A puzzling world drives us to dig deeper

How the satisfaction of working on clues is a big clue to meaningful work.

Aimless online scrolling has dire consequences. Whenever I find myself in a creative dip, I know what to blame. The modern scroll is a non-activity, a symptom of boredom. Research proved over and over that scrolling has an adverse effect on mental health.

‘Look at all those accomplishments’ we start thinking. Because we compare our own indecision and stuckness to random posts. We forget many are just asides, comments with an image, opinions—which may not sit on solid (or high) ground.

A flood, an assault to the mind. Perhaps a hedge to the fear of a next or a new step. Like the sheet of ice on my walkway they beckon with shiny sparkle, but hide deception and a slippery slope of disillusionment.

On Value in Culture is a reader-supported guide to framing in narrative, language, books, value & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by paid subscription.

The pandemic accelerated and worsened a trend that was well on its way. Nearly 8 in 10 Brits admitted they spent meaningless time online. Social media had negative impact on the mental health of 3 out of 10 Brits—42 percent for 18-29 year olds.

As side effects of their desire to stay connected people took a hit on self-esteem (47 percent), got depression (40 percent), and had problems sleeping (39 percent.) We went online to seek inspiration, contact with others, information, and entertainment.

But not just any entertainment—we went in search of meaning, along with diversion. I talked to many who said they were reading again (a lot), learning something (a new language), dusting off old hobbies, and overall wanting to become better at something.

Crossword puzzles became a something. A ‘go-to’ for those who sought refuge from the news in Britain, Sweden, the Netherlands, Germany, and Italy. Crosswords have a long history in many cultures, one connected with troubled and uncertain times.

People do crosswords for many reasons—as a challenge to keep the mind active, to relax after a busy day or while commuting to work.

Overall crossword puzzles downloads increased by 28 percent (125 percent in Britain.) Education and tutorials were up as well. Interest in arts and culture at 58 percent beat science (54 percent) and news/politics (53 percent.) Home renovation was 48 percent.

When things don’t seem to go well around us, anything that engages the mind and emotions is useful. At 100, the modern crossword puzzle has been there before and during every major crisis humanity faced.

Playful beginnings

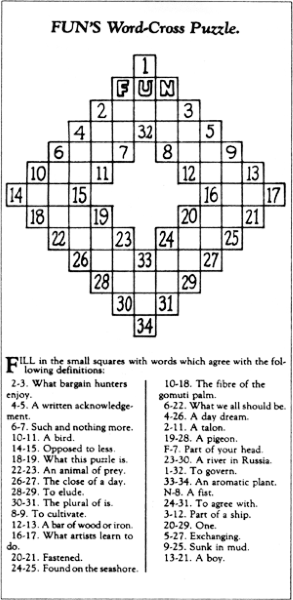

Arthur Wynne, a journalist from Liverpool, England created the first puzzle. Word games similar to crosswords (though not as intricate) were published in regional periodicals and children’s books in 19th century England.

Wynne emigrated to the United States in the 1890’s. The New York World published Wynne’s ‘Word-Cross’ on December 21, 1913. We were on the verge of a big war. Like all small things that can change everything, a typo turned the word from a cross into a crossword.

To note that the word ‘cross word puzzle’ first appeared in the Boston children’s magazine Our Young Folks. By 1873, word-based ‘double diamond puzzles’ began popping up in St. Nicholas, another popular children’s magazine.

Other newspapers picked up on the pastime in the early 1920s. England published its first one 11 years after Wynne’s—The Sunday Express broke new ground in the old country. Britain took to crosswords with gusto, and developed its own style.

Pearson’s magazine started the crossword craze. In 1922 Britain, soon dresses and shirts were made of crossword puzzle material—to this day, you can buy toilet rolls impressed with crosswords. Better than screens for concentration.

You’ll notice that American crosswords have fewer black boxes and all the letters intersect. So if you’re good with horizontal clues, you can solve vertical clues. It’s very efficient. Also, there are themes for definitions, trivia and wordplay.

