Food Culture — Part 2 of 3

How nutrition shaped humanity. What we eat determines how long—and how well—we live.

Beyond sustenance—a mini-series on the value of food to culture. Free subscribers will continue receiving post previews and trivia. Paid subscribers will receive the full articles and (re)sources. Thank you for supporting this work!

If you’re interested in the topic of culture and food, consider becoming a supporter. This 3-part mini-series will run in the next few weeks.

Everything comes with labels these days. That is especially true of food. But labels can be deceiving. Ingredients are written in type that is too small, marketing highlights 1 feature. ‘Fat-free,’ ‘sugar-free,’ ‘low-calorie,’ ‘low-sodium,’ may hide ultra-processed.

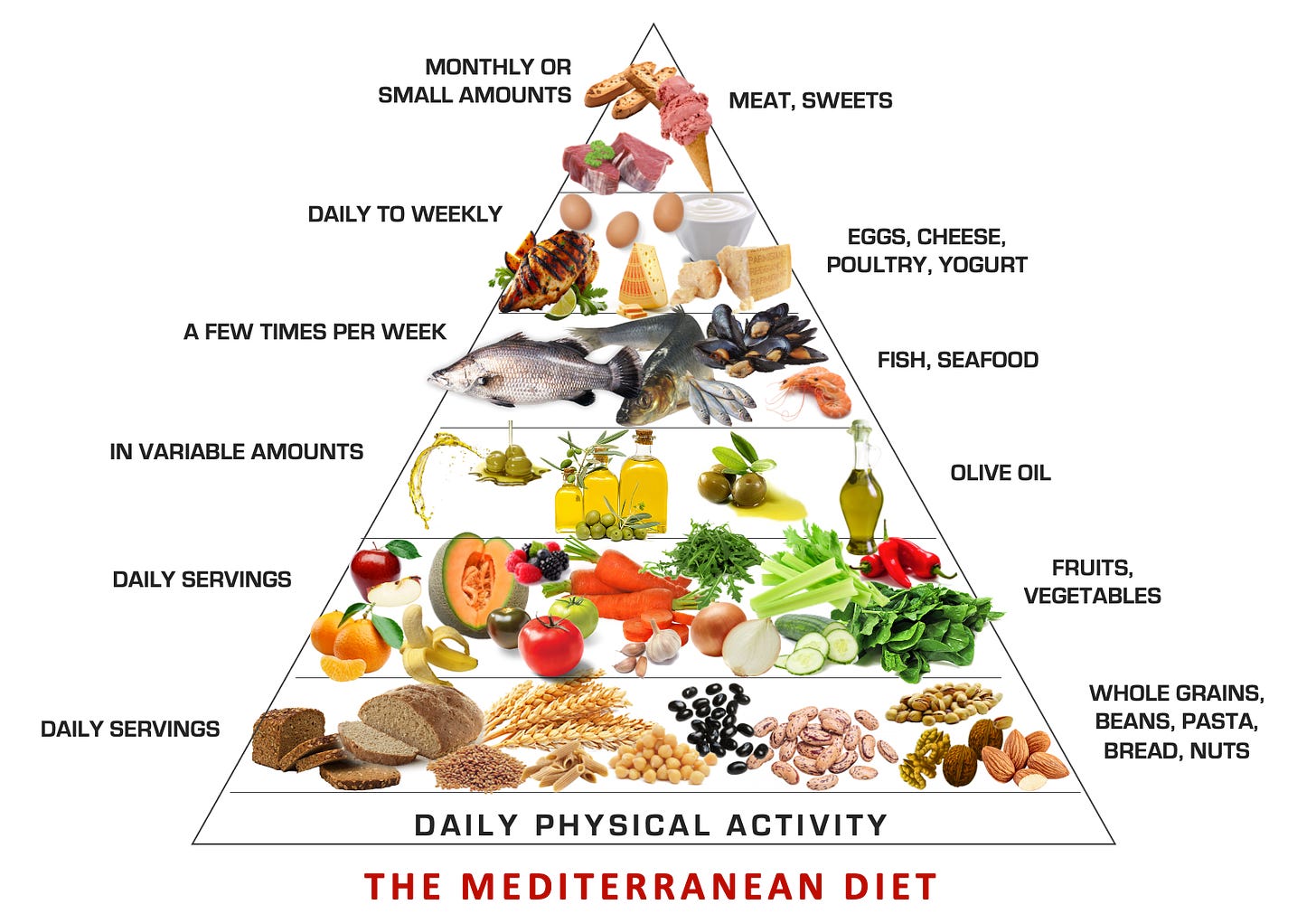

It seems easier to classify foods as ‘good’ or ‘bad.’ In the long run, however, this leads to problems. Given how much carbs are vilified, not all carbs are equal. In fact, it is the refined stuff—the white flour the nobility so loved—that is bad in large quantities.

