A study of life and the universe as a physicist-technician can imagine.

From microchips to consciousness and emotion—the four lives of Federico Faggin.

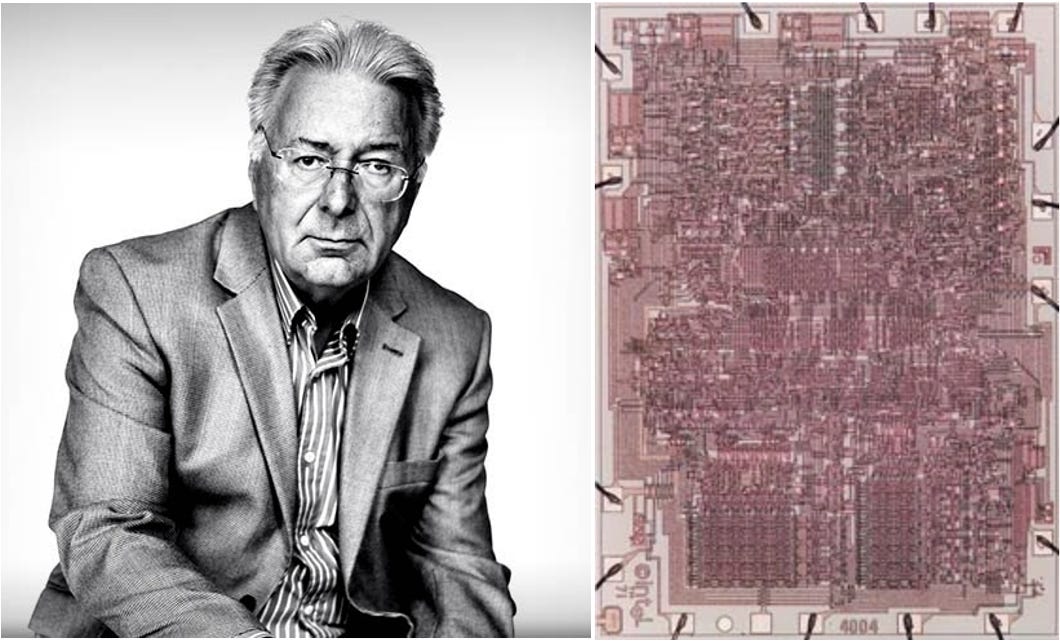

Many of the advances in technology today are largely due to the work of an Italian who’s lived in California for 16 years. He was the principal inventor and designer of the microchip used in the first commercial microprocessor, the Intel 4004.

That chip the size of a match head performs calculation and logical processing of information for which, not so long ago, we needed machines that took up the space of a room.

Physicist, engineer, inventor, and entrepreneur, in 2009 Federico Faggin received the National Medal of Technology and Innovation—the highest honor the United States confers for achievements related to technological progress.

He achieved everything he set out to do and more, was successful by all modern standards and culture, and yet… he was miserable.

Reminder: You can get extra insights—in-depth information, ideas, and interviews on the value of culture.

Join the premium list to access new series, topic break-downs, and The Vault.

Born in 1941 in the northern part of Italy he posed his parents a hard choice—to abandon the house in Vicenza, damaged by the bombings, and move as a precaution to a quieter town, Isola Vicentina.

His father, Giuseppe Faggin, taught philosophy at the Pigafetta classical high school. A professor who, in addition to the mysteries of Aristotle and Kant’s thought, taught the kids the values of life and human work, giving them the ability to criticize as well as study. Emma, his mother, was an elementary school teacher.

Federico inherited the curiosity and love for scientific speculation from his father. To the basis of all research he added his extraordinary experimental capacity. Attracted by the wonders of electronics rather than the abstractions of philosophy, he graduated from the Alessandro Rossi industrial technical institute in Vicenza.

In 1960, he began to work as a technician at the Olivetti electronics lab in Borgo Lombardo (Milan.) Faggin realized that to make his work operational in an industrial research lab he’d have to get a degree—acquire the basis of scientific culture.

He earned a doctorate in physics at the University of Padua with an experimental thesis in 1965. Faggin chose ‘an optical and electronic device to read frames of machines connected to nuclear experiments’ as his subject.

