We stink at listening. That’s because we equate ‘to listen’ with a loss of control. It’s about ‘me’ and how someone else perceives us, not how we can serve the other. Any given conversation there’s more focus on competition than learning.

A study by mathematicians found the human brain has the capacity to digest as much as 400 words per minute of information. For reference, a speaker from New York City talks at about 125 words per minute.

That could mean that three-quarters of our brain is doing something else while someone is speaking to us. Children listen better. Do adults have too much brain power or not enough patience?

Reminder: You can get extra insights—in-depth information, ideas, and interviews on the value of culture.

Join the premium list to access new series, topic break-downs, and The Vault.

Listening has become a rare skill in our culture. It’s another one of those non-material things of value that we overlook.

I should mention that the authors of the study found women beat the pants off of men—at least, to a statistically significant degree. But men are fairly self-aware. They indicated they were average or below-average listeners consistently.

Could that be the main reason why women speak twice as much? When you have to repeat everything at least once…

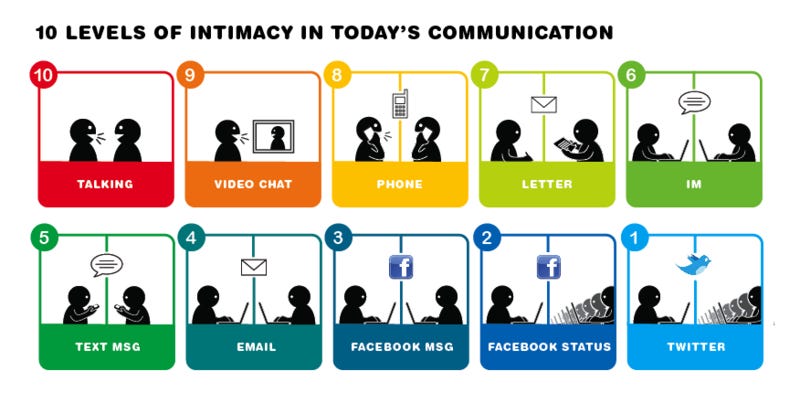

Distractions can have devastating consequences. The National Safety Council estimates that cell phone use and texting while driving cause 1.6 million accidents per year.

In a world that has become mostly visual and written, we’re losing the ability to pay attention to what we hear so we can respond to what’s happening in new ways. Instead, we react to situations based on memory because we aren’t aware of what we think.

In other words, we hear, but we don’t listen. Semiotician Roland Barthes explains the distinction between the two—“Hearing is a physiological phenomenon; listening is a psychological act.”

Hearing is always occurring, most of the time subconsciously.

In contrast, listening is the interpretative action taken by the listener in order to understand and potentially make meaning out of the sound waves.

Listening can be understood on three levels: alerting, deciphering, and an understanding of how the sound is produced and how the sound affects the listener.

Although most of us acknowledge the importance of listening to improve our understanding, learn new things, and enjoy new experiences, when it comes to the act itself we fall short.

This is probably because nobody teaches us how to listen explicitly. We are born, develop a sense for what is dangerous in our environment, then fine tune our ability to turn off some of the stuff we find distracting.

But we don’t learn how to turn off our thought process and memories to have a direct experience of what happens in real time. And we cannot respond to new situations when we hold onto what we may remember happening in previous ones.

In conclusion…

At a company where I worked we used to say that when the head of sales—who was a chronic late joiner for meetings—walked in the room. I say that with tongue in cheek, but that’s what we do, we jump to the end and skip the important bits.

William Isaacs, founder of a renowned strategic dialogue and leadership development firm, says, “one of the ways we sustain the culture of thinking alone is that we form conclusions and then do not test them, treating our initial inferences as facts.”

Which may be one of the most common reasons that prompts us to notice that history repeats itself. To illustrate the dangers of basing our thinking on a personal assessment and not direct experience Isaacs recalls the Cuban Missile Crisis.

“Some thirty years after the Cuban Missile Crisis, several academics brought together the Russian, Cuban, and American leaders in charge at the time of the crisis to reflect on the causes of this near-devastating conflict.

