Published n. 5: a yardstick for an act of pride

Commentary on our ability to communicate to one another.

Have you ever heard of the myth of Prometheus? Who among you doesn’t remember his gift to men—fire? It’s one of the most beautiful myths for young people to read, because in this ancient myth, apparently banal, there’s a great truth.

Not everyone knows that Prometheus also stole a chest from the goddess Athena. the chest held two precious things, two things that allowed man to survive for thousands and thousands of years—Intelligence and Memory.

Intelligence, from intus (inside) and legere (to read), literally means ‘to read inside.’ Not outside, not beyond, but ‘inside.’ It means a person who has intelligence knows how to look at the heart of things, knows how to grasp their hidden aspects.

Prometheus, however, also gave people memory. With this myth, the ancient Greeks tell us something very important—that intelligence without memory has no value. We use memory to treasure past experiences, but it makes sense only we transmit it.

Like a flame, memory goes from house to house, from generation to generation. Do you remember when Aeneas carried his father Anchises on his shoulders to help him escape from Troy? Aeneas apparently chose to save least useful thing—an old person.

But he did so because the elderly are the custodians of the memory of a people, our history. To understand the present, we must know the past. Memory is like a light bulb turned on in a room that had remained dark until that moment.

However, the Greeks tell us that memory without intelligence is useless. It’s of no use knowing that Socrates—the greatest philosopher of all time—was put to death by the Athenians, what really matters is understanding why.

Understanding that with his uncomfortable questions, he had become a ‘problem’ for the status quo. To understand how intelligent a person is we listen to the answers, but to understand how wise, we listen to the questions.

On Value in Culture is a reader-supported guide to the role of narrative, language, and art in how we organize, perceive, and communicate about reality. Support my work with a paid subscription.

1/6. Since the last round-up, On Value in Culture published:

Leaplings—Anything hatched on February 29 has a special meaning in culture.

(🔒) Mastery and Freedom: Mina—Few artists represent the cultural history of late twentieth-century Italy, fewer yet embodied the beauty and power of music with the freshness, irony, and curiosity she does—over sixty years.

The Experience of Having the Conversation—A quick reprieve before heading into the week.

(🔒) Understanding McLuhan—Media insights rooted in the world of a humanist.

(🔒) Value & inflation—How the structure built around creative products starves and imperils culture—and threatens the degradation of life.

Narrative Fallacy—We like stories, we like to summarize, and we like to simplify—to reduce the dimension of things. Followed by a special 2-part reflection on extensions of the concept for supporters.

(🔒) ‘To be’ and ‘to have’ in Value—Gianni Rodari on the hilarity and goodness of our mistakes—a permission slip to change our ways.

(🔒) Quality of Life—That’s what people say they want when they make a major change—what they mean is to re-connect with value and each other.

‘Groupthink’—How our desire for harmony and conformity results in irrational and/or dysfunctional decisions.

Digital Lives—We have stored everything, and saved nothing.

A reminder for supporters that they can access full articles and commentary at The Vault (🔒). Thank you for supporting the work on value.

2/6. More of my conversations about reading these days start with, ‘I don’t read, nor enjoy business books.’ Perhaps that’s also true for you. I read select non fiction books that fall under the categories of culture, science, and literature.