That earned him top marks and the ‘summa cum laude.’ Thus, he felt he had the tools to resume work in an electronics lab beyond a simple technician. He also taught as a university assistant for a few months.

But his world was that of industry—he wanted to develop equipment, machines, and systems for immediate use. So he joined a small company in Milan, Ceres. They were the years of the first calculators and very large and expensive machines.

“To give you an idea, the computer of an Italian bank occupied a surface of at least 300 square meters, requiring environmental conditions (such as constant temperature and humidity) that would require very expensive management.”

In 1966, he developed the first ‘thin film’ electronic circuits. They were the ancestors of today’s sophisticated chips. News of skilled of tech people travels fast in the world of electronics. And the managers of SGS in Agrate Brianza (the leading Iri group company in the integrated circuit sector today) offered him a research position.

Federico’s ideas and experimental skills quickly lead him to lead a group of young people who create the first integrated circuits in Metallic Oxide Semiconductors (MOS), semiconductors that exploited a new principle for their operation.

And from there the invitation to relocate to the operational heart of the company in the area between San Francisco and San José, California—the legendary Silicon Valley.

“I arrived in Silicon Valley with my wife, and we had to manage to live on a daily trip of just 12 dollars. After a few weeks we had to ask a friend for a loan to get by.”

But if money was scarce, the ideas were abundant.

“It was precisely in that period that I developed a new technology for the manufacturing of MOS integrated circuits, with performances enormously superior to those previously used. This technology was later adopted by all the multinational electronics companies. It was called Silicon Gate Technology. It allowed for an increase in both the speed and quantity of integrated devices, qualities that are the basis of modern microprocessors.”

Silicon Valley in 1970 was a very small place indeed. The fame of this researcher spread rapidly and Intel came calling. They offered Federico better conditions. “No, no salary increase, but a small percentage of the company’s shares: a thousand out of 2 million.”

The 4004 came from his new workshop. It was the first microprocessor with ‘words’ of four bits (the bit can take the form of zero or one and is the fundamental element of computer information.) To process ‘words’ of four bits means was 16 times faster.

From 1970 to 1974, Faggin designed and created over 30 types of highly integrated MOS circuits, from microprocessors to the new micromemories that are in every desktop calculator. The work group he directed included Americans, Japanese and Chinese developers.

Bitterness and disappointment first, then lack of flexibility led to new ventures

By chance Faggin discovered that one of his bosses had patented a good part of his ideas and original experiments. Someone who had claimed to be a sincere friend, too. The friend’s betrayal stung more than the value of the damage.

But he didn’t resort to courts or lawyers. Instead, he founded his own company. He and collaborator Ralph Ungermann left Intel. In an interview for Electronic News they said they intended to set up their own business.

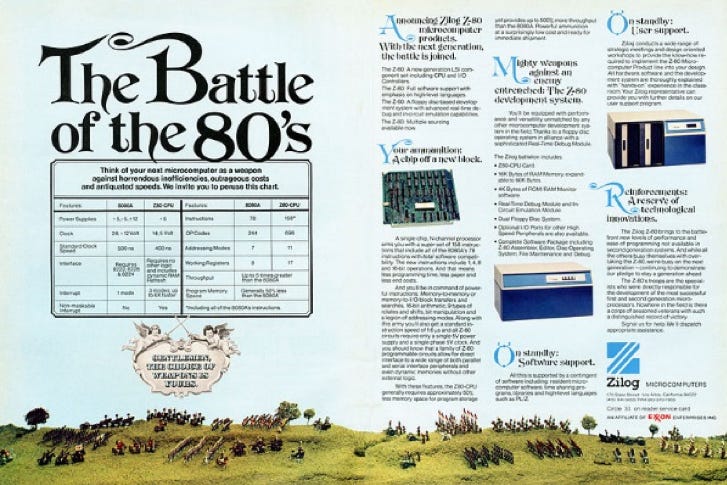

A few days later, a manager from Exxon called to let them know they planned to invest half a million dollars to get them started. Thus Zilog was born. It means the latest in electronics—‘Z’ the final letter of the Latin alphabet, ‘I’ for Integrated, ‘log’ is logic.

Z80 became the most famous microprocessor, the first to pave the way for Very Large Scale Integration, very high density integration electronics (Vlsi.) In just six years the company had 1,400 employees and a sales volume of more than 70 billion lire.