British crosswords tend to be more cryptic—and thus more difficult. After experimenting with definitions and similes, The Telegraph published the first cryptic crossword on July 30, 1925.

By the 1930s cryptic crosswords had become more sophisticated in design—clues can be full or partial anagrams, double meanings and clues leading to further words.

“a cryptic crossword because each clue contains two parts. One part of the clue is straight, mimicking a standard American puzzle's clues. The other part can be straight as well, but is usually cryptic, meaning that it usually involves some form of wordplay. This often comes in the form of a rebus, reversal, anagram, homophone, beheadment/curtailment, or perhaps a combination of these! (That list is certainly not exhaustive.) What's more, the solver is not informed which part of the clue is straight and which part is cryptic, leading to a tougher solve.”

Neville Fogarty, crossword puzzle writer

The New York Times called crosswords a “sinful waste”

Meanwhile in America crosswords became so popular that Simon & Schuster published the first book of crossword puzzles. Called The Cross Word Puzzle Book, it contained a compilation of crosswords from the New York World.

The idea came to Richard Simon and M. Lincoln Schuster in 1924 to honor Simon’s puzzle-loving aunt. Due to the collection’s nonliterary format, they printed only 3,600 copies and included a pencil, but not the publisher’s name.

The book’s first run ran out quickly. And soon Simon & Schuster was reprinting. More than 100,000 copies sold. In a marketing move, the publisher started the Amateur Cross Word Puzzle League of America. The league began to create rules, like ‘all over interlock,’ that is no part of the grid could be cut off from the black squares.

But not every publication embraced the new pastime. The Gray Lady once labeled crosswords “a sinful waste… [solvers] get nothing out of it except a primitive sort of mental exercise.” As countless publications began including crosswords throughout the 1920s and ’30s, the The New York Times remained one of the only major metropolitan newspapers without a crossword puzzle. Until 1942.

Just months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Times brought in Margaret Farrar to serve as its first official crossword editor. The paper saw these entertaining puzzles as a necessary distraction to help readers weather the increasingly bleak World War II news stories coming from Europe.

Eleven days after Pearl Harbor, Eester Markel, then Sunday editor for The New York Times, sent a memo to the publisher, Arthur Hays Sulzberger.

“We ought to proceed with the puzzle, especially in view of the fact it is possible there will now be bleak blackout hours—or if not that, then certainly a need for relaxation of some kind or other.”

Eester Markel

Farrar had been editor at Simon & Shuster’s wildly successful crosswords series.

“I don’t think I have to sell you on the increased demand for this type of pastime in an increasingly worried world. You can’t think of your troubles while solving a crossword.”

Margaret Petherbridge Farrar

By 1950, the paper began running a crossword puzzle daily. Farrar remained the crossword editor until 1969 and established many of the regulations that have become industry standards.

Once it got in the game, The New York Times began to elevate the format and clues. In 2006, a documentary about then editor Will Shortz came out. Shortz had created a one-of-a-kind college major at Indiana University—’enigmatology’ or the scientific study of puzzles. He’s the sole graduate with that degree in 1974.

Wordplay, the documentary, was a love letter to the die-hard puzzle solvers who attend Shortz’s American Crossword Puzzle Tournament (founded in 1978)—with appearances by celebrities like Bill Clinton and Jon Stewart.

Suddenly crossword puzzles were cool in America.

Britain takes puzzles seriously

Menawhile, on the other side of the pond, readers started writing to The Daily Telegraph to share their speeds at solving the cryptic crossword. Finally, on 3 December 1941, the paper took up the challenge. They ran a competition—who can beat 12 minutes to solve a puzzle?

25 competitors were invited to the newsroom to test their speeds. The first completed the puzzle in 6 minutes 3.5 seconds (but was disqualified as he spelled a word incorrectly.) The winner took 7 minutes 57.5 seconds. The reward was a cigarette lighter.

