Love: the Most Fundamental Market Principle

How duty, learning, and friendship contributed to the foundation of trust.

You’ll forgive the Franciscan for owning only one tunic. Clothing was a sign of wealth in Italy’s flourishing economy of the 13th Century. Even expensive vellum manuscripts were frowned upon. Books were alright, but purely as tools for learning. Though it was alright to give gifts to the monastery.

There were rules of spiritual utility. But it was the monks who first attempted to put a price on things. The law of diminishing marginal utility was the work of French Franciscan Peter John Olivi. It says that the more available something is, the less value. Durability also affected price: goods you could store were worth more.

At around 1279, longevity mattered.

Reminder: You can support my work and get extra insights—in-depth information, ideas, and interviews on the value of culture.

Join the premium list to access new series, topic break-downs, and The Vault.

The Franciscans were a self-regulating order that dealt with the constant change of what we call the middle ages. Their system of quantity, utility (rather than morality), accessibility, and durability was a challenge to the Church. And the Church was the most powerful institution.

Olivi was the chief visionary writer of economic theory during that period. His 1293 Treatise on Contracts “draws on law, philosophy, and theology in order to present a global view of economics that manages to combine the free will of individual agents and the normative capacities of political communities.”

Leave pricing to the ‘expert’ merchants, he wrote. Only they understand the relationship between product and services. Merchants knew the demands of the common good—i.e. the value of labor in a specific market.

Have you ever wondered, “how did we get to where we are?” Capitalism was invented in catholic monasteries. 900 years before Karl Marx, Olivi and the Franciscans talked about ‘capital’. During that heady time, money lacked intrinsic value, “because money itself is not lucrative.” Value came “through the activities of merchants in their business dealings.”

In the light of that argument, resellers were immoral—they didn’t add value. Value was in the labor, skill, and risk-taking that went into a product. Three ingredients that contributed the the enormous wealth concentrated in Northern Italy, even to this day (despite the current challenges).

English Franciscan friar William of Ockham developed further the modern concept of the individual and subjective choice in the marketplace. In the 1320s, he echoed in the constitutional, republican city-states of Northern Italy, where citizens enjoyed relatively high levels of personal economic liberty.

Giacomo Tedeschini asked again the question of “what is value?” in the later middle ages. The Professor of Medieval history at the University of Trieste saw on one end of the spectrum the spiritual, which didn’t prevent a sophisticated use of the balance sheet. On the other were possessions and market functions.

Another Italian, Niccolo’ Machiavelli, stated that the marketplace cannot work if it becomes destabilized by oligarchs or a dictator who uses the city and the market for his ends and undermines the balance of politics, ethics, and peace. Unequal wealth can lead to factions, strife, and war.

It’s up to the state to keep peace and oversee a fair function in the market. Machiavelli’s ideas were the precursors to how to build a state. And that’s precisely where my conversation with Jacob Soll began—on the power of institutions. State building in the 16th and 17th centuries is a chapter in Free Market, as is the role of the Church in laying the foundation for the modern state.

We’re generally pretty good at knowing the big things that happened in the past, but we tend to lose much of the nuance of how ideas formed and developed historically. But what are histories if not hypotheses and theories about how change occurs (cit. Neil Postman). They themselves are a product of culture.

A notion that has become central dogma in economics—the ‘Free Market’ ideology—is due for serious reappraisal.

Religion, politics, geography, and economy of a people lead them to recreate their past along certain lines. Culture and commerce are weaved together.

Soll is Professor of philosophy, history—and accounting—at the University of Southern California. He’s lived in France and spent considerable time in Florence. For that reason, he’s developed a taste for slow food and cultural immersion. Christianity grounded commerce in human desire, he says. The republican city-states of Northern Italy completed the work.

To understand where the idea of profit-seeking being essential to creating a virtuous commercial republic (and a healthy market) came from, take a stroll down history lane with me and Prof. Soll. 1287-1355 Siena was the leader in European banking. A city-state along with Florence, Genoa, and Venice. For hardworking merchants earning wealth through industry, trade, and finance was virtuous.

Tracing the historical roots of “money” and “capital” can help us see the cultural significance of these concepts in our current narrative. The commons’ role in building infrastructure in the Netherlands had its roots in the Dutch traditional of communal investment. Citizen-investors working together. By the mid-17th century, the Dutch economy was the most sophisticated in the world.

The mix of technical expertise and cultural influence of Italy was not lost on Jean-Baptiste Colbert. French Prime Minister Colbert, a trained accountant, created a new brand for France—a nation of industry, innovation, and luxury. If he borrowed on crafts and culture from Italy, he also took from Spain—the imperial might—Holland—the commercial prowess—and England—development economics.

We borrow liberally, too.

Perhaps retracing our steps in the origins of industrial reform and the birth of capitalism can help us find a way out of the current predicament.

We knew early on that good management and investment in infrastructure were key. Somewhere along the way we lost the idea that infrastructure includes education. The 19th Century novel captures the complexities of society as only works of literature could. Very few read those novels anymore.

Reading hard books, Roman and Greek philosophy, writings by the fathers of the Church, serious study of the humanities, and patronage of the arts were foundational to the Renaissance.

Firenze knew the value of the creator—she represented God’s power. Cosimo de’ Medici had a particular fascination with Donatello—a scholar closer to God. Which is why his Marzocco statue graces Piazza della Signoria with the symbol of the city.

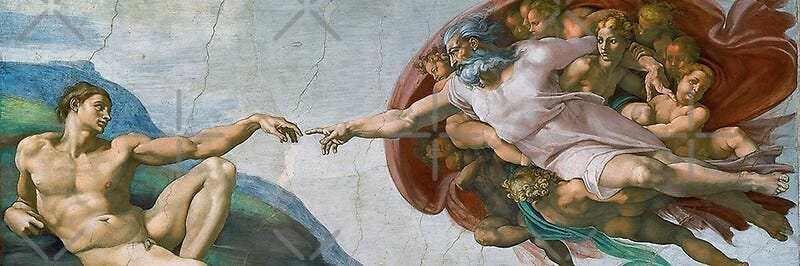

Think of the spark of creation Michelangelo painted in the Sistine Chapel. Many workshops of painters and artisans had to make slow, technical, cultural and artistic advances before the Sistine Chapel was possible. Michelangelo draws upon that rich history and those learnings.

Capitalism is about relationships, which are more unique than ideas. Knowledge is part of that. But a slow, deep knowledge that involves many domains. A slow process of learning increases your capacity to deal with challenges. Good teachers, history and literature are part of life. According to Soll, they also have a deep connection with finance.

How have we turned to the worshiping of finance

at the expense of the value of everything else?

On December 10, 2019, Scott Timber, an exemplary journalist who covered arts and culture with deep knowledge and acute insight, took his own life. “Scott had lost his job at the Los Angeles Times shortly before he turned 40. In a final ironic twist, he had just received a glowing performance review a few days before the round of layoffs that left him unemployed.”

He never recovered his bearings.

Boom Times for the End of the World, his (posthumous) collection of twenty-six reflections, is a valuable window onto the many cultural shifts that have upended the creative traditions and expectations of America.

Los Angeles, where Timber (and Soll) lived, is a greater artistic center than San Francisco—where most technology hails from. Italian sound designer and composer Diego Stocco calls LA home as well.

But go to many centers of higher education and you’ll find that students don’t know history, the historical evolution of art, culture—the very tools that build the humanities, and perhaps can help us make more humane decisions.

With the shift from the Roman Republic to the Empire there was an injection of morals in thinking and dealings. A healthy market meant that ethical people could trade in confidence. Decorum and self-control were seen as virtues.

Duty, learning, and friendship contributed to the foundation of trust. Which is how love was the most fundamental market principle.

Trust holds the contextual wealth that goes along with human development and the richness in possibility.

This kind of trust is very different from what technology is building. Consider how:

Rather than improving the organic search algorithm of Google, Sundar Pichai dilutes the value of honest writing to maximize short term profits—Bard is part of that aim.

Adding insult to injury by way of product additions nobody requested of Microsoft, Satya Nadella adds AI nobody can trust to Bing—making Skype less safe for all.

Instead of increasing the trustworthiness of Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg bet the entire company on something fake—metaverse is a failing proposition.

Last because least on a platform that had so much promise in the early days, Elon Musk makes a mockery of the Twitter verification system—and shows his greedy hand by putting it up for sale.

These are some of the biggest companies in the world. What do these CEOs choose from the comfort of their modern thrones? They have tremendous influence on what people see, find, and do online—inside and outside the corporate walls.

Clearly, they overlook the fact that trust has a lot more value than what they put out there. Look at the data [source]:

91% of business executives say their ability to build and maintain trust improves the bottom line—but leaders overestimate how much customers (by 57 percentage points) and employee (by 14 percentage points) trust them.

46% of employees whose company had a trust-damaging event in the last year say they expected it—customer service issues, lack of transparency, bias and mistreatment all lead to mistrust.

79% of consumers say protecting their data is very important to building trust—but only a fraction of companies disclose data privacy policies and are transparent about hiring practices and operational risks.

Trust develops in response to trustworthiness.

Looking back at history to the periods that built wealth for societies, trust was front and center, not an afterthought. The kind of trust we’re talking about converges with love.

Traces.Dreams:

At minute 1:02:40 I talk about the ideas and relationships behind Traces & Dreams, which produce the podcast. Making knowledge accessible and available more broadly, embracing different perspectives were part of the impulse behind the founding series—“idioms of normality” with host Dr Paul Mason and “inequalities” with host Dr. Alice Krozer. Find all the videos here.

Join the Olympus:

“The mind does not open unless the heart opens first,” said Plato. The ancient Greeks had the Olympus and its gods as a method of inquiry into human feelings.

Mount Olympus was the highest and most worshiped mountain of Greece. The Greeks put parts of their nature in the Olympus so they could talk to them and understand the self. The gods were living their lives with a similar rhythm to mortals, obeying rules, abiding customs and gathering from time to time in Zeus' palace for small conferences.

With the myths, knowledge, and stories, we’ve lost that connection. Being in the world (rather than in its representation/simulation) means we know how to deal with feelings. But if your mind is empty of tools to deal with suffering and pain, you’re lost.

Coming up:

The next conversation I will be releasing on Traces & Dreams will be on “value in emotion.” It will be an exploration of key themes in Between us: How Cultures Create Emotions with Prof. Batja Mesquita. Emotions are not innate, but happen between people and signal a taking of a stance in relationships, both one-on-one and within larger social networks. That’s the main thesis and argument in the book. But there’s a lot more to it—and that more is culture.

Nice to know I'm not the only one looking back at humanity through a relatively anthropological lens these days. 😉 Our endlessly optimized, data-driven lives are increasingly homogenous (average) and automated (thoughtless), opening us up to boredom and a creeping sense of nihilism.

I find myself thinking back to simpler times, hundreds, if not thousands of years ago. Sure, life was literally harder in every way, but what about our needs? How have those primitive requirements for giving up the nomadic life to settle down changed?

The comments above around value, commerce, and parasitic middlemen really hit home. It would be hard for me to find a friend these days who *wouldn't* prefer dealing with smaller, local brands and businesses, where they can build trusted relationships and feel good about their spending habits.

How do we tap that in the face of such extreme, ingrained convenience at all costs?