That's bananas!

The human cost for the fruit that became a consumer staple and cultural symbol.

I’m allergic to bananas. And maybe there’s a reason for that. Because once you look into the history of the success of this exotic fruit, you’ll find too much intrigue. For there’s a painful story behind the production, marketing, and distribution of bananas.

In fact, the history of the first modern multinational is a story of power, oppression and greed.

Behind the bananas people consume every day, there’s the blood of many workers, the collapse of democratic governments and a widespread sense of injustice that’s still sadly alive. That multinational is United Fruit Company (now Chiquita.)

On Value in Culture is a reader-supported guide on the role narrative, language, and art play in how we organize, perceive, and communicate about reality. If you want to support my work, the best way is with a paid subscription.

When Gabriel García Márquez published One Hundred Years of Solitude in 1967, just under forty years had passed since the day the Colombian army shot and killed striking United Fruit Company banana farmers in Ciénaga.

“Several hours must have passed since the massacre, because the corpses had the same temperature as chalk in autumn, and the same consistency as petrified foam, and those who had placed them in the carriage had had time to stow them in the order and sense with to which the bunches of bananas are transported.”

Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

‘The Banana Massacre’ of 1928—as they called it later—remained quite nebulous, such was the zeal with which the Colombian government covered up the event. Even today, almost a century later, the extent of the massacre remains elusive, the victims an incalculable number between 47 and 2,000, and forgotten.

Many events in the history of the United Fruit Company, now Chiquita Brands International, have similar characteristics. Despite having been told over and over again, that of the most powerful multinational of the twentieth century is a story that has never really settled into public debate.

Perhaps because bringing that memory to light would mean dealing not with one, but multiple massacres. And also with the exploitation of thousands of workers in the torrid plantations of Central America, with intrigues and political machinations that have ousted the governments of sovereign nations, even with genocide.

All in the name of bananas, but above all of power.

Another reason for this oblivion is perhaps that the United Fruit Company managed to create a model of a multinational that still exists today. And which, with the approval of the United States, continues to act in ways similar to those of a century ago.

We would have to admit that our memory is labile or very selective today as it was then. But the story of Chiquita (and its ancestor United Fruit Company) needs telling, because it’s still so relevant.

Origin story

It all started when American entrepreneur Henry Meiggs began the construction—in 1871—of the railway between San José, the capital of Costa Rica, and the port of Limón.

The fruit came only years later when, upon Meiggs' death, his nephew Minor Keith decided to plant banana trees along the track to feed the workers working on the railway at low cost.

Because he was dissatisfied with the local workforce, Keith had hired also two thousand Piedmontese workers. Exhausted by the poor working conditions, the Piedmontese ended up organizing what likely was the first strike in the history of Costa Rica, before running away.

To round things off, while the railway was still under construction, Keith began to import bananas, then still completely unknown, into the United States. He achieved some success quickly.

However, when the railway was finally completed in 1890, it proved to be an almost useless work for passenger transport, because the actual number of travelers between San José and Limón did not justify regular rail traffic.

But at that point Keith had the bananas—entire plantations of bananas—a train that could transport them to one of the largest ports in the region, and a nascent market in the United States ready to receive them.

Shortly afterwards, Keith married the daughter of the then President of Costa Rica, thus making the country effectively his. In 1899, the United Fruit Company was born.

‘Banana Republics’

The United Fruit Company grew rapidly in the first decades of the twentieth century’ It grabbed land in Central and South America—Costa Rica, Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, Cuba, and Panama.

The term Banana Republic—coined precisely in the late 1920s, early 1930s—describes the excessive power exercised by the United Fruit Company in Latin America: politically weak and corrupt states, prone to the economic interests of foreign multinationals.

By 1930, the company owned 1.5 million hectares of land across Latin America and controlled about 15,000 kilometers of railways, many of which the countries themselves built and paid for.

In his book Bananas, Peter Chapman1 describes the United Fruit Company as “the first capitalist model of the modern multinational.”