After that, the War Office started to contact competitors. They felt their skills would be useful as cryptographers for code-breaking work at Bletchley Park. Codes to break were an all-consuming worry.

So much so that some feared crosswords were being used to convey secrets. MI5, the British intelligence service, started noticing the use of certain words in The Daily Telegraph. World War II was raging, D-Day was in the future.

Was Leonard Dawe, then crossword editor at the paper, communicating secretly with Nazi Germany through clues and answers in his puzzles?

On August 18, 1942, the clue ‘French port (6)’ appeared in the paper’s crossword. The answer was ‘DIEPPE,’ the site of a failed raid the Allied forces launched a day later. It was a fluke, a coincidence—the clue, not the loss, that hurt.

Dawe came under scrutiny yet again two years later.

The date of Allied invasion of Normandy was drawing near. On May 2, 1944, the answer ‘UTAH’ appeared in Dawe’s puzzle. Other answers such as ‘OMAHA,’ ‘OVERLORD,’ and ‘NEPTUNE’ popped up shortly after.

They were all D-Day code names.

Dawe was cleared again.

“They turned me inside out. Then they went to Bury St. Edmunds where my senior colleague Melville Jones [the Telegraph‘s other crossword compiler] was living. They put him through the grill as well. But in the end they eventually decided not to shoot us after all. Had D-Day failed, I suppose they might have changed their minds.”

Leonard Dawe, BBC interview, 1958

Ronald French was a student when the Strand School was moved from London to Effingham, Surrey after the Blitz started. He came clean and revealed the truth about the incident after the Daily Telegraph told the story of the crosswords getting attention from MI5 on the 40th anniversary of D-Day in 1984.

French had heard the words from Canadian and American soldiers at the base where he and other students spent all their time.

“Soon after D-Day, Dawe sent for me and asked me point blank where I had gotten those words from. I told him all I knew. Then he asked to see my notebooks. When he opened them, Dawe was horrified. Dawe screamed at me and said that my books must be burnt at once. I have never seen anyone so angry in my life. I was really scared, terrified of imprisonment. Mr. Dawe gave me a stern lecture about national security and made me swear that I would tell no one about the matter. He was very insistent on total secrecy. He made me swear on the Bible I would tell no one about it. I have kept to that oath until now.”

Ronald French

Something indeed was happening. The editor had been accepting crossword suggestions from his students. The students, in turn, hung out at a nearby soldiers camp during recess—they overheard the code words.

Italy makes crosswords useful

Giorgio is 28 when he decides to leave his Sardinian family of landowners and all his friends to seduce the beautiful Ida. Ida is a Viennese who lives in Milan. To woo her, he moved to the city.

Giorgio’s father—a pioneer of agricultural mechanization in Sardinia—suspected his eldest son also wanted to escape a generational transition. In response to the move, he cut off his financial support, leaving Giorgio penniless.

It will be the Austrian magazine that Ida always has in her hand, Das Rätsel (the enigma), that will give Giorgio Sisini the idea to earn a living. He worked on his idea while his sisters, secretly from their father, send him money to have something to live on.

