How to Write for the Next Millennium

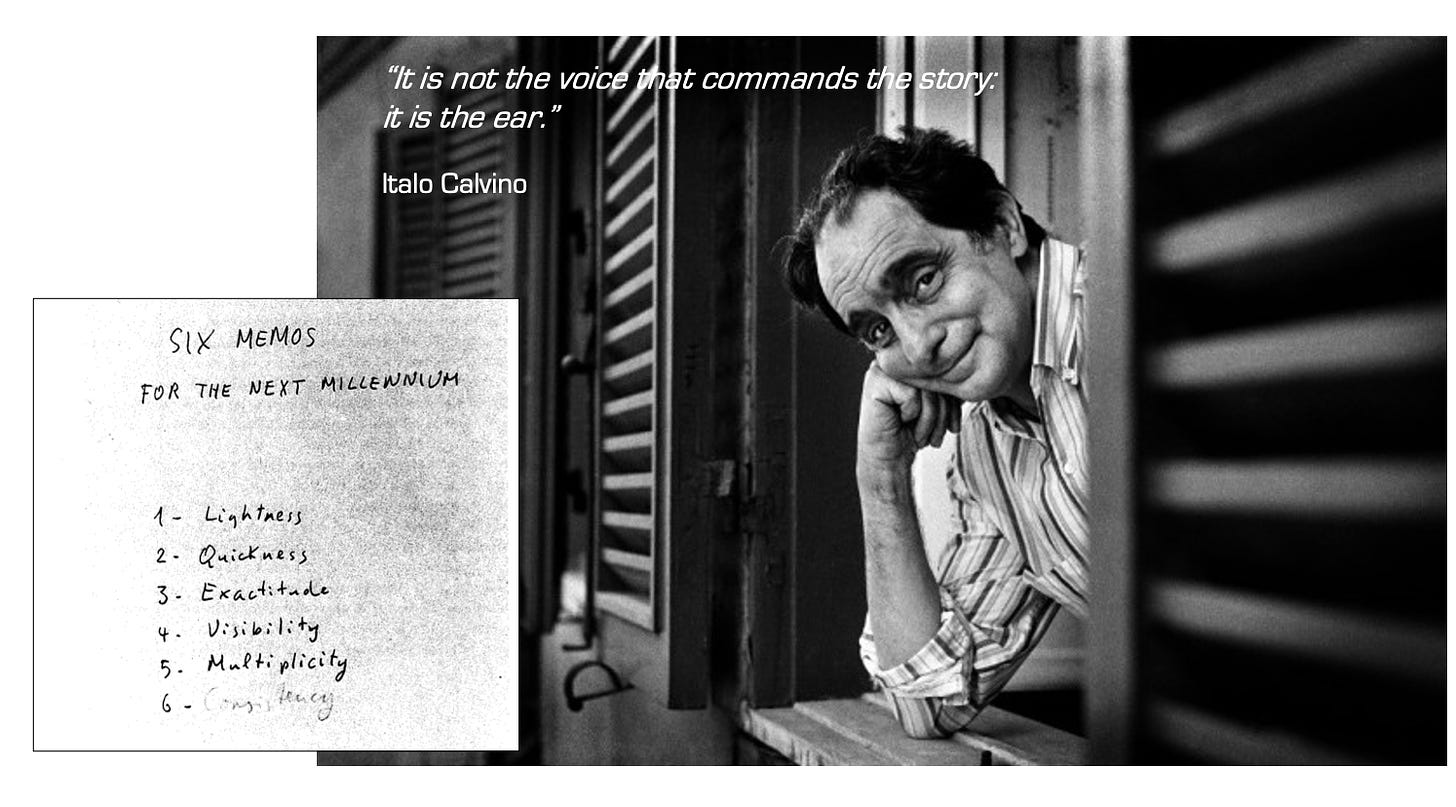

Behind Italo Calvino's magic curtain on literary value.

