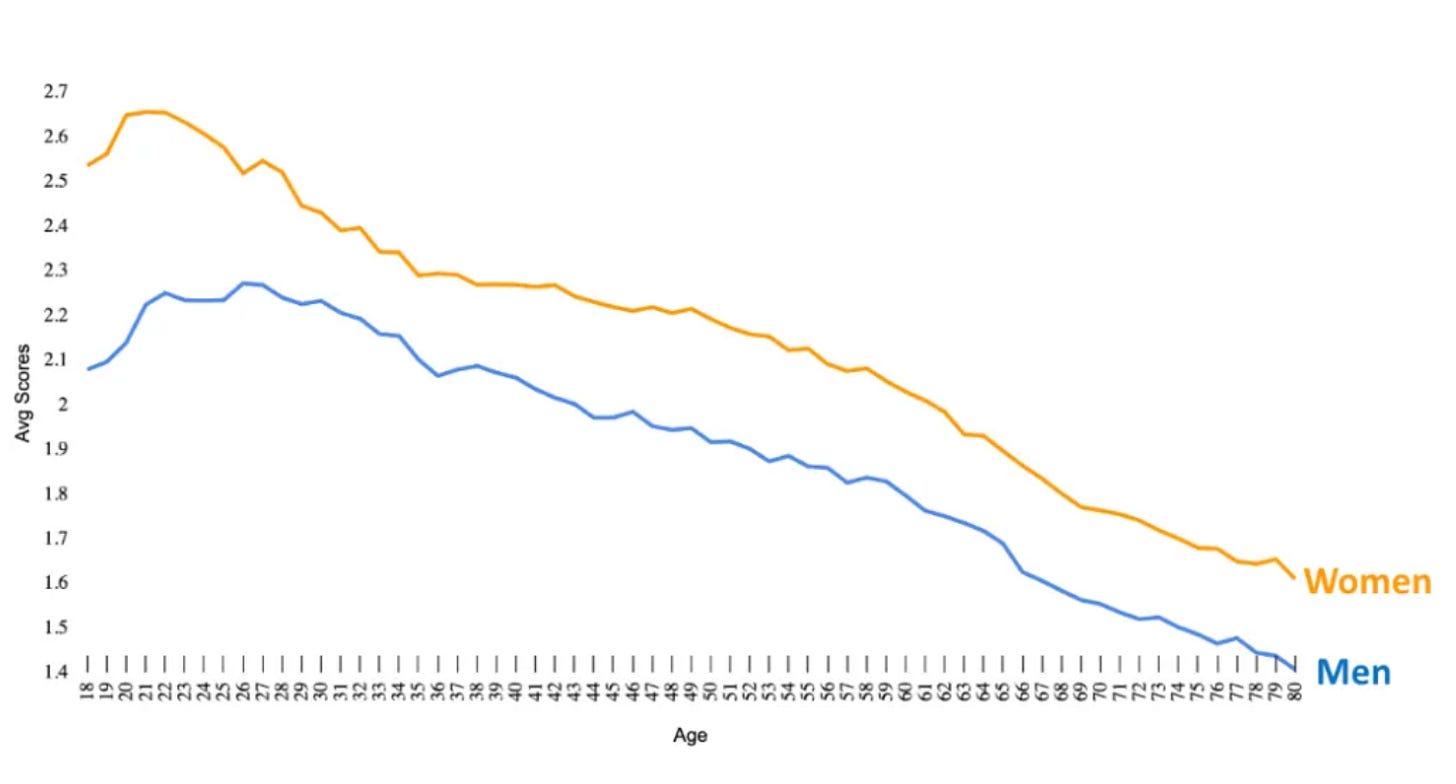

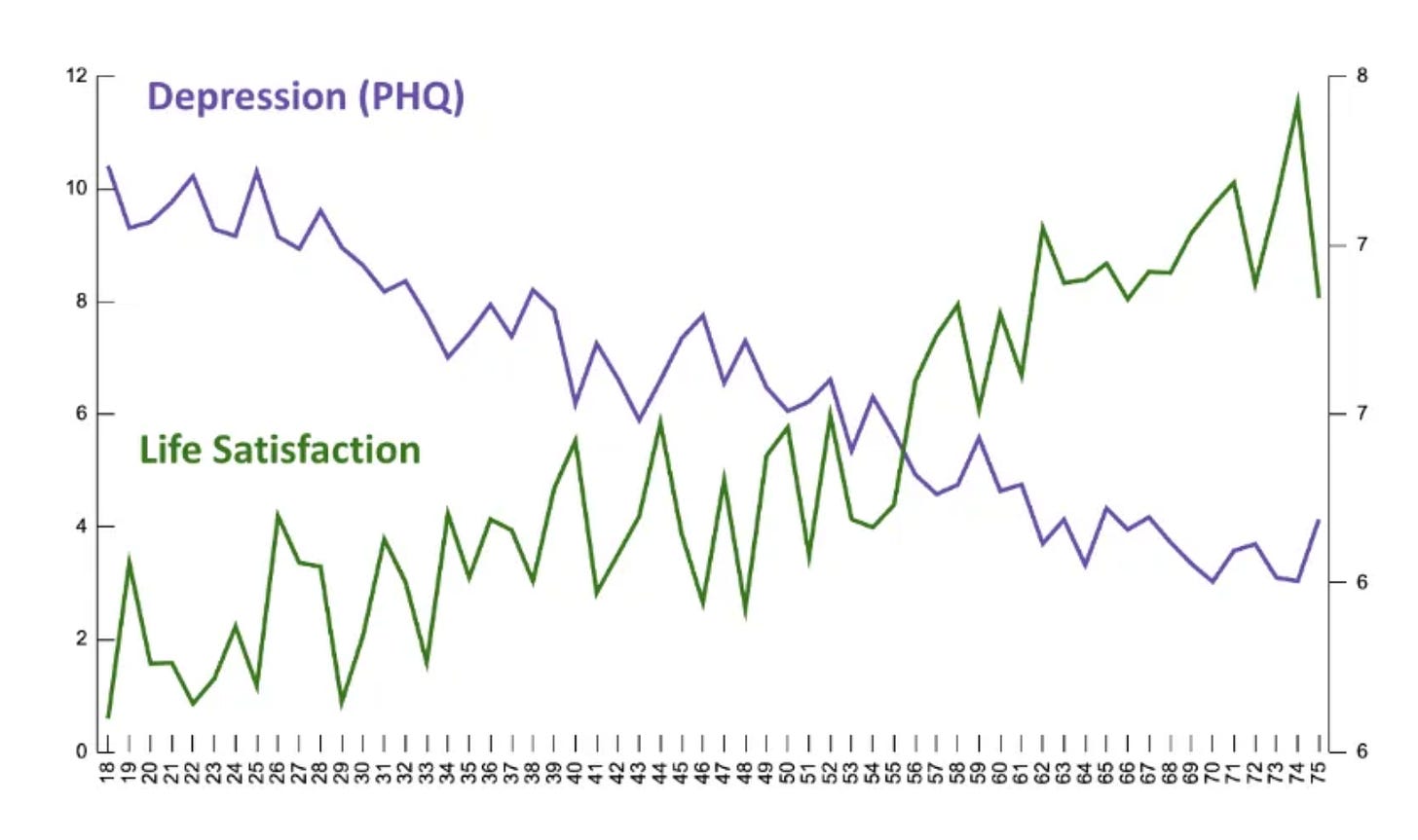

5/7 Jon Haidt notes that happiness is no longer U-shaped by age—young people are now the least happy.

Now, young adults (on average) are the least happy people. Unhappiness now declines with age, and happiness now rises with age—and this change seems to have started around 2017. The prime-age are happier than the young. The evidence for this transformation first became apparent in the United States and the United Kingdom, but it is now true in 82 countries worldwide.