But Exxon was a control freak—no flexibility.

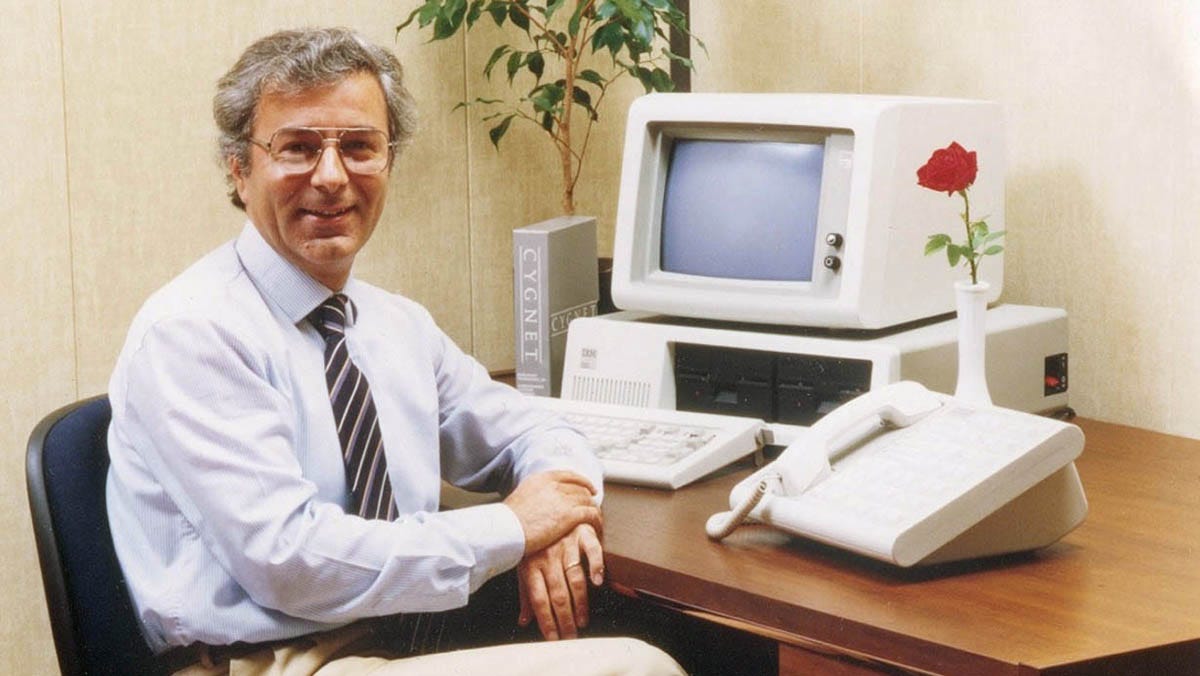

He left Zelig in 1981 to found another industry with a group of friends. It was smaller, more agile, but no less aggressive than the first. Cygnet Technologies (the technologies of the little swan) developed a new system of graphic and vocal communications in less than two years.

The invention won the award for the best electronic creation of the year at the international exhibition of new electronic products in San Francisco. The system allowed for the use of a screen to send messages, and the device to make (or schedule) calls simultaneously.

‘Desk-to-desk teleconference’ was born. Connected to the computer, the Faggin ‘smart phone’ made the dream of many managers and technologists come true—no wasted travel time, and the ability to continue work while answering a phone call.

But the new system had even more capabilities—it allowed to send and receive e-mail during low peak, lower cost hours. The electronic calendar could automatically set and cancel appointments, call up to 400 numbers and any database from the computer.