When Calvino talks about literature, he talks about my literature, his literature, everyone’s literature and the literature that doesn’t exist, and that maybe will exist or maybe not—he put in a good word.

Sig C talks about a literature as ethereal as perfume and as concrete as bread, and I love him. Calvino is a literary philosopher. He’s always striven to provide an alternative view to see through this world, to decipher its beauty and secrets through the lenses of imagination and fantasy.

On a public occasion someone asked him to name three talismans for the art of living deduced from experience.

“First, every now and then try to solve some quadratic equation. Then, repeat some poems you learned by heart as a child. Third, at least once a day remember that you could disappear at any moment.”

Math, poetry, and philosophy—memento mori. Three things I loved about his work as a writer, essayist, and moralist—in symmetry with his three pieces of advice—made an impression on me as a young reader and then as a writer:

The wonderful denunciation of the madness of normality contained in The Baron in the Trees—with that child who refuses to live on the ground, among adults, and takes the path of the trees forever.

The ability to make the assembly of a possible novel a novelist work itself with the ten stories begun in If on a winter’s night a traveler.

Finally, the prophetic acuity of the posthumous ‘American Lessons,’ in which he was able to harmonize rationalism and imagination, his two wings.

100 years ago

He was born Italo Giovanni Calvino Mameli on October 15, 1923 in Santiago de Las Vegas, Cuba. The eldest son of Italian botanist Mameli and her agronomist husband. The family returned to Italy after his birth. They divided their time between the father’s planting station, in the seaside town of San Remo, and a country home sheltered by woods.

Calvino seemed destined to spend his life grafting one marvelous thing onto another when he enrolled in the agriculture department at the University of Turin, in 1941. But when the Germans occupied Italy two years later, he left school to fight in the Resistance.

The experience colored his first published stories, which were about war and the horrors of the modern world. After Italy’s Liberation he enrolled in Literature in Turin and graduated in 1947. He sold books to Einaudi publishers on installments.

By the fifties, the horrors of the war turned into fables, fairy tales, and historical fictions. “Fairy tales correspond to profound needs for emotional and imaginative learning: it is not for nothing that they refer to initiation rites.”

“Fairy tales correspond to profound needs for emotional and imaginative learning: it is not for nothing that they refer to initiation rites.”

Through a grant by the Ford Foundation, in 1960 he spent six months in America. He met Argentine translator Esther Judith Singer—Chichita—in 1962. They married in 1964 in Havana. Sig C divided his time between Turin, San Remo, Rome, and Paris.

Calvino distanced himself from politics in the mid-sixties. He defended his decision to withdraw into literature in a letter to Pier Paolo Pasolini. “I spend twelve hours a day reading, on most days of the year.” It was 1973, the beginning of his travel reports.

His travels took him to Iran, the United States, Mexico, and Japan. “I always stay a bit in the air, I’m in cities with only one foot.” Of science he liked the possibilities for stories. “Every axiom is a story.”

He was enamored with the craftsmanship of writers who came closest to the oral telling and retelling of tales to create an “infinite multiplicity of stories handed down from person to person.”

The wildly diverting, episodic approach to storytelling of Ariosto, Boccaccio, Cervantes, and Rabelais appealed to him. Calvino sought to reclaim the bond between intricate narrative and entertainment.

How to write for the next millennium

Sig C spent the summer of 1985 in Roccamare preparing a series of conferences he was to deliver at Harvard. Struck by a stroke that killed him, Six Memos for the Next Millennium became his posthumous ‘American Lectures.’

Coming from his pen, this is not a straightforward guide to writing. There are no chapters on plotting and point of view or the use of commas and semi-colons. What you won’t find in this book are lessons on grammar, editorial tips, or the best way to market your book to the masses using obnoxious tactics.

Instead, the book puts forward a useful set of values to help literature survive. So that it can continue to help us know-why.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On Value in Culture with Valeria Maltoni to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.