There are good and bad carbs. As there are good and bad proteins, and good and bad fats. Food for thought—all the populations who have record longevity have a high carbohydrate diet.

All of them. No exceptions.

But before we surround ourselves with the pleasures and benefits of a balanced and nutritious diet, here’s the key to the film and book trivia from I promised in the first installment of this mini-series.

Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (1971) by Mel Stuart

La Grande Bouffe (1973) by Marco Ferreri

Eating Raoul (1982) by Paul Bartel

Mystic Pizza (1988) by Donald Petrie

When Harry Met Sally (1989) by Rob Reiner1

Goodfellas (1990) by Martin Scorsese

Like Water for Chocolate (1992) by Alfonso Arau

Eat Drink Man Woman (1994) by Ang Lee

Big Night (1996) by Stanley Tucci, Campbell Scot2

Ratatouille (2007) by Brad Bird

Julie & Julia (2009) by Norah Ephron

The Trip (2010) by Michael Winterbottom

How did you do with your guesses? Some of them were hard, but now you may have found some good movies or books to read.

My disclaimer—I’m not qualified for, nor providing any advice, health or otherwise, about food. But I do have strong opinions about nutrition.

Imagine two young people who want to get married. Now visualize it between 1628 and 1630 in Lombardy during Spanish rule. But not everyone agrees Renzo and Lucia should be married.

The story begins with Don Abbondio, curate of Renzo and Lucia’s town in charge of celebrating the wedding of the two young spinners. Under pressure from Don Rodrigo, the lord of the town, the priest starts postponing the celebration.

This is the premise for one of the most famous novels of the 19th century: The Betrothed. Alessandro Manzoni wrote it in 1827 and published it between 1840 and 1842. What’s notable about the book, is that it’s the first example of a historical novel in Italian literature.

Research went into the book—both the story of the nun of Monza and the Great Plague of 1629-1631 were based on archive documents and chronicles of that era. Compared to previous literature, Mazoni’s historical novel addresses the theme of hunger and the related theme of food with seriousness and dignity.

Manzoni recounts the agony of a humanity deprived of the raw materials of life. Along with hunger, we read of unlikely recipe books with dishes based on rice bread mixed with barley, rye and vetch, bitter meadow herbs, tree barks seasoned with a little salt and poor-quality water.

There are many episodes in the novel in which Manzoni uses food to give body and blood to the characters and scenes. His knowledge of the rural world and of Lombard peasant civilization is in-depth and Don Lisander doesn’t miss a single detail.

The menus of the taverns that Renzo visits during his adventures are not random.

At the Full Moon tavern, they serve him a stew.

Made up of pieces of stewed meat, cooked over a low heat in a well-closed terracotta pan, the stew had the advantage of being an always ready dish, easy to keep warm among the embers, which benefited from prolonged cooking because it made it soft.

Low quality meat, the main ingredient, was tasty. Cooked in a sauce, stew goes well with bread. The village innkeeper’s meatballs were also a dish cooked with leftovers from boiled meat (with the addition of other poor ingredients) and have the advantage of being able to be served cold.

In the Milanese area they’re still a typical dish. It’s retained the ancient name of mondeghili. In the Lecco and Bergamo areas, pork loin rolls with a sausage-based filling are also called meatballs. Prepared when the animal was killed, they were preserved immersed in their cooking fat in terracotta wine skins so that they could be simply reheated at the appropriate time.

In Part 1, I included a brief review of the history of food and meals, that of the places where we eat, and the connection with culture.

Then, in Part 2, I’m switching more firmly onto the benefits of a balanced and nutritious diet to society, customs, and interesting experiments to test value.

Part 3 will be a historical review of how we brand, package, market, and sell a promise to make it the most appealing, with selected foods from Northern Italy and Europe—including my favorites.

Let’s savor the enduring connection between food and life.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On Value in Culture to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.