The signs were all there. At the beginning of the century, in Guatemala, the United Fruit Company already controlled the postal system, the radio and the telegraph company, as well as being the largest landowner in the country.

In San Josè, Costa Rica, it built the tram lines and installed the first electric street lighting system. Its hospitals, built to assist US executives visiting plantations (not the workers), became the largest private healthcare system in the world.

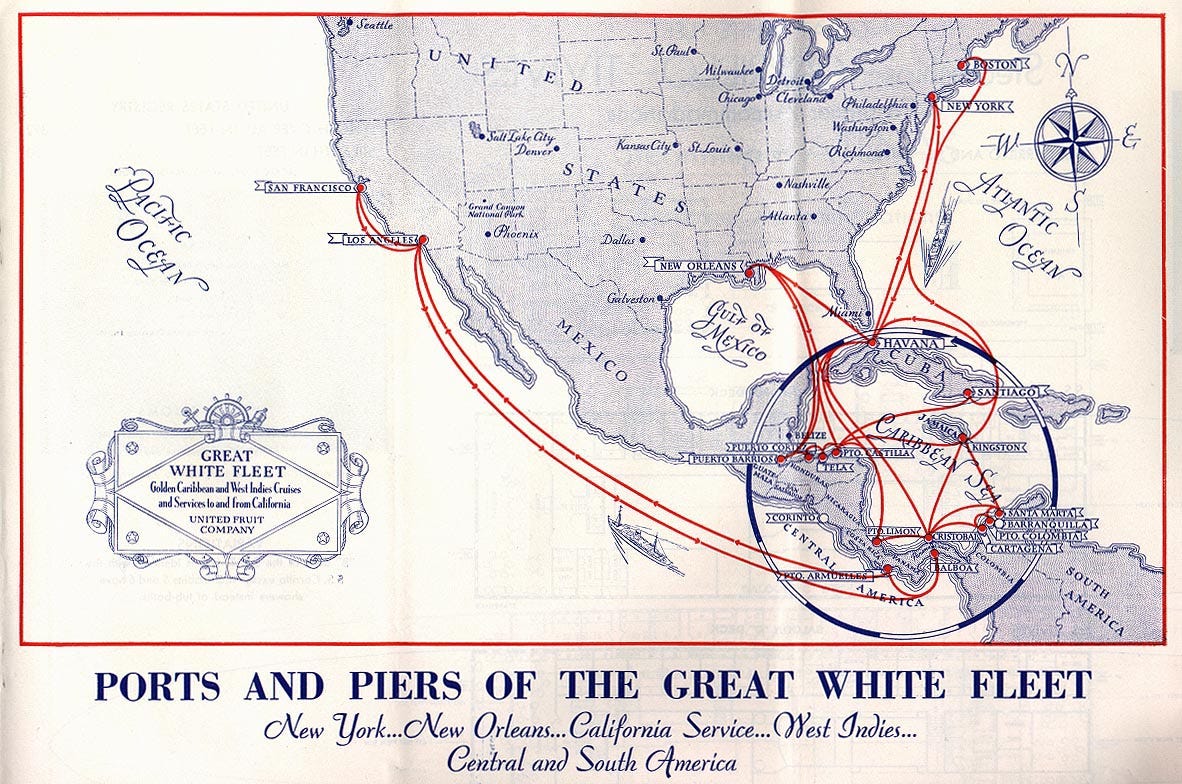

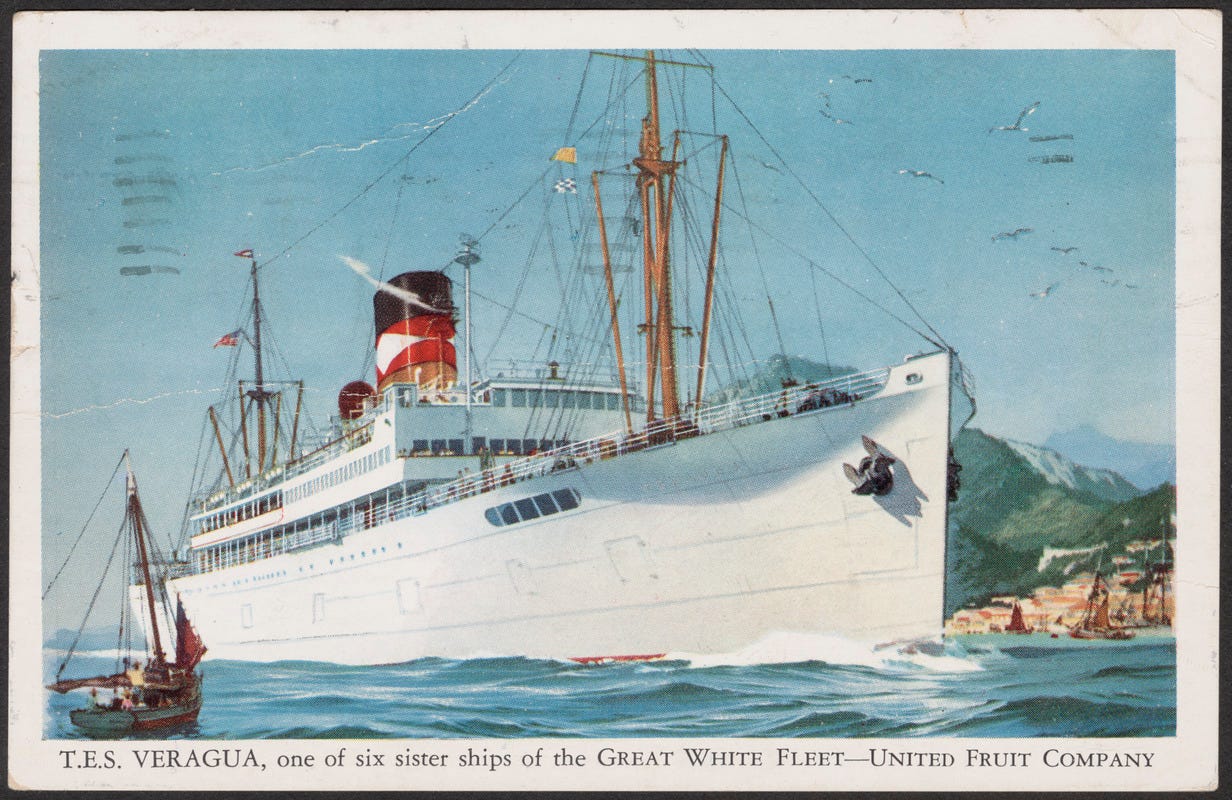

And then there was the ‘Great White Fleet,’ so called because its ships, painted white, reflected the sun, keeping the precious cargo of bananas destined for the United States fresh. Initially the ships’ use was commercial.

Around 1930, the ships also began to be used to organize glittering Caribbean cruises— transporting groups of tourists eager to visit the exotic countries from which that sweet fruit came.

When two of those same ships landed in Cuba a few years later, they did so for very different reasons. It was April 17, 1961, and the United States was preparing to invade the island in an attempt to overthrow the government of Fidel Castro.

That day, at the Bay of Pigs, while the world seemed close to a nuclear holocaust, there was also the United Fruit Company with its ships, willing to do anything to not let the Castro revolution undermine its hegemony.

It was not the first time, and it would not be the last, that the United Fruit Company resorted to extreme and violent measures to defend its interests.

A blind eye

The company had always enjoyed a certain immunity, if not formal, then surely de facto. Even as the United States began to regulate corporate operations, it soon became clear that the rules imposed on American soil would not apply to cross-border operations.

Already in 1928, when the banana farmers of the United Fruit Company were massacred by the Colombian army for daring to ask for more dignified work contracts, there had been no consequences.

In fact, the opposite happened. A few days after the massacre, the US embassy sent a telegram praising the speed with which the army had dealt with the ‘dangerous’ strikers.

