Between dream and reality

Could the documentary-fiction hybrid art format be the key to gain access to new energies?

Too often we get busy with our day before we have a chance to wake up properly. That state—not quite dream, not yet awake—is gold.

Before we’re in the clutches of our rational mind we can partake of a bigger stage. One without ego, where our knowledge multiplies. Sleep, perchance to dream, that’s where we elaborate. The transition phase to reality is where we ‘see’ and ‘feel’ better.

Many don’t benefit from the gifts of psyche.

Ancient Greek culture understood and respected its house. They had myths to use for reference. We still have myths, but our cultural narrative worships productivity—‘get up and get going right away.’ We rush to produce, spend, consume.

Reminder: You can get extra insights—in-depth information, ideas, and interviews on the value of culture.

Join the premium list to access new series, topic break-downs, and The Vault.

By my measure, our society has lost its connection to the value in culture. The cuts to art, drama, dance, music in public education keep coming. All the things that make a country great, gone from the curriculum.

The quest for individual perfection—more in form than in substance—has replaced the group as fulcrum of our identity. Make no mistake, cults bank on this shift from love and sexuality to aggression. Then we wonder why birth rate it down.

Cultural programs also face massive challenges in cities and states—both in America and Western Europe. In the best possible light, America sees the arts as fundamental for innovation—always the practical side. In Britain, the creative industries are a significant economic driver, a source of cultural value and of diplomatic soft power.

But they also know that they support individual well-being and social cohesion. This last bit was obvious throughout Europe during the pandemic. The cuts could be because knowledge and experience contribute to critical thinking skills.

Enter techno-science, objects that talk to each other, and algorithms to channel and control human behavior—a massive free-will crisis. To resist is hard. After all, we are social creatures and these ‘tools’ purports to be just that, innocent conduits.

Why are we so ready to give up the very things that make us human?

It’s hard to read books and essays after a habit of screens. It takes extra effort to go out to museums. It’s difficult to talk to people—never mind philosophers. Even online, lectures and independent films come second to the allure of quick memes.

We seek acceptance—dare I say love?—in all the wrong places. Hybrid forms of art could be the access to wisdom of old in new clothes. I see more examples of mixed formats where we can be both actor and principal, participant and observer.

And maybe that does the trick. It appeals to our rational narrative, while it connects with our emotional nature.

