Shifts in Media Culture

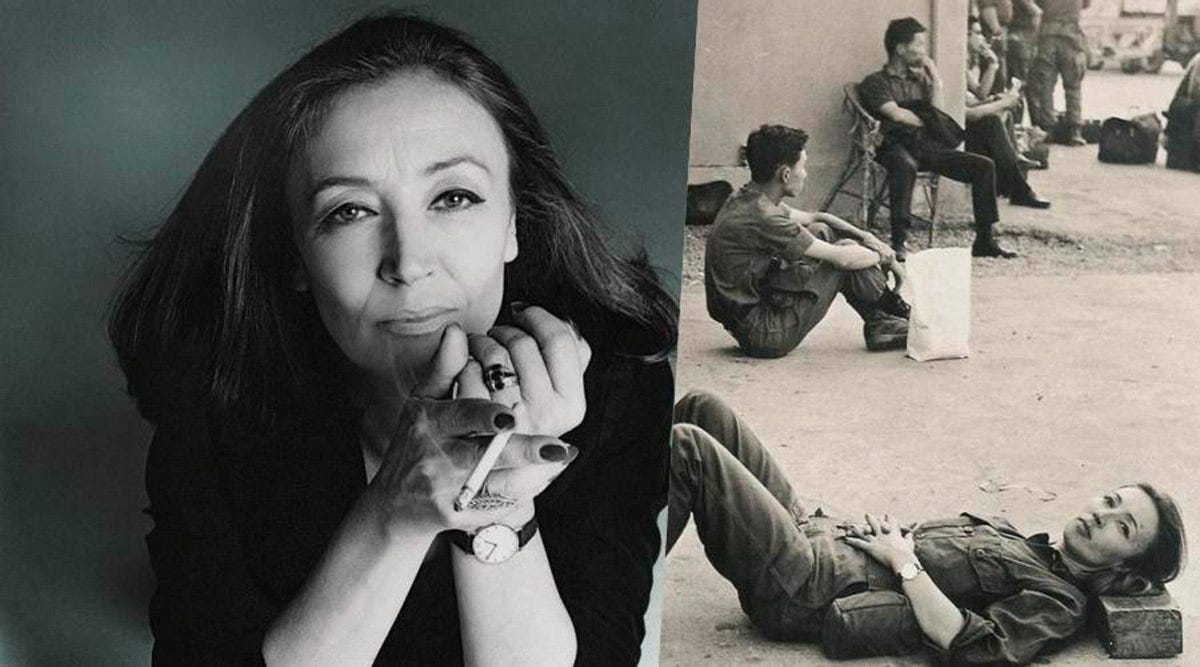

How Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci exposed some of the world's most powerful and intransigent political leaders, and made history with them.

Journalists have gone soft. They sit through non-answers and go on to the next question on their list as if an interview could have no consequences. These days, there’s no real confrontation anymore, just a regurgitation of slogans.

Oriana Fallaci didn’t break the ice, nor did she hold the media’s megaphone so that the powerful could spout all the boilerplate they wanted. She went straight to the core of the matter.

Always prepared, always focused on the most relevant issues of the day, the Italian journalist maintained a professional skepticism. She didn’t let anyone burble and take detours. She’d call them out and bring them back to the question.

As a result, she was both respected and feared—a unique combination likely also due to her personality, but in grand part due to the diligent background knowledge behind every question. She knew history and understood human complexity.

Where that degree of commitment and passion exists in journalism today it’s with independent voices.

The shift in media culture tends towards soft-powder questions, bi-sidesisms, mere transcriptions of talking points in many publications,1 where it’s not blatant polarization and propaganda altogether.

We’re now left to our own resourcefulness to make sense of what happens ‘on the ground.’ Because things begin to exist when we notice them, Fallaci knew what was at stake—her journalism active conversation with power and influence.

Reminder: You can support my work and get extra insights—in-depth information, ideas, and interviews on the value of culture.

Join the premium list to access new series, topic break-downs, and The Vault.

The Italian journalist approached her interviewees as their intellectual peer and social equal, without inhibitions. Though Fallaci wrote three novels and five works of nonfiction, she’s best known as a political interviewer.