A series of three meetings were held in Boston, Moscow, and Havana. Included on the Russian side were Ambassador Dobrynin, Soviet Foreign Minister Gromyko, and son of Nikita Khrushchev, and the Soviet generals responsible for installing the missiles in Cuba. American participants included Robert McNamara, Ted Sorenson and other members of Kennedy's inner circle, and for the Cubans, Fidel Castro himself.

Simply getting these leaders together was an important step toward greater dialogue about international conflict. Their meetings revealed some important facts not previously understood or well known, and shed light on the disastrous consequences of drawing conclusions.

One important component of this crisis was the fact that the Cubans installed missiles without notice ninety miles off the coast of the United States. A U-2 spy plane caught sight of these and noted one striking fact: There was no camouflage on them. It seemed to some in Kennedy's inner circle that the Soviets were aggressively moving forward, not even bothering to camouflage their missile installations.

Thirty years later another side of the story emerged. As it turns out, the Russian army, which installed the missiles, was accustomed to installing missiles in Russia, where there was no need for camouflage. Like any good military bureaucracy, when ordered to install missiles in Cuba, they did it the way they normally did: without camouflage.

Some three decades later in conversation, the Russian general in charge of the installation made it quite clear that there was no ulterior intent in leaving the camouflage off. What was taken by some as clear evidence of aggressive intent was essentially based on an erroneous presumption.”

When we draw abstract inference from our experience, we miss new data. But that is not all. When we jump to conclusions, we then progress from the conclusions to assumptions we make about subjects, and adopt the results as beliefs.

Once we get to the belief stage, we entrench ourselves into a position, thus making it much harder for us to change our stance. In this sense, beliefs are limiting. We can improve the quality of our inquiry if we pay attention to the actual evidence

That needs to happen before we make a decision.

We can find what's missing

Can we overcome automatic patterns we’ve contributed to over time? What can we do to become more pragmatic about our actual experiences? What should we do to improve our listening skills?

I’ve used all of the tactics below with some degree of success.

Slow thinking

It isn’t easy to pay attention to how we listen. The landscape of our memories is filled with things we can recall readily—sometimes painful stuff. ‘Disturbance,’ from an emotional situation that happened in the past, for example, usually leads us to listen in a way that is self-confirming—we look for evidence that we’re right, others are wrong.

Disprove

We can learn to use discomfort as a lever to look deeper into its cause. That can help us see what we’ve missed. Are we the source of the difficulty? Is there a memory of a similar situation that occurred in the past that we are imposing on others who were not part of it? We can listen in a reflective mode and begin to see how others experience the world.

Mind the gap

Do we walk the talk? Do we do what we say consistently? Have we examined our actions to see if we’re the source of the problem? No one acts consistently with their words. Some of us are more aware than others of how large this gap is, how systematic it is.

Notice resistance

We can learn to observe our reactions to what someone else says, but also keep some distance between us. Do we project our opinions onto them? Is our distortion shield on to protect ourselves from new information? There might be an almost irrepressible tape in our mind that plays, especially when we react to a person.

Stand still

There’s an expression recruiters and managers still use—to hit the ground running—that does everyone a disservice. We’ve not cultivated the ability to pause. Yet, when we quiet our mental chatter and busyness, that’s when we’re able to let information sink in. We may even be more relaxed. Calm on the water surface of our experience can help us see below to the depths.

A world of possibilities

When we’re in a hurry, we should slow down. It’s a piece of advice my mother gave me a long time ago—it works. It was probably something her mother taught her. There is a reason why popular sayings stay popular. They’re a simple synthesis of hard-earned wisdom.

Poet David Wagoner captures the advice a Native American elder gives a child lost in the woods, “Stand still, the trees ahead and the bushes beside you are not lost.” We can find our way when we take our place as part of it —by staying still, noticing resistance, minding the gap, looking to disprove, and thinking slow.

It’s hard to listen, but it’s the single act that can open so many new doors and possibilities. A non-material thing that has value.

References:

Sullivan, Bob and Thompson, Hugh, The Plateau Effect (Dutton, 2013)

Barthes, Roland, The Responsibility of Form: Critical Essays on Music, Art, and Representation (University of California Press; Reprint, 1991)

Isaacs, William, Dialogue: The Art Of Thinking Together (Crown Currency, 1999)