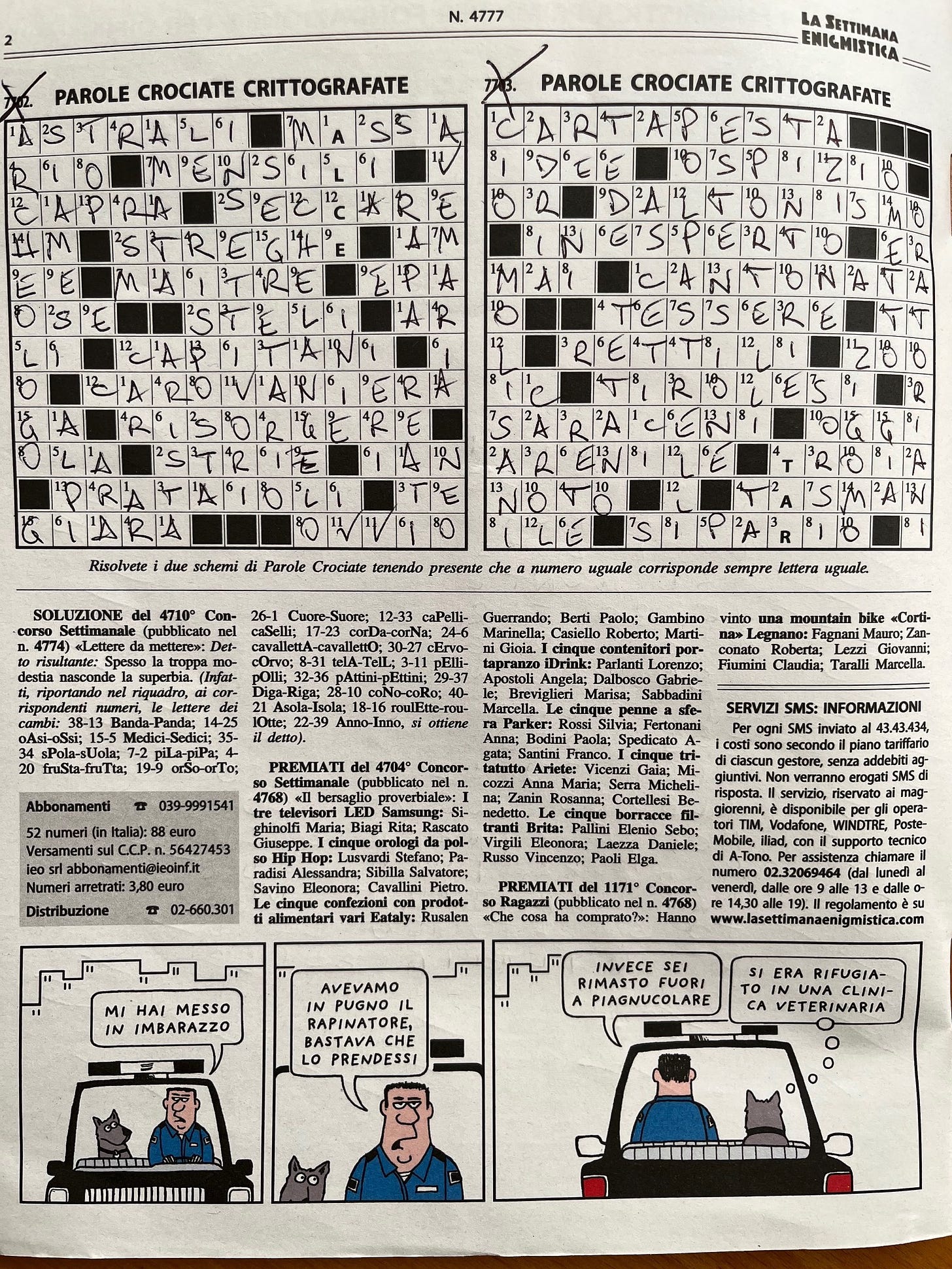

The publication La Settimana Enigmistica was born in a rented two-room apartment where the couple lived. Father of the phrase ‘parole crociate,’ Giorgio took care of everything, from content to distribution.

He released the first issue on January 23, 1932—a palindrome date (23-1-32 in Italy.) Paced by an uninterrupted weekly release (only issues 607 in 1943 and 694 in 1945 were postponed by a few weeks), the magazine marks Italian customs and culture.

Crosswords helped reduce illiteracy from 20 percent in 1930 to today’s 0.6 percent.

The winning formula of the Sisini, now led by the founder’s grandson, is an almost unchanged format. From the very recognizable cover where they alternate female (odd numbers) and male (even numbers) faces.

