The Art of Talk

It's impossible to have good conversations without learning to speak and to listen well.

“My tongue was stuck to the roof of my mouth,

I couldn’t swallow,

I had cold chills.”

Said many who are about to make public remarks. ‘Speaking in front of an audience’ remains one of the top fears Americans list—along with loneliness, and ahead of death (though ‘going broke’ is a strong contender.)

If you feel that the act of standing up alone is a set up for being rejected you are not alone.

People would rather labor over a social media post, an email, a text, over being in front of a group of expectant faces. Which is interesting, because something you write or read has more permanence that something you speak or listen to. The latter are fleeting, ephemeral, more akin to performing arts.

For this reason, I find talks exhilarating.

I’ve done many all over the world in front of groups large and small for more than a decade. Each talk gave me something special. The people who lined up to speak with me afterwards sounded energized. At one particular talk, I met a young professional with whom I ended up spending the rest of the day talking and walking around the conference. We still touch base periodically.

Those kinds of connections are precious and I value them.

I’ll get to structure and examples you can use to improve your presence later in the article. For now, at the risk of stating the obvious, let’s agree that when you write, you can edit before you post or send—with or without the help of others. Some email programs even allow you to unsend a message should you feel remorse.

There’s a feeling of control with writing. Though we know from social media fiascos that’s not (entirely) warranted. We all have examples of a post that suddenly gets noticed for all the wrong reasons.

Public speaking has played an important cultural role in human history.

Confucius believed that a good speech should impact individual lives, regardless of whether they were in the audience. From Plato to Cicero to Galileo Galilei, many books on philosophy and science were written in the form of dialogue.

We don’t just want to talk, we want to persuade, change minds, if not hearts. To create something of value—an impression, a feeling of trust, a connection—speaking follows a different process than that of writing.

Over reliance on writing is hurting our ability to speak.

When we write we learn to distance ourselves emotionally. At least long enough to produce something coherent (do keep those drafts in your email folder to reread before sending.) It’s much harder to check emotion in real time, as we receive reactions—a shift of the body, someone walks out of the room.

The truth is that delivering an impromptu address is a hard-earned skill. But we can prepare for talks. And that can help us improve our more private conversations. We can write out what we want to say ahead of time. We can practice to use emotion.

Spontaneity is much easier when it’s planned.

Issue or argument at the core

Talks have secret lives.

The more spontaneous the speech or presentation, the more prepared the speaker. I’m looking at corporate 90-slide decks squeezed into an hour of time. That is insane. Don’t do that. Figure out what your point is first.

Mountains of preparation work go into driving a point home. Share the slides as research material, if you want. But start with an abstract. Ideally the abstract clarifies an end goal and provides some message. Within it, you could have techniques or points, each to break down into elements.

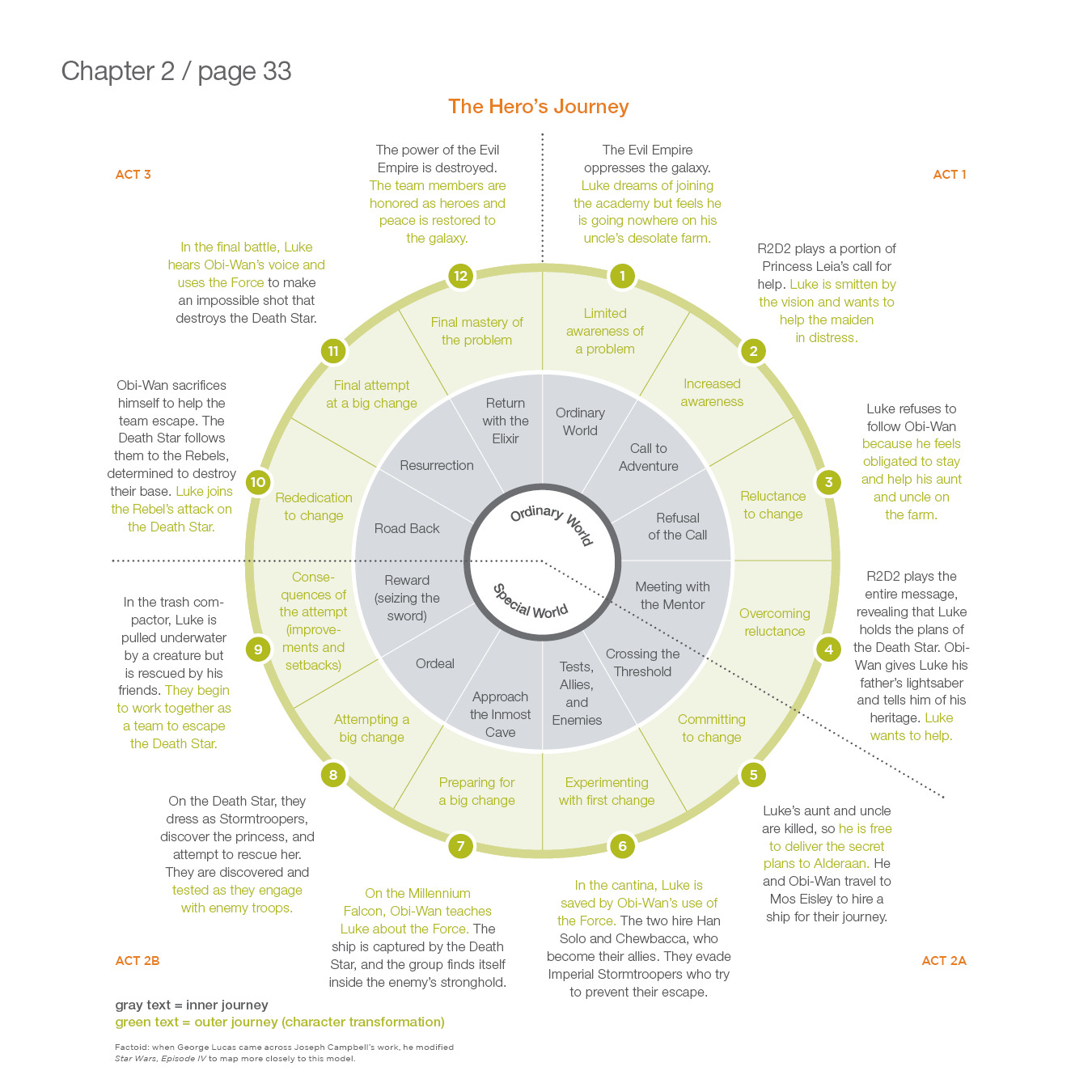

We use stories to illustrate our points, and use a narrative arc to keep the listener’s interest throughout. Stories convey meaning and resonate with people. Your audience is the hero, not you, the presenter. Stories should have:

A clear beginning, middle (this is where the development and conflict builds) and end

An identifiable structure

An incident (turning point in your presentation)

Myths, screenplays, and movies are structured that way. The structure glides over skepticism and resistance and wins us over. There’s a certain tempo to the story that engages us in an internal conversation. That’s what you want in your talk.

At this point, most presenters go ahead and prepare a deck out of an outline, but there is tremendous value in holding off on the deck until we write the entire speech—just like we would when delivering an address.