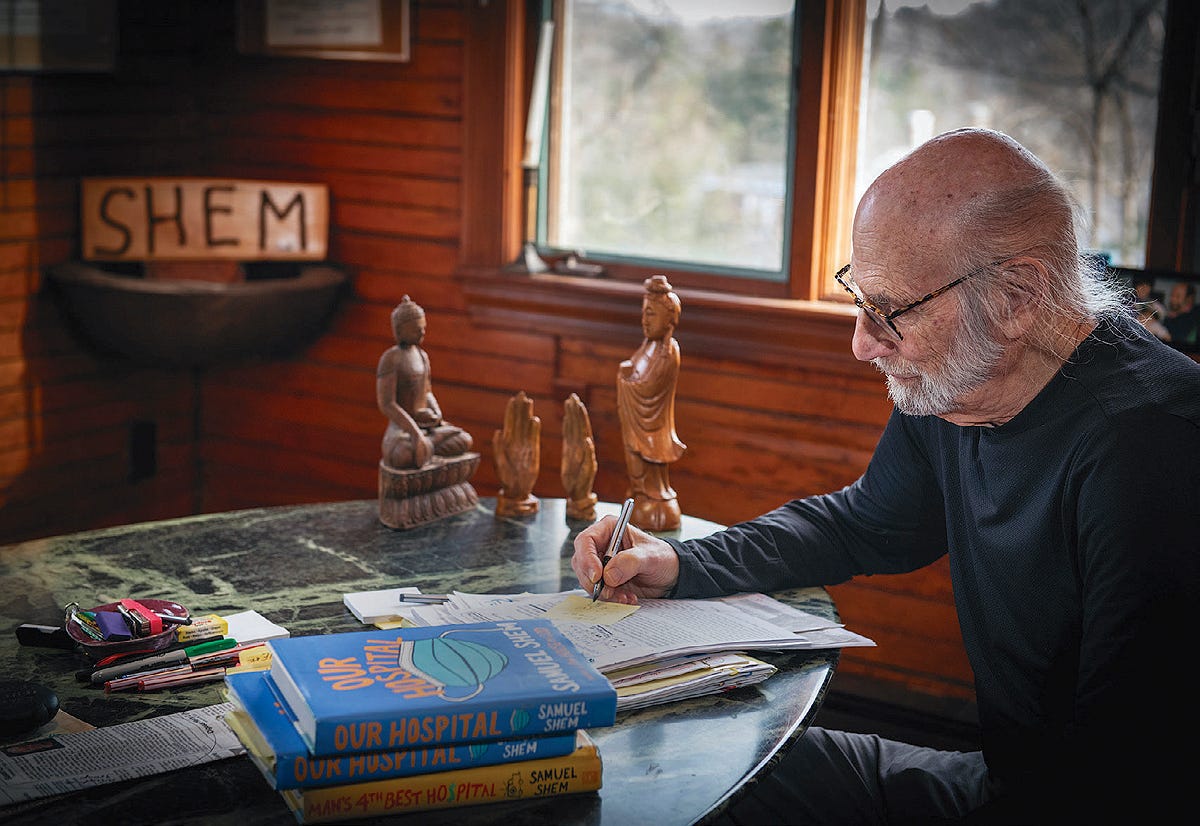

If you’re a writer, you cannot depend on writing for you meal ticket—you won’t be able to write what you want. Stephen Bergman understood that early on. He liked to write plays, poetry, fiction. Thus, he trained to become a medical doctor.

His next decision was to use a pen name for his fiction. In 1978, Samuel Shem published The House of God, a raw story mostly based on real people—interns and residents. For his honesty, Bergman/Shem is the Anthony Burdain of medicine.

The jokes Bergman and other newly minted MDs told each other in the off time became the fodder for his diagnosis by fiction. Though he wanted to be a playwriter, with help from an agent and a Putnam editor, he learned to write a novel.

The book frames ‘13 Laws of the House of God,’ most of them formulated by The Fat Man and introduced sequentially in ALL CAPS as the story unfolds. The Third Law, for example, is, ‘At a cardiac arrest, the first procedure is to take your own pulse.’

The Fat Man is there to guide Dr. Roy Basch, a new intern fresh off the BMS (Best Medical School) through the conflicts and dilemmas of medical practice (and occasionally non-practice and mal-practice.)

Some would call The Fat Man an anti-hero, a combination of a cynic and a humanitarian. The cathartic theme of the book is the conflict between death and life, love and hate.

“If I didn’t have your book, I’d kill myself.”

Intern on call alone all night at a veterans’ hospital in Tulsa, Oklahoma

“I really talk about the same thing everywhere: staying human in medicine. The danger of isolation, and the healing power of good connection, which means a mutual one.”

Dr. Stephen Bergman/ aka Samuel Shem

If you or someone you love is studyinge medicine, it will give them some comic relief. Because as Bergman later learned from his wife, health is “a relational entity in connection with others, be they humans, animals, or plants in the natural world.”

I just had my annual medical and my doctor told me that screens and money are the reason why she’s moving back into private practice. She wants to connect with people and not spend most of her time with admin work, billing as much as possible.

Both are themes on Bergman’s Man’s 4th Best Hospital, the third book in Shem’s quartet. Human beings deserve better than what they’re getting—in this case from the health practice turned into big business.

3/6. According to Elena Ferrante, “Writing is an act of pride.” Nicola Lagioia “Our singularity, our uniqueness, our identity are continually dying. When at the end of a long day we feel shattered, ‘in pieces,’ there’s nothing more literally true.”

In a conversation with Nicola Lagioia, Ferrante says “Human beings are extremely violent animals, and the violence they are always ready to use in order to impose their own eternal, salvific life vest, while shattering those of others, is frightening.”

The teaser for the new series from the latest novel by Elena Ferrante on Netflix trains the writer’s lens on the lying of adults. I think it’s exhausting to try to show a strong front, to try to keep things together—relationships, work, life.

Ferrante’s ideas on education converge with mine. I never once have been afraid when walking by a dark alley late at night that someone would pop out and say something insightful or intelligent to me. Imagination, a focus on creation lead to value.

“Will the contradictions of the educational system become increasingly evident, signalling its decline? Will education be refined and accessible without any connection to the ways we earn a living? Will we have more cultured diligence and less intelligence?

Let’s say that in general I’m captivated by those who produce ideas, rather than by those who comment on them. I’d feel better in a world of imaginative creators of grand ideas—even if this seems to me, admittedly, a formidable goal.”

Her thoughts on writing also resonate with me.

“I write to bear witness to the fact that I have lived and have sought a yardstick for myself and for others, since those others couldn’t or didn’t know how or didn’t want to do it. What is this if not pride? And what does it imply if not ‘You don’t know how to see me and see yourselves, but I see myself and I see you?’ No, there is no way around it. The only possibility is to learn to put the ‘I’ into perspective, to pour it into the work and then go away, to consider writing something that separates from us the moment it’s complete: one of the many collateral effects of an active life.”

More thoughts by and about Ferrante.

4/6. I just picked up the latest book by Sarah Bakewell. And immediately recalled the joy and companionship of her How To Live during the early days of the pandemic—a worthy re-read. Here’s a short interview with the author about that work.

It must have been serendipity that drew me to her Humanly Possible, right after I wrote my essay on the value of the humanities to connect with reality. In the introduction, which she titled ‘only connect!’, a line from E.M. Foster (Howards End.)

“We know and care about human things; they are important to us, so let’s take them seriously.”

I’d like to point out that we’re quite lucky to be able to live our humanist inclinations without much interference. Because in many parts of the world, people with humanist beliefs risk their lives. Pakistan is one such place where it gets personal.

In fact, the concept of people predates the term ‘humanist’—which became a practice of the nineteenth century. E.M. Foster’s 1910 novel explains that we should look to the bonds that connect us, rather than to divisions.

We should try to appreciate the angle other people have on the world as we do our own. It’s also a good idea to avoid self-deception and hypocrisy. If you’re a humanist, you live the life of the outsider, likely an exile and wanderer.

‘Free thinkers’ had to rely on their wits and words and conceal their thoughts from the Inquisition. They’ve been reviled, banned, persecuted, prosecuted, deprived of rights, and imprisoned. Religious and political conformists don’t like them one bit.

As human beings, we’re all tangled in each other’s lives.

“There lies before us, if we choose, continual progress in happiness, knowledge and wisdom. Shall we, instead, choose death,because we cannot forget our quarrels? I appeal as a human being to human beings: remember your humanity and forget the rest. If you can do so, the way lies open to a new Paradise, if you cannot,nothing lies before you but universal death.”

Bertrand Russell

We remain a work in progress, but with study and knowledge, we can do more. Humanists look to freethinking, inquiry, and hope as the three principles that guide their lives.

The first one underscores a preference to guide one’s life by moral conscience, evidence, social and political responsibilities to others—rather than dogma. Study and education serve to try and practice critical reasoning.

Hope for it is possible to achieve worthwhile things during our brief stay on Earth. We need freethinking, inquiry, and hope more than ever (because we live now, and want to make it count.)

Bakewell also talks about anti-humanists—fascists in Italy, blasphemy laws, today’s zealots of artificial intelligence—and reflects on the challenges that a turbulent 20th century posed to overcoming injustice through independent thought, moral inquiry, and mutual respect.

Humanists of the past allows us to see parallels to our own times and to see the value of being a little more human in our approach to things like work and relationships as well as collective traumas.

5/6. Perhaps access to our own thoughts is the reason why at certain points in history men burned books. So we can confuse going along with depth—even if we’re not fully aware we’re asleep at the wheel.

“Books must be opened, leafed through, dissolved in their presumed unity, to offer them to that question that does not ask ‘what does the book say?,’ but ‘what does this book make you think about?’

Books are not used to know but to think, and thinking means avoiding uncritical adhesion to open up to questions, it means questioning things beyond their usual meaning made stable by the laziness of habit; is to prevent the texts from becoming sacred texts for blessed consciences which, renouncing the risk of questioning, confuse the sincerity of adhesion with the depth of sleep.”

Umberto Galimberti, philosopher, The Opinion Game (1989)

6/6. A shift in words can make a big difference. When you go from ‘problem/solution’ to ‘possibility/obstacle’ in your narrative, you diffuses the stalemate between people or factions with power and authority.

“Stop trying to fix things,” says John Cutler, “write a new story,” instead.

“Your job, in effect, is to weave a story where people can still play the hero and protagonist of their narrative while at the same time getting people to row in the same direction, united by some common cause. Great leaders foster conditions where the ‘actors’ can shape their collective narrative instead of trying to own and micromanage it.”

Narrative plays a large role into positive impact. It refocuses everyone on a shared future, based on what everybody wants. Because of the confusion it creates, I don’t use the word ‘problem’ in my work anymore.

“Generally speaking, one does not find that people have considered the question of whether the word ‘problem’, with all that it signifies, provides an adequate description of what is going wrong in human affairs.”

David Bohm

The real work is in the questions. That’s where your own perspectives, intentions, and methods can converge—not in not-so-well-disguised attempts to fix individuals. But only in organizations that are open to collaboration—culture is the way we do things.

References:

Bakewell, Sarah, How To Live: A Life Of Montaigne (Other Press; Reprint edition, 2011)

Bakewell, Sarah, Humanly Possible: Seven hundred years of Humanist Freethinking, Inquiry, and Hope (Penguin Press, 2023)

Bohm, David, On Dialogue (Routledge; 2nd edition, 2004)