The picture is dire in America (above) and is reflected in other parts of the world.

The decline in well-being involves another 48 countries. There’s a lot of data in the article, but little meaning. ‘Because technology’ cannot be the answer to all that ails younger generations.

There’s much more going on. As I told Peter, I think the data supports ‘value in use’— wisdom in old age. Having grown up in a generation where meaning and purpose were still central to life (and work), older people tend to have higher life satisfaction than younger.

The young are facing a world where relevance stopped being a good proxy for usefulness.

We have a problem of supply, says Peter. In as much as corporations have forgotten to prioritize the production of usefulness so too have individuals (and more so the young.)

The pursuit of intrinsic usefulness I associate with my own youth (a limited kind of self-sufficiency) has been replaced with extrinsic usefulness. First, replacing useful skills with the skill of working during the day. And at night replacing useful skills with working for social media companies to create their content.

Rather than spending energy creating something that is directly useful we have become conditioned to “create something useful for others in the hope that what we receive will buy something useful in the future.”

And if my thesis is right and usefulness is a prerequisite for change, the result is that we become or feel powerless to change. Leading to deaths of despair and leaving the door open to those who take power by promising it.

‘Change’ in value terms is critical. Without useful things, the will to change does not equal having the power to change. Because things with the greatest value in use are in short supply.

And more urgently given the number of elections this year, it’s worth remembering that the wicked take power by promising it to those who think they have none.

6/7 Amanda Guinzburg has the one about women. The essay is alive, a lucid piece of writing and I invite you to read it in its entirety. Accountability sounds like this (I’m leaving the emphasis from the original.)

It matters to those of us who understand whatever bravado and quick wit Stormy Daniels deployed in that hotel room and that she has been deploying ever since didn’t truly protect her; it didn’t prevent her from having to wear a bulletproof vest to court. And it didn’t prevent her from feeling trapped, manipulated, ashamed, and alone in that Lake Tahoe bungalow in 2006. Every woman you’ve ever known has some version of this experience locked inside her psychic vault where we shut our eyes and conducted a Houdini-like escape. His smell, his taste, his weight. We disappear. Or float above, separate from ourselves. What many men will never comprehend is that being forced isn’t necessary to feel cornered, and consent doesn’t mean we won’t hate it.

And, yes. I know: this case was not actually about the sex. It was about a conspiracy to cover up the payment to the woman with whom he had the sex. It was about the campaign. Still, it matters. That they listened to her. That they believed her. And, for better or worse, the decision by cable news to air wall-to-wall coverage mattered, too. Because it meant an entire nation’s gaze was directed back where it originally belonged. Back to his words and his behavior. His shame.

I did a double-take when I read the line about “every woman you’ve ever known has some version of this experience…” because I was eight, going to school on a public bus, and didn’t appreciate the grubby hand of an old man.

Alone, trapped, and powerless—that’s how it feels.

And it takes extraordinary strength to speak up from that corner. Contrast that with the ease with which one can deny their actions and expect to get away with it (or worse, point the finger in your direction.)

The difference matters.

I did speak up, the whole bus heard it—the old man had to exit at the first available stop, in shame. But the incident staid with me.

7/7 The divergence of narrative and opinion is intense. We must figure out the tradeoffs. Steven Novella on the distinction between clickbait and misinformation. Where one is disappointing, the other is dangerous—or are they?

One mainstream article may be read by 54 million people, while a Facebook post flagged as misinformation may be read by only 0.3% as many people. Part of the reason this may be surprising is because we tend to intuitively underestimate the impact of very large numbers (we are just not wired to deal with such numbers).

Clickbait is most dangerous.

Because it can be both misleading (i.e. not represent accurately the gist of the story), and spread very broadly (because mainstream media gets more eyeballs.) Even headlines have to make money, and that’s too bad.

Here again is the demise of ‘value in use.’ A good headline used to be one that was correct on the story it introduced—i.e. Trump unanimously convicted on all 34 counts conveys what happened and is neutral on emotion.