‘The comparison,’ ‘Sharpen your sight,’ ‘Susi’ or the ‘Crosswords Without a Pattern’ crossed generations with the authors. First of all Piero Bartezzaghi, the greatest puzzler of the Italian 20th century, whose legacy was taken up by his son Alessandro.

The publisher’s secrecy borders on the maniacal. The editorial staff has been at 10 Piazza Cinque Giornate in Milan since time immemorial, but nothing is written on the intercom. The family doesn’t give interviews, nor allows to be photographed.

Perhaps it’s because the company with a turnover of €50 ($54.39) million earns so much, it’s never succumbed to the lure of advertising, despite the mind-boggling offers.

While I’ve tried crosswords in America, they don’t feel as satisfying as solving those in La Settimana Enigmistica. Whenever I’m in Italy, I buy a new issue every Thursday to bring home. It’s one of the ways I stay in touch with popular cultural and language.

A test of wits

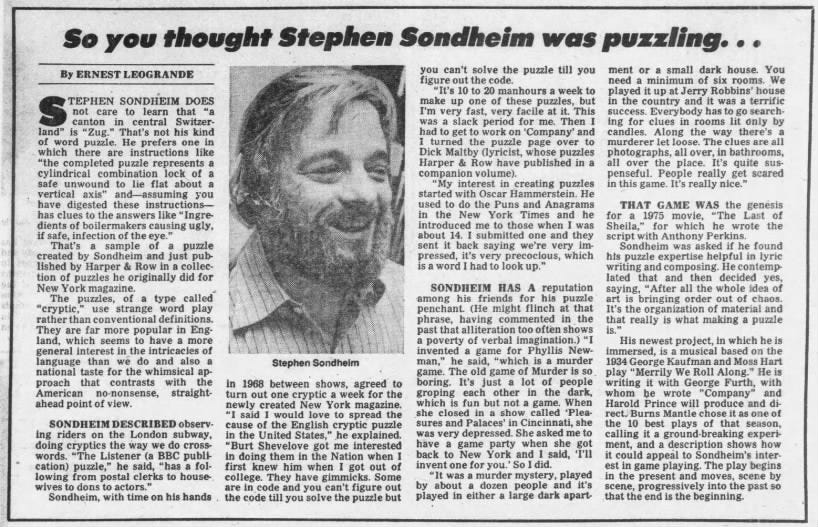

To shake off the yoke of efficiency, in 1968, lyricist Stephen Sondheim introduced American readers to ‘real’ crossword puzzles—the cryptic crosswords—in New York Magazine. Sondheim argued that American crosswords required ‘tirelessly esoteric knowledge.’

Their preferable British counterparts instead “have many characteristics of a literary manner: cleverness, humor, even a pseudo-aphoristic grace.” It’s deeply satisfying to solve this kind of puzzle. You feel more accomplished responding to the clues.

Different puzzle writers have different cryptic styles. You can get to know them and their styles over time. It’s like having a conversation with a favorite author. There’s more context because we do tend to gravitate to what we know and enjoy.

I mentioned Bartezzaghi above. His crosswords were always challenging—toward the end of the booklet. But solving one made me happy. A good clue can give you the catharsis of a solution.

A good clue is layered with meaning. And you are off to a quest.

Out of love for the form, Sondheim ended up writing cryptic crosswords for New York magazine for a year and a half. He left the gig in 1969 to focus his efforts on his new musical, Company.

Sondheim’s musicals can feel like puzzle palaces, and to enter one is “to look at the unsolvable puzzle of life, and find endless riches within it.”

Isaac Butler, Sondheim obituary, Slate

In 1993, a testament to its popularity, The New York Times started posting its daily crossword puzzles online. Anyone stuck bored at home during the pandemic could catch up with the archives for a test of wits.

Today, The Guardian Crosswords is Britain’s most popular puzzle. Both quick and cryptic versions are online (and free.) The publication’s crossword blog “looks at the smartest and wittiest clues from all the cryptics.” A recent example for beginners:

20d Note from singer on the radio (6)

[ wordplay: soundalike (‘on the radio’) of a kind of singer ]

[ definition: slang for a banknote ]If someone with the range of Luciano Pavarotti were described on the radio, it would sound the same as our answer, TENNER.