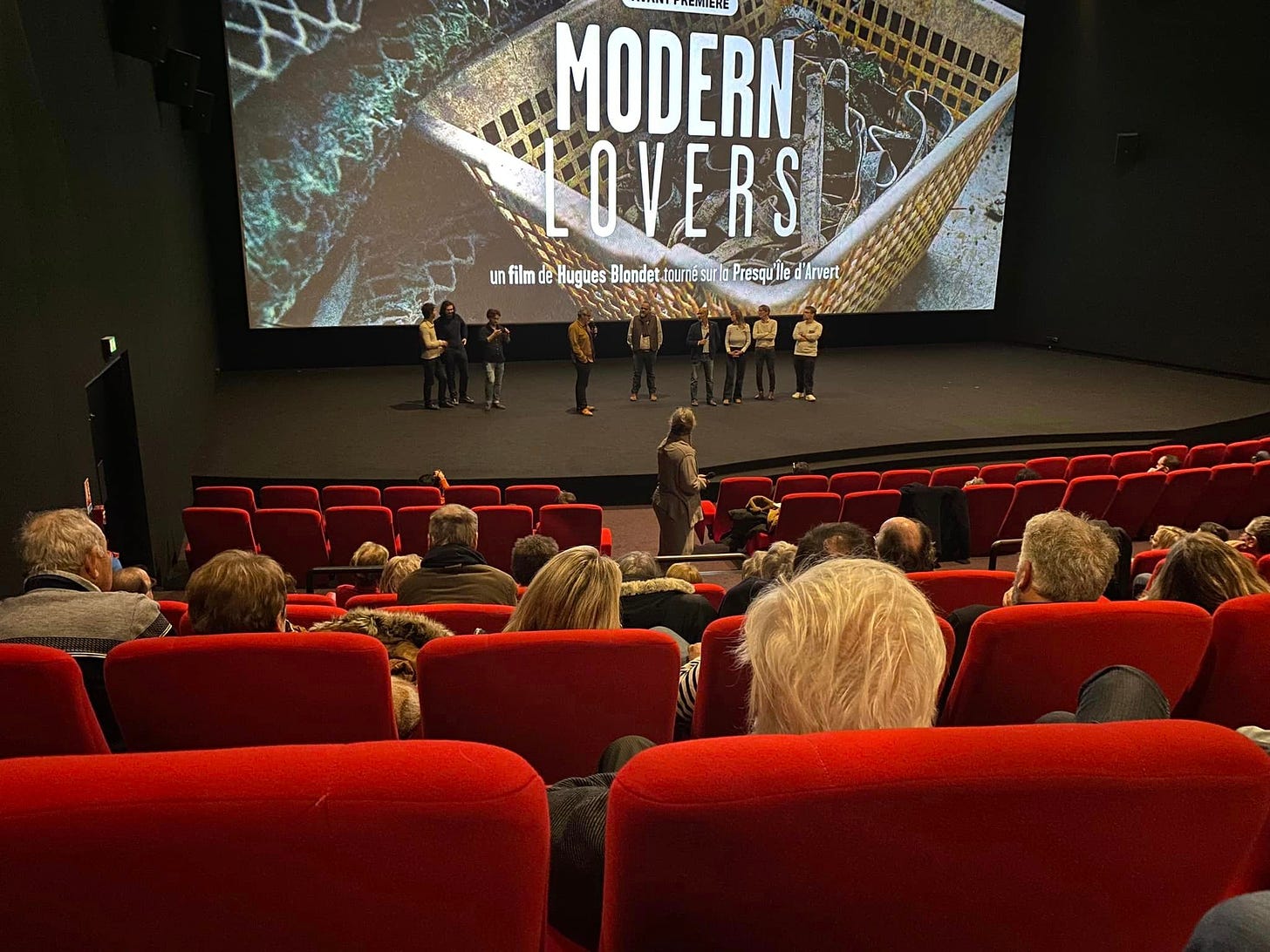

One such format is a film that premiered under the zinc and slate roofs of the École Normale Supérieure. The composite by director Hugues Blondet is a love story, which develops—slowly and without words—between two workers in the oyster industry, and an interview—filmed in Venice—with mathematician and biologist Giuseppe Longo, professor and researcher emeritus of the same École.

A constant presence of water landscapes and the theme of the opposition between mechanism and nature unites the two parts. The transition evokes a dream-state, but is not one—designed to question society.

Blondet is screenwriter, director, and producer. The child of television decided to create a hybrid, to mix a documented intervention with the romance that develops gradually in the film.

Algorithms and artificial intelligence shape society. Louis, the oyster worker, is obsessed with dating sites. The enigmatic woman he meets in real life works in a oyster hut. They’re in proximity to each other, but not in relationship, yet.

The fantastic oyster landscapes of Blondet’s memory (he worked there) represent the human element in the film.

“I wanted to bring something contemplative, something poetic by sublimating my childhood landscapes. For example, I filmed shots in a cabin in L’Éguille, on the banks of the Seudre, but also at David Jaud’s, an oyster farmer friend who goes to the markets, and at the Favier oysters in La Tremblade.”

Hugues Blondet, interview

Longo answers the question about life. He’s the important figure in a notion of science that is not the majority. Using the tools of mathematics and biology he wants to ensure that we recognize scientific development as organic, rather than mechanical.

There are countless unpredictable factors and surprising theoretical frameworks that intervene in science, he says. To be such, scientific development must also include ideas and aspirations, our thinking, our beliefs, and our bodies.

The interview is a historical look at the development of knowledge. It attempts to oppose the hubris, the arrogance, of the techno-scientific approach that considers science a necessary determinant of reality—predetermined and predictable because it’s completely calculable.

This vision includes an illusory and presumptuous perspective of artificial intelligence, which cannot be compared to the human mind in any sense. The techno-scientific approach has imposed a wrong vision of biology—we decode DNA to derive every development of the human being from it.

An enormous amount of money has been poured into this type of approach to molecular biology. In reality, however, we understand that we cannot predict mechanically what comes from DNA. Much depends on people’s history and habits.

We think we’re omnipotent, that’s the rub. And we give up critical and historical thought to favor numbers and statistics. They only seem concrete—but are instead abstract. So we derive consequences and directives without asking the anthropological question—what is the human being? What’s our place in nature.

From fact to fact, from necessity to necessity, we move towards a society that is increasingly controlled and pre-established by those who control the data.

Longo’s denunciation is interesting because it’s internal. Made with sophisticated tools of the same sciences, it proposes an innovative vision of the same subjects. He doesn’t suggest we abandon or condemn or downsize science and technology in favor of humanistic disciplines.

His—and the director’s—is a cultural question that calls us to review our knowledge, not fight ideology. But there’s a rift in our culture, which has fragmented society and is causing damage.

“A part of humanity seems destined for a profound cultural, epistemological, and even physiological transformation. But the speed of this change, favored in particular by information technology, jeopardizes our biological and emotional balance and tears apart the ethical and aesthetic components inherited from tradition.”

Giuseppe Longo, cultural evolution toward the post-human (Italian)

Love is the other part of the film. Even in modern times, in the digital age, love can be mechanical. One the protagonist seeks it that way at first. He dates a series of women met through an app with the same canned approach.

But love is emotion and biology, not numbers and statistics. The natural love with the inconspicuous, but intense, genuine, and elegant workmate arises in due course. For there is a process in relationships, as there is in science, which doesn’t make the one less true, and the other less effective.

Reminder: You can get extra insights—in-depth information, ideas, and interviews on the value of culture.

Join the premium list to access new series, topic break-downs, and The Vault.

Culture matters differently at different levels of human experience—family, friends, colleagues, neighbors, clubs, cities, regions, countries, and nations. Progress—physical and intellectual—has a social component. That’s where we access new energy.

The transition between the unconscious of dream and the fully conscious of our daily rituals, that’s what art replicates. So we can find ourselves in a new aesthetic and emotional state where we get a taste of the possible.

Each work of art is a dialogue between artist and epoch. What does the hybrid format say about ours?