When 100,000 workers organized to demand contractual reforms and better working conditions in Costa Rica in 1932, the army was sent to violently repress the strikes. At the end of the clashes, the United Fruit Company had only partially accepted the workers' demands, establishing a minimum wage and providing them with adequate housing and first aid kits.

Even if the strike later contributed to consolidating the trade union movement in Costa Rica, no one ever really paid for the violence that the workers had suffered.

Washington, however, did not just turn a blind eye. More often than not, the United Fruit Company could count on the complicity of the American government and the CIA for political and economic control of the region.

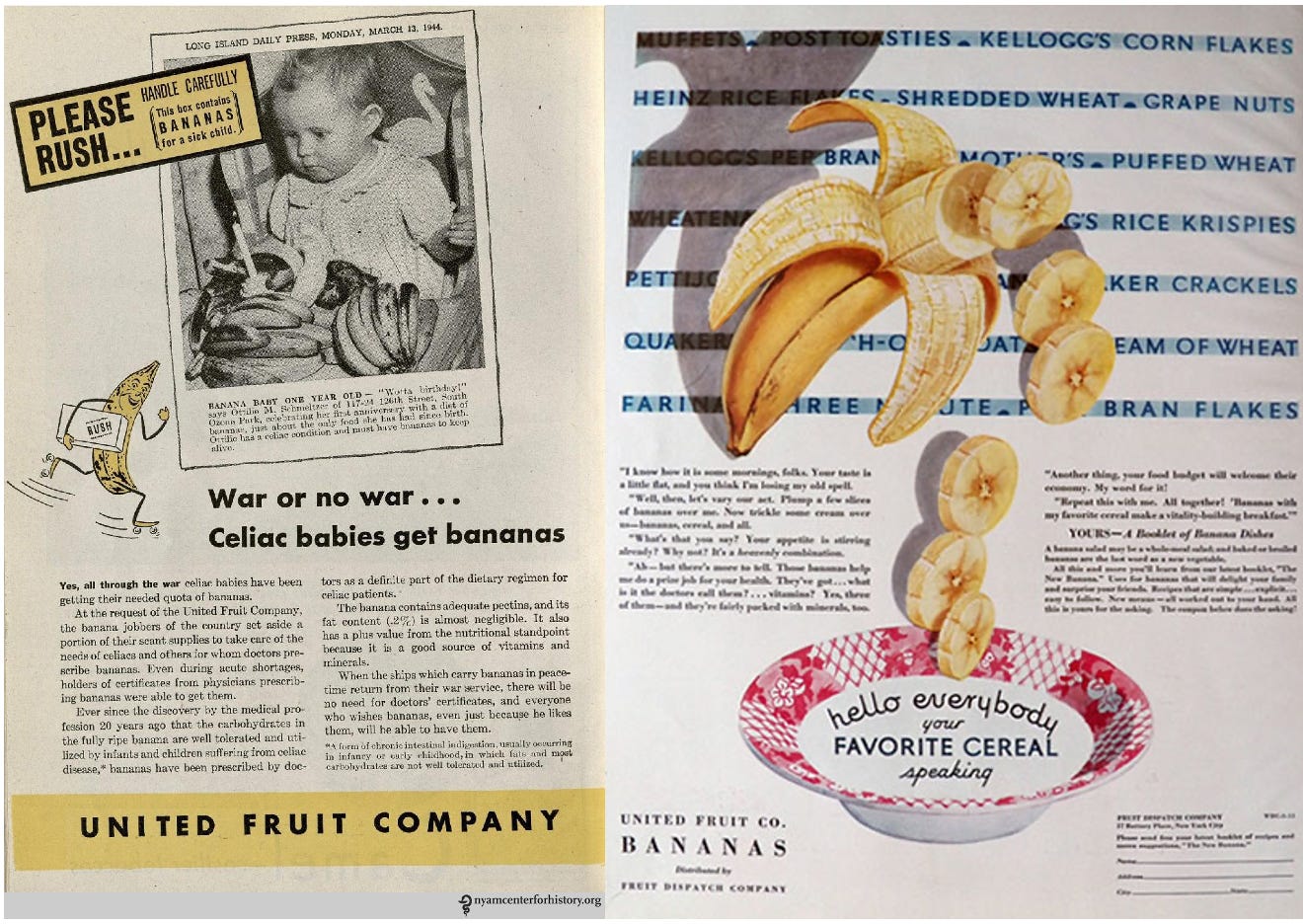

Meanwhile, in the United States, to the Caribbean notes of the Chiquita jingle, one of the most famous commercial gimmicks of the United Fruit Company, bananas were on display on the tables of all Americans.

By 1950, banana consumption in the United States had exceeded that of any other fruit. The brand name ‘Chiquita’ was trademarked in 1947, and a letter dated from that year2 depicts the early Chiquita brand logo.

By the 1950s, the United Fruit logo was reduced to a simple flag containing the letters UF as the Chiquita brand name started to take prominence in their advertisements3 (the company would undergo restructuring in the 1970s-1980s to eventually become Chiquita Brands International.)

A darker turn

Meanwhile, in Guatemala someone was trying to re-establish democratic balance for the first time since the United Fruit Company had gotten its hands on most of the country’s land.

After years of political uncertainty, a democratically elected president, Jacobo Arbenz, had come to power in Guatemala in 1952. He implemented a series of social reforms with the aim of strengthening unions and granting greater rights to workers.

In an attempt to gain economic independence from the United States, Arbenz initiated an agrarian reform to expropriate the uncultivated lands of the United Fruit Company, offering the company $1.2 million in exchange.

“It’ll cost you about $19,355,000,” said the United Fruit Company.

Since the beginning of its operations in Guatemala, the United Fruit Company had decided to cultivate only a relatively small part of the land it owned; the rest served mainly to prevent them from belonging to other potential competitors, who had never existed until then.

Fearful of losing their privileges in the country, however, the United Fruit Company, with the help of the CIA, tried to convince the US administration that Arbenz was a communist sympathizer, and therefore a threat to the country.

These were the years of McCarthyism and witch hunts—the accusations found fertile ground.

In June 1954, the US government authorized the CIA to finance a coup d’état aimed at overthrowing the Guatemalan government.4

Everything that followed—Arbenz’s escape to Mexico, the establishment of a dictatorship favorable to US economic control, the civil war, the extermination of the Mayan people who tried, against their will, to resist the dictatorship—happened because United Fruit Company did not want to risk losing its economic power.

200,000 people died, more than 80 percent of whom belonged to the indigenous Mayan people. The civil war lasted 36 years.

It was not the first coup d’état in which the United Fruit Company participated (Honduras had taken place years before) and it will not be the last (Cuba will take place shortly after.)

“[United Fruit] was far more powerful than the Guatemalan state.”

Stephen Kinzer, author and former New York Times correspondent

But the coup in Guatemala is one of the moments in the history of the United Fruit Company whose impact is so great that it is perhaps still difficult to fully understand today.

Meanwhile, the Sixties had begun not without problems.

A bitter fruit

In the decades that followed, the United Fruit Company will have to face major changes that will put its activities in crisis. Bruised and downsized, it finally managed to re-emerge from its ashes—though it no longer reached the heights of power it enjoyed in the first half of the twentieth century.

In Cuba, after the failure of the American coup, Castro had nationalized the holdings of the United Fruit Company, setting a dangerous precedent. Shortly thereafter, Costa Rica passed a law requiring the United Fruit Company to significantly increase wages.

A few years earlier, an epidemic had almost eliminated the commercial production of Gros Michel quality bananas, inflicting enormous economic damage on the multinational and forcing it to switch to other qualities, more resistant to the disease.

Thus was born the Cavendish quality which today constitutes 95 percent of world production.