The Times Crosswords remains an iconic part of British culture with a tradition of anonymity. Available to subscribers, the publication has a daily cryptic crossword (Monday to Saturday), and prize crosswords on Saturday. A ‘Times for the Times’ independent blog offers clues and comments on the crosswords.

The London Times cryptics were a favorite of American musical theater playwright, lyricist, librettist, and director Burt Shevelove. In New York, Shevelove and Sondheim bonded over crosswords and later worked together on ‘A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum,’ nominated for a Laurence Olivier award in 2000.

Both lyricists fell in love with the very intricate puzzles in The Listener, a weekly magazine published by the BBC. “Of all the publications, The Listener had the most elegant, complicated, devious, interesting puzzles,” said Sondheim.

“Sondheim’s earliest Listener puzzles are simply cut out from the magazine and left unsolved,” according to Will Shortz who met Sondheim in the 1980s. But he kept the puzzles anyway, to solve later. Which he did with a crossword from 1956.

By then, Sondheim began writing the lyrics for West Side Story, a collaboration with Leonard Bernstein, also a lover of crosswords. Puzzles became part of the creative process for the two artists.

“I’d grab a copy on my way to work on West Side Story, and I got Leonard Bernstein hooked. Thursday afternoons no work got done on West Side Story. We were doing the puzzle.”

Stephen Sondheim

I can understand how that happens. The creative process is hard.

I got hooked to crosswords during difficult periods in my life. Puzzles and crime fiction—books by women authors and British series—are my refuge, because I can think my way through a solution in both. Better clues make me a better thinker.

But I agree with Sondheim, “One of the great things about crossword puzzles is, there’s a solution. And that’s unfortunately not true of all the puzzles in life.” Eventually, we all need to re-emerge into the uncertainty and create our way out of something.

Sondheim and Bernstein investigated reality through lyrics. Value in culture is my art, a step beyond the refuge of crosswords, the work I do to ask better questions of the clues in life.

References:

‘Britons have downloaded 125 per cent more online crosswords since coronavirus lockdown started,’ Soundwealth (May 2020)

‘Wellness impacted by meaningless scrolling during coronavirus lockdown,’ Readly (April 2020)

‘Brief History of Crossword Puzzles,’ George Eliot, American Crossword Puzzle Tournament

‘A History of the Crossword Puzzle in 5 Clues,’ Google Arts & Culture

Raphel, Adrienne, Thinking Inside the Box: Adventures with Crosswords and the Puzzling People Who Can’t Live Without Them (Penguin Books, 2021)

‘The Differences Between an American Crossword and a British Crossword,’ My Crossword Maker (2018)

‘The Cryptic Crossword Puzzle,’ Neville Fogarty, The New Yorker

‘The History Of The New York Times Crossword Puzzle,’ Dictionary.com (2018)

‘These Crossword Clues Nearly Gave Away The D-Day Invasion,’ Jeremy Bender, Business Insider (2014)

‘Crossword Alarm: The Puzzle That Nearly Stopped D-Day,’ Dejan Milivojevic, War History online (2019)

‘Wordplay,’ an in-depth look at The New York Times' long-time crossword puzzle editor Will Shortz and his loyal fan base.

Alessandro Scaglione on the history of ‘La Settimana Enigmistica’

‘How to Do a Real Crossword Puzzle,’ Stephen Sondheim, New York Magazine (1968)

‘Stephen Sondheim Didn’t Just Change Musicals. He Changed Crosswords.’ Ben Zimmer, Slate (2021)

‘How the Crossword Became an American Pastime,’ Deb Amlen, Smithsonian (2019)

A Times for the Times blog

‘A Funny Thing Happened to Stephen Sondheim,’ Norman Lebrecht, The Lebrecht Weekly (2004)