A short example of the shift in media culture can help us for context. Here’s Dan Rather in a February 2003 interview with Saddam Hussein.2

Dan Rather: “Mr. President, I hope you will take this question in the spirit in which it’s asked. First of all, I regret that I do not speak Arabic. Do you speak any... any English at all?”

Saddam Hussein (through translator): “Have some coffee.”

Rather: “I have coffee.”

Hussein (through translator): “Americans like coffee.”

Rather: “That’s true. And this American likes coffee.”

You can likely already see the tentative breaking of the ice, the small talk. At no point during the interview, Rather asked about Hussein’s spotty record on human rights. In fact, CBS held its megaphone for the leader’s talking points.

Rather: “Are you afraid of being killed or captured?”

Hussein: “Whatever Allah decides. We are believers. We believe in what he decides. There is no value for any life without imam, without faith.... The believer still believes that what God decides is acceptable. Nothing is going to change the will of God.”

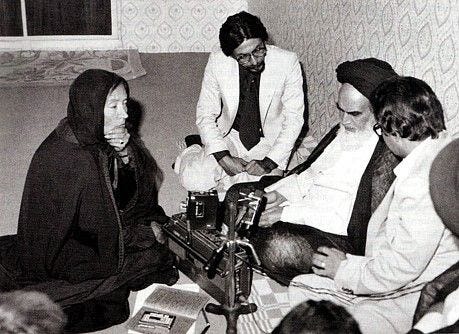

And here’s how Fallaci approached a world leader.

Oriana Fallaci: “Why do you compel women to hide themselves, all bundled up, when they had proved their equal stature by helping to bring about the Islamic revolution?”

Khomeini: “The women who contributed to the revolution were, and are, women with the Islamic dress; not women (like Fallaci) who go around all uncovered, dragging behind them a tail of men.”

It must have sounded like a non-answer to the journalist, because she asked another question. One that sounded insolent to Khomeini.

Fallaci: “How do you swim in a chador?”

Khomeini: “Our customs are none of your business. If you do not like Islamic dress you are not obliged to wear it. Because Islamic dress is for good and proper young women.”

Fallaci: “That’s very kind of you, Imam. And since you said so, I’m going to take off this stupid, medieval rag right now.”

No half apologies, no irrelevant talk about coffee. Fallaci then yanked off her ‘chador.’ The interview thus ended abruptly as the Libyan leader left the room.

“At that point, it was he who acted offended. He got up like a cat, as agile as a cat, an agility I would never expect in a man as old as he was, and he left me. In fact, I had to wait for twenty-four hours (or forty-eight?) to see him again and conclude the interview,” noted Fallaci.

When Khomeini let her return, his son Ahmed told Fallaci that his father was still very angry. She’d better not even mention the word ‘chador.’ Fallaci turned the tape recorder back on and immediately revisited the subject.

“First he looked at me in astonishment. Total astonishment. Then his lips moved in a shadow of a smile. Then the shadow of a smile became a real smile. And finally it became a laugh. He laughed, yes. And, when the interview was over, Ahmed whispered to me, ‘Believe me, I never saw my father laugh. I think you are the only person in this world who made him laugh.’ ”

Because of the deep background legwork to prepare for each interview, Fallaci guessed the leader’s most vulnerable bits to base her questions. Added to the sheer depth of her knowledge, her intelligence caught her subjects off guard.

She also brought the other side into the interview via clippings and recordings. She summarized and stimulated rash responses. Her perspicacity allowed her to grasp the heart of the matter, to read the signs of unease in her subject.

Fallaci varied her techniques. She went from the general to the particular through the use of a hypothetical, or a specific instance. Other times she’d take her subject on a safari of many questions before she cornered them intellectually.

Her originality was the emotional entanglement with the other person. Fallaci had a high degree of involvement with her subject. In an interview with Mike Wallace on 60 Minutes, she said:

“I hate objectivity, you know, I have told it many times, I do not believe in objectivity, I believe in what I see, what I hear and what I feel which is a kind of blasphemy… especially for the American press.”

Fallaci threw her entire being in the conversation. That’s how she became skilled at inductive reasoning. She listened to her subject’s statements and drew conclusions. For example…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On Value in Culture with Valeria Maltoni to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.