The greatest damage, however, was inflicted by the United States itself, with the approval of a package of laws that gave the American government the power to control the activities of American companies abroad.

In this way, the United States could prosecute a company's illegal actions, even if those actions were legal in the country where the company operated.

In 1975, under the leadership of new CEO Eli Black, the United Fruit Company was accused of bribing the Honduran president by paying him $2.3 million to reduce taxes on banana exports.

This time the case really exploded.

On February 3 of that year, Eli Black died after jumping from the 44th floor of his office. The company found itself without a leader and with major legal problems to deal with.

Bribes had also been paid to other countries, both in Latin America and Europe, but this will come to light at a later date. It seemed that the end of the century would coincide with the decline of the United Fruit Company.

It wasn’t like that. Ten years after Black’s death, billionaire Carl Lindner took over the reins of the company and changed its name from United Fruit Company to Chiquita Brands International, like the very famous jingle that had helped make it immortal in the 1940s.

Chiquita was formed out of a defunct United Fruit in the 1980s. It’s no longer a US company. It’s now based in Switzerland and owned by Brazilian firms. But, it is still a huge banana producer.

In a century of history, which began along the tracks of a useless railway between San José and Limón, bananas, from exotic and unknown fruits that they were, have become the most consumed fruit in the world.

Chiquita continues to lead the global market, which it now shares with other multinationals including Dole and Del Monte. And the brand is still everywhere in the United States.

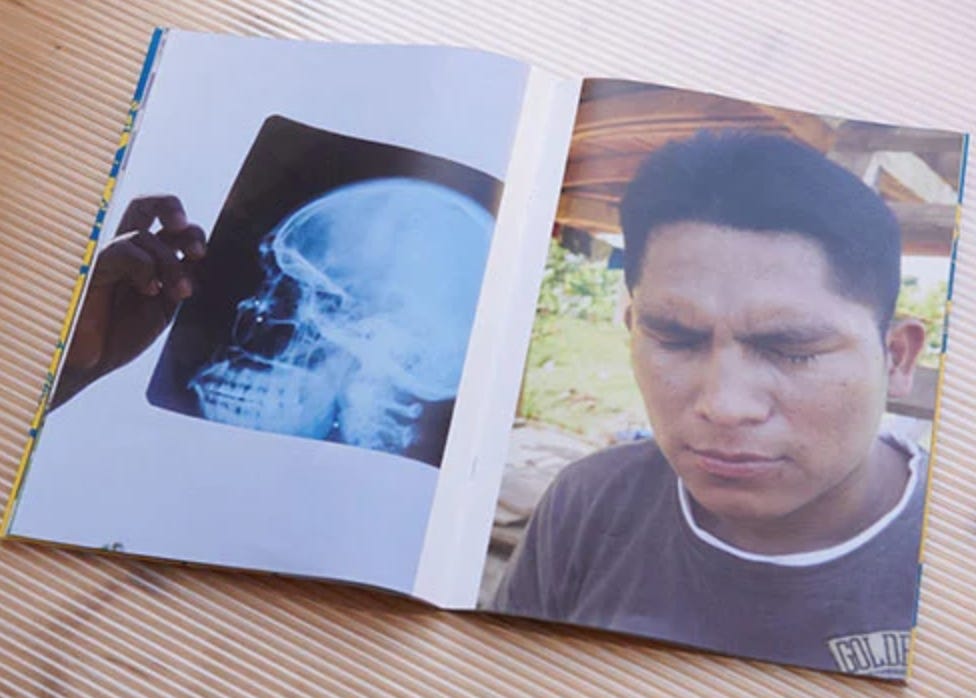

Everything has changed and much has remained the same. Workers on banana plantations are among the most exposed to the harmful effects of pesticides and to the very high risk of contracting tumors, liver problems, infertility and damage to the nervous system.

They’re also the ones who, on average, continue to earn the least, between 5-9 percent of the total value of the bananas, while retailers manage to grab between 36-43 percent.

The violence against workers and trade unionists has never really stopped. What happened in the last century continues to happen today, in an almost identical way.

In Panama, on 8 July 2010, the then president Ricardo Martinelli ordered the violent repression of the strikes called by the unions in the banana sector, who were fighting for higher wages and against the so-called ley chorizo, a law that would have limited the right of strike.

Two union workers, Antonio Smith and Virgilio Castillo, were killed in the clashes and over 700 workers were injured, many of them permanently—some were completely blind, others, luckier, only suffered serious eye injuries.

The story’s plot sounds familiar—banana plantations, striking workers, a government that defends Chiquita’s interests, violent repression.

In June 2024, a US federal court issued a landmark ruling against Chiquita, which was ordered to pay compensation to the families of eight men killed by a Colombian paramilitary group that the company had financed between 1997 and 2004.

It’s an important piece of this story, but not yet the one that will mark its end. A small element of hope in a story of injustice, oppression and greed.

Jungle capitalism

United Fruit insisted on low taxes and deregulation, exploited its labor force, abused its environmental resources, insinuated itself with the politically powerful and falsely proclaimed its social responsibility well before others recognized these tactics to be so-called corporate best practices.

In the Epilogue to Bananas, Peter Chapman concludes that as globalization has taken hold in the post-Cold War era, the ‘Banana Republic’ way of life has increasingly become the norm, with profound (value) consequences for us all.

Allergies is the reason why I don’t eat bananas. But as I looked into how tissue-cultured plants on banana farms are grown in test tubes to ensure uniformity. And the fact that they require an enormous amount of pesticides.5

However, this summer, the Olympics will source 3 million bananas, that’s how much “the culinary team at Olympic Village think they’ll need over the course of the Olympic and Paralympic Games, which take place over two weeks.”

Apparently, they’re the favorite food of athletes. That’s bananas!

I highly recommend the two books in the reference section.

References:

Chapman, Peter, Bananas: How the United Fruit Company Shaped the World (Canongate U.S., 2009)

‘La dittatura delle banane: come la United Fruit Company ha distrutto l’America Latina,’ Camilla Capasso, Lucy sulla cultura (July 9, 2024)

‘When the United Fruit Company Tried to Buy Guatemala,’ Olúfémi O. Táíwò, The Nation (December 2021)

‘The shadow of the United Fruit Company still reaches across the globe today,’ Michael Fox, The World (March 2024)

Kinzer, Stephen; Schlesinger, Stephen; Coatsworth, John H., Bitter Fruit (David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, 2005)

Gasparotto, Carlos, Banana (Self-Published, 2023)

‘How to Feed the Olympics,’ Jaya Saxena, Eater (July 3, 2024)

Peter Chapman was brought up in London. He was a correspondent for Latin American Newsletters, the Guardian and the BBC in Central America and Mexico. He works for the Financial Times and lives in London.

You can find that letter here.

Here’s the fairly plain ad.

Justification of the coup required a pliant individual to take power. After much deliberating, the CIA settled on Carlos Castillo Armas, a disgruntled former solider turned rebel. He was backed by the US's Flying Tiger squadron and the governments of Honduras and Nicaragua, both ruled by US-puppet dictators. All of this was supported by covert propaganda campaigns, including setting up a rebel radio station, using the US embassy in Guatemala City as a covert operations base, and fudging the press back in the US.

The coup, carried out in 1954, was almost a failure, but was eventually successful, with Arbenez fleeing to Mexico in exile. Armas took power for three years, before he was assassinated, and replaced by a string of dictators in the short run. Armas' time in office was marked by corruption, authoritarianism, and the use of death squads on labor and peasant interests within the country.

Kinzer's book is a blow by blow account of the coup, and the key players involved in setting it up, as well as the reasons why it happened, in theory to combat communism, in reality, to help United Fruit avoid paying taxes or having to help build the Guatemalan economy.

Costa Rica’s banana industry is heavily reliant on chemical pesticides that threaten the environment and public health.