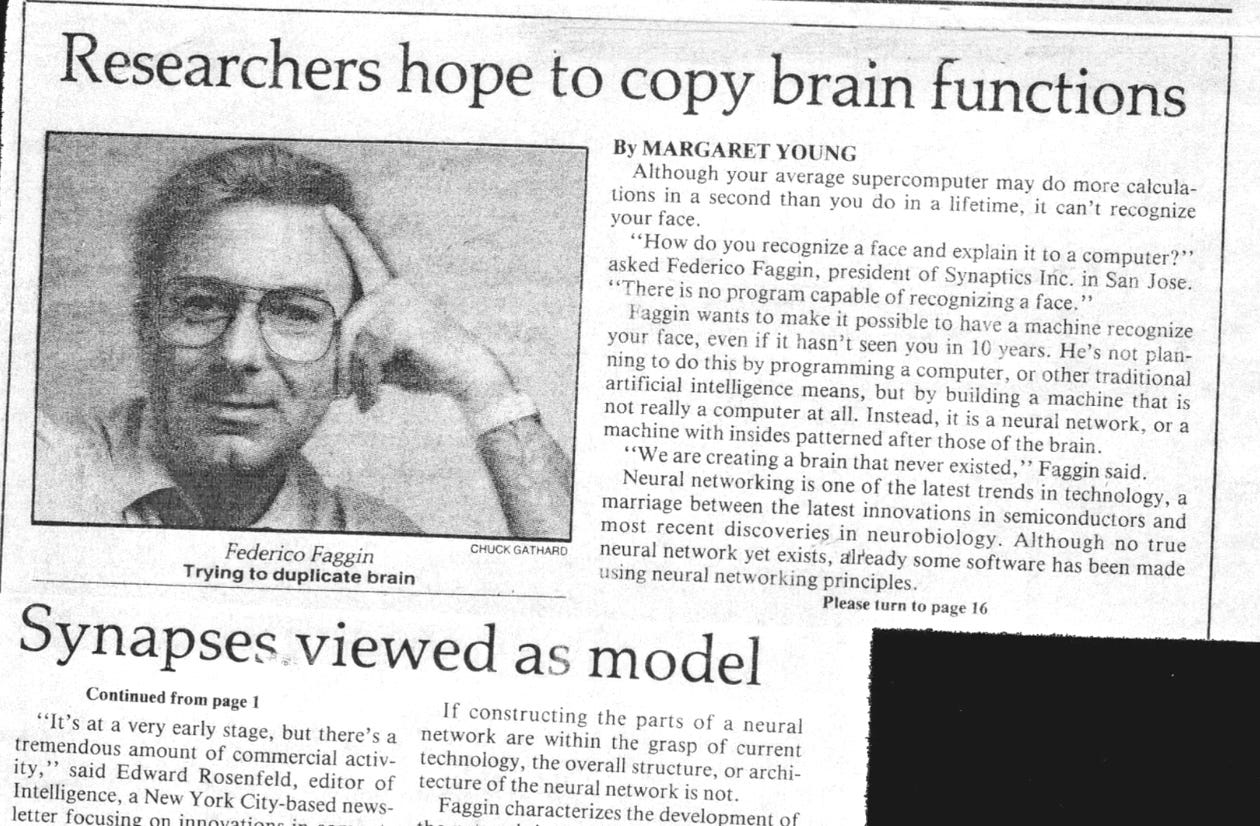

In 1986, Faggin founded Synaptics to work on the creation of neuronetworks. He then asked Carver Mead who was working on sensor chips to join and the company took off. The idea was to create computers that learn.

At the time, the entire artificial intelligence (AI) community was thinking that neuronetworks was a bad idea. In fact, we now know that they were the structure that saved the day in AI.

However, they could not solve the entire problem. The hardware was fine, but they could not find an overall architecture that worked. So they set out to do other things with the technology—hence the invention of the touchpad and the touch screen.

The company became very successful. Bill Gates is said to have declared that without Faggin, Silicon Valley would have remained just a valley.

But it was in that company that Faggin felt a sense of unhappiness. In the books he was studying on neuroscience and biology he also noted that there was no mention of consciousness.

So his question then became, ‘could I make a conscious computer?’ Based on the understanding that ‘consciousness comes from the brain, and the brain is like a computer.’

But there was no way Faggin could produce sensations and feelings, which is the way consciousness allows us to have an experience.

In fact, the idea that consciousness emerges from the brain because it’s made of matter is simply wrong.

The boundary between quantum physics, spirituality, and philosophy

That was an intense two lives—the first half of his work focused on computing. His success also showed him the absolute impossibility of making a computer conscious. Faggin’s second two lives begin in 1990.

“We want to know ourselves, and that’s the deepest thing we want, so why not